This article was originally published in Dutch on MUNCHIES NL.

More often than not, chefs are bone tired. But ask them about their favorite knives and, without exception, their faces light up. It’s almost impossible to describe the special bond that exists between chef and knife, but we’ll try anyway. Today, Belgian knifesmith Dimitri Turcott Smekens shares the story of his unique introduction to his craft.

Videos by VICE

I meet Turcott at his studio in Zoersel, a borough of Antwerp, Belgium. For the past two years, the knifesmith has been working in an old barn right next to his house, which is surrounded by open fields. People passing by would never guess that inside of this building, instead of sheep and haystacks, there is steel and wood, the resources of a man who figured out how to make knives all by himself.

All photos by Raymond van Mil.

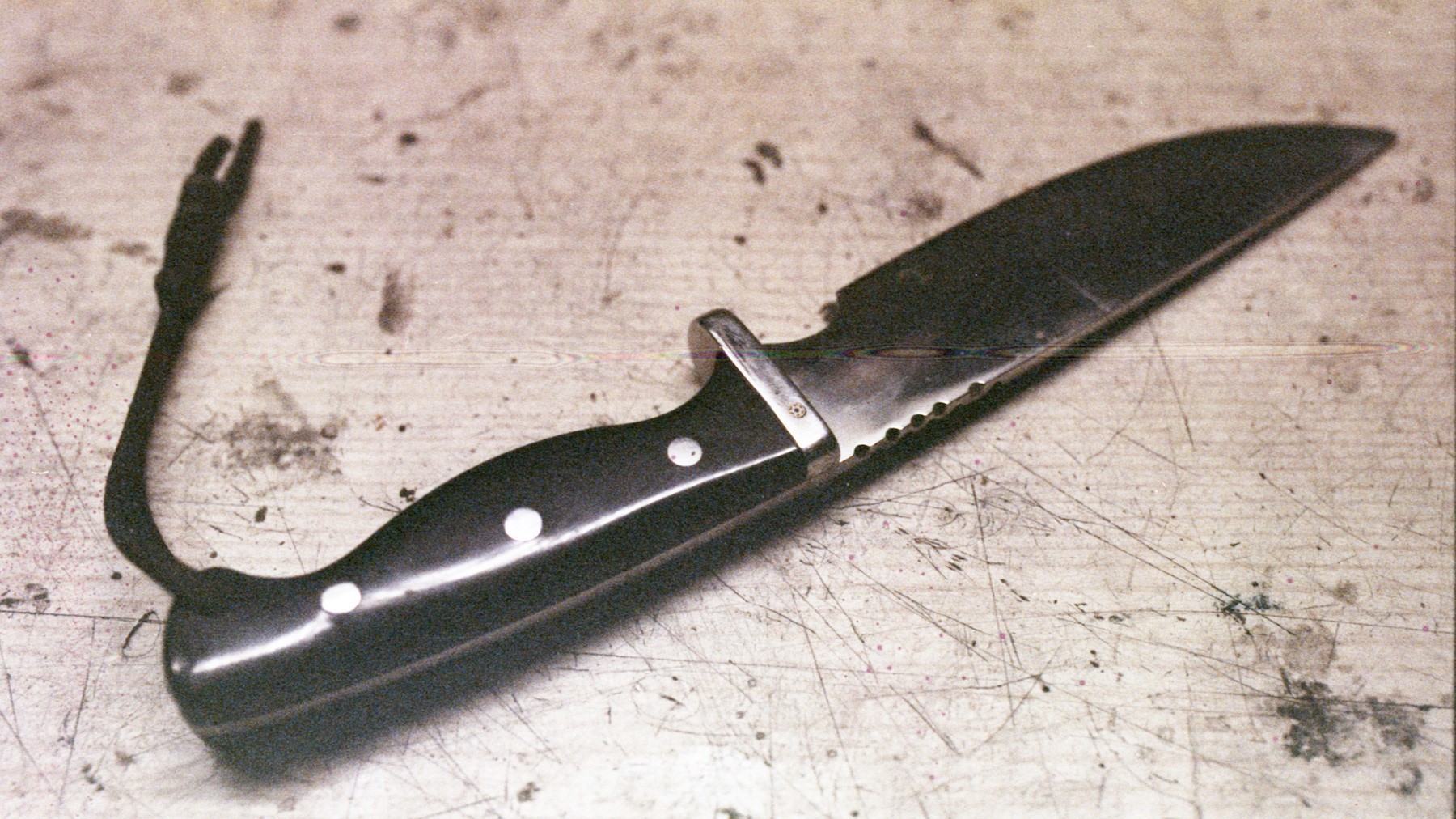

When I arrive, Turcott has already put his knives out on display. I pick up the heaviest and biggest knife and inquire about its purpose. “This is a showpiece, a knife mostly used for hunting. It has a round protuberance, which protects your hand from sliding down to the blade. There’s also a gap close to the blade, where you can rest your finger for extra stability, so you’re in full control while you’re cutting”, he explains.

Turcott isn’t a typical knifesmith. He doesn’t practice a craft that has been passed on from older generations, and he doesn’t work with any secret recipes, either. “I was classically trained [in music], and then got a job as an audio engineer,” he says. “I do that [work] to this day. Every summer I work at music festivals, but when the festival season is over, I do a lot of other things. I’ve always been big on the outdoors, I do a lot of trekking, I hunt. I have a business that organizes trips into the wilderness, for which I travel together with a friend in the most self-sufficient way possible: camping in the jungle or desert, and hunting.”

