You know you’re in the right place when there’s only one thing on the menu. With the Bánh Mì Queen, you’re in good hands.

Nguyễn Thị Lộc, 79, makes the best bánh mì in Hoi An—and probably all of Vietnam. When translated to English, bánh mì means “bread,” but it’s also a general term for Vietnamese sandwiches. Lộc’s bánh mì attracts tourists to Hoi An, a beach city in central Vietnam that has placid riverside cafes, a lantern market, and a party scene that hints at too much Chinese money and influence.

Videos by VICE

Lộc’s shop is 15 minutes north of the Thu Bon river, tucked away in a less touristy part of the city. The waifish woman has had her storefront for 30 years, and has been selling street food for almost 50. It’s a simple place with four tables behind her sandwich stand, which is perched just off the street at the forefront of the shop.

Aside from being called the Bánh Mí Queen, Lộc is sometimes called Madam Khanh, but it’s a misnomer that uses her husband’s name, which she did not take. She has nonetheless embraced it: her awning reads, “MADAM KHANH THE BANH MI QUEEN.” She’s a street food icon and welcomes the hype that comes with it.

From 7 AM to 7 PM, she makes up to 200 sandwiches, and the first is generally the same as the last: pâté, pork char siu, sausage, fried egg, homemade pickles, papaya, carrots, parsley, chili sauce, soy sauce, and her secret sauce. The result is a well-balanced sandwich that’s sweet and salty, spicy but basic, crunchy yet creamy.

Street food runs in Lộc’s blood. At 20 years old, she got her first job selling sweet bean soup, which isn’t a soup at all by Western standards. It looks something like an eyeball smoothie—gelatinous, opaque, served on ice—but it’s a surprisingly sweet and refreshing drink. During the American war, she was restricted to selling from home, though the conflict steered relatively clear of Hoi An. After the war, she carried her soup on a bamboo stick with baskets on either side. And finally, she settled back at her house and started her bánh mì business in 1985.

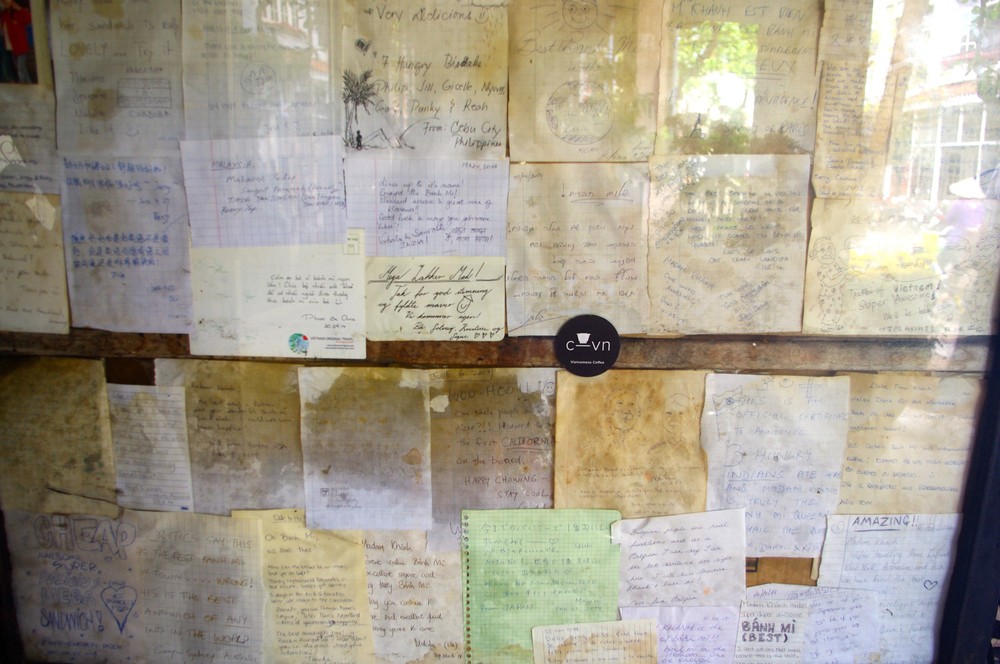

She strives to make an impression upon eaters and create an unforgettable sandwich. Nothing pleases her more than receiving letters from tourists expressing how much they enjoyed her bánh mì. She displays such letters in a glass case just behind where she stands. And she admitted she feels sad when she’s forgotten by tourists, passed over as just another meal.

“I’m careful with every step of the process to make the perfect sandwich. Every step—slicing the meat, picking the vegetables, cooking the eggs—to make the tourist feel happy,” she said via translator Nguyên Trần Trung.

Her perfectionist approach to street food has made her a steward of the street foodie movement. When travelling in Vietnam, you never need to step foot in a restaurant; the street food is cheaper and better. Because of its popularity, the government has mandated measures of cleanliness to ensure a steady flow of tourists, although those efforts sometimes fall short. Still, Vietnamese food has emerged on the international radar, and the Bánh Mì Queen isn’t just riding the waves: she’s making them.

She’s up every day with her husband Bùi Văn Khánh to purchase and prepare the day’s ingredients. After a quick trip to the local market, she’s back in time to receive the baguettes, one of the few cultural holdovers from French colonialism for which the Vietnamese seem thankful. The bread is baked in Hoi An every morning and is the perfect mix of crispy on the outside and airy on the inside.

Once the store opens, she waits at her stand, watching scooters buzz by on the street. Her sister-in-law and daughter serve clients that choose to stay, and her husband wanders in and out of the shop with his hands folded behind his back, never saying a word. In the afternoon, her granddaughter joins them, giggling and chatting with locals.

The sandwich—like everything in Vietnam—has two prices. There’s the local price of 8,000 to 10,000 Vietnamese dong (40 to 50 cents) and the foreigner price of 20,000 VND ($1). If a tourist is smart enough to haggle with her, Lộc is happy to concede the lower price.

She takes great pleasure piling each sandwich with ingredients. Then she hands the customer the sandwich in a bag: It’s so juicy, it will drip on your clothes.

“One hundred percent of the customers eat my sandwich and give it thumbs up—no thumbs down,” Lộc said with a modest smile.

The sandwich love isn’t lost on her daughter Bùi Thị Nga, whom Lộc expects to take over the business once she retires. But it’s definitely still Lộc’s operation.

“I sometimes want my mother to rest, but I fear that if she stops, she will fall ill,” Nga said. “She has to do something to keep the body motivated.”

Lộc emphasized the idea, too. Bánh mì production keeps the Bánh Mì Queen alive.

There are countless bánh mì stands in the city, but the locals and tourists adore her, and Lộc doesn’t sweat the competition. People know her name, she reasoned, and her reputation precedes her. She’s a street food icon, and eating her banh mì is a Vietnamese tourist’s rite of passage.

This post previously appeared on MUNCHIES in September, 2015.