During those survival trips, the importance of a good knife became clear. “I was looking for a good knife, but the one I wanted was very expensive. So I thought: why don’t I try to make my own knives?

READ MORE: This Chef Makes Beautiful Knives Out of 7,000-Year-Old Oak

“I have a very obsessive personality”, he continues. “When I want something, I really go for it. Knife-making is a dying craft, so I read old books, did a lot of online research, and visited many knifemakers all over the world.” In every new country he visits, Turcott looks for a local blacksmith. “In Borneo, I searched for days, until I ended up in a tiny village with all of these knifesmiths. I bought a parang (a type of machete) there and used my hands and feet to talk [to the blacksmith] about his materials. That knife was made out of leaf springs from trucks, and he made it using less resources than we have here. Very impressive!”

Meanwhile, Turcott keeps 60 knives from all over the world in his house. “This hobby got so out of hand, I go looking for resources when I’m traveling. From India, for instance, I brought a little over 15 pounds of steel. From other countries, I bring six or seven other pieces of material, from hatchets to machetes. They are my study materials. At customs, they often stop me, but I’m not doing anything illegal. I don’t really understand that people associate knives with danger. It doesn’t have to be a lethal weapon. People handle knives on a daily basis to cut sandwiches and open cardboard boxes, right?”

Turcott made his first knife 10 years ago. “What surprised me the most is the difference between the second and third knife I made. The second was so good, I could hardly believe I had made it. To this day, that knife is displayed on my mantle; it serves as a reminder of the moment I decided to continue doing this, because it turned out I really had a knack for it.”

At that time, he didn’t have any equipment to work with, so it took him six months to figure out how to properly finish the knife. He spent all of his spare time polishing the knife with a file. “Have you ever tried to polish steel using a file? I can tell you one thing: it’s a lot of work.”

Turcott started with some black coal, a piece of old train track he used as an anvil, a hammer, and a small forge. “I started out by hitting pieces of warm metal and made a lot of mistakes during this DIY-exploring phase. With every attempt, I gained new insights, and it’s due to my mistakes that I really learned how to do this well.”

He took his first line of knives to De Invasie (‘the invasion’), a convention for young designers. “There, I sold almost all of my knives and I got many positive responses from the people who had bought them.” These days, he makes knives for chefs in a workspace filled with professional equipment.

“I’m increasingly focused on the hospitality business. Chefs come to my workspace and can choose what kind of wood they would like their handle to made of, and help me to determine the shape of the knife. After that, I get to work. Recently, a hotel manager ordered a knife for a female chef he has a crush on, who works in a restaurant in Monaco. He asked me to create a girly design and he sent it to her.”

READ MORE: Inside the Secret Blacksmith Shop That Crafts Knives for Michelin-Starred Restaurants

“Because it’s not easy to make a chef’s knife, there is a bit of a wait. Depending on the size of the knife and the complexity of its structure, it takes me anywhere between four days to two weeks.”

Turcott starts a fire and shows me how he manipulates a piece of metal. It’s been polished very roughly, and once the metal becomes hot enough to turn red, he takes it out of the flames so he can pound on it. Once the orange hue of the heat fades, he sticks it back in the fire. “You easily end up a few hours pounding the metal”, he says. “Ultimately, it becomes smaller, until it’s very thin. Chef’s knives are thinner than survival knives, which makes them a lot more fragile. The secret is temperature control, so you don’t burn the steel while you’re working. In a few seconds, you can potentially ruin a week’s worth of work.”

Different kinds of steel, wood, and leather litter his workspace. “The most fascinating aspect of making knives is starting out with raw materials and making a beautiful and useful tool out of them. I don’t do anything with computers [in here]. That’s a breath of fresh air, after I’ve spent a lot of hours behind a screen in a dark room while working in the music industry.”

It isn’t always easy to acquire the right materials, especially because Turcott focuses on sustainability as much as he possibly can. “I mostly look for materials I have a personal affinity with. I use the horn of a water buffalo, for instance, which is also used to make traditional Japanese knives. But recently I discovered that the horns of a bull are also great to work with. They look very good once polished and people just throw them away. Why would the horn of a bull be inferior?”

According to Turcott, 50 percent of a knifesmith’s time is spent searching for the right metal and good wood. “Many times, you have to look for your materials abroad. It’s still a niche; you don’t find a store with knife-making materials on every corner,” he says. “Sometimes you get lucky. Recently, a friend gave me parts of an old staircase because his wife thought the wood was too dark. Turns out it was Wenge, a rare type of tropical wood from Africa. Amazing! Now I have so much Wenge, it’ll last me at least another year.”

At the moment, Turcott is working on 20 knives for a restaurant that ordered a slightly bigger version of the Kiridashi knife for guests to use as steak knives. “People say I have a specific style, but I wouldn’t know what to call it. I just do what I want to do and if I feel inspired, I make set after set. It could be five chef’s knives or five hunting knives. My designs are constantly evolving and are sort of centered around whatever my current obsession is.”

Turcott claims not to have a secret recipe, though he doesn’t spill all of his secrets during the workshops he teaches in his barn. “I have a lot of fun passing on my knowledge [to other people]. When I started out, it would have been nice to have someone around to help me, but I’m not going to give everything away. People need to earn it a little bit. If they ask the right questions, they get the right answers.”