This article originally appeared on Noisey UK.

Like most people, music was always on in my house as a child, but with a small difference: My father was a vinyl collector. Not in the “I buy two or three records a week” way, more in the “I have 13 fucked turntables piled up at my backdoor and you can’t get upstairs” way.

Videos by VICE

From eating at a three-legged table propped up by a stack of country and western albums, turning up to fancy dress parties as a toddler wearing records cellotaped together, or the feeling of frightened amazement as my dad danced around the house with a seven-inch single he’d found that meant he could pay the mortgage that month, vinyl was a constant.

With filled boxes lining the stairs, whoever came into our home accepted my dad’s obsession and inevitably took some part of it away with them. What always astonished me, however, was how he saw his relationship with vinyl as completely mild. My mom would be laughing, measuring the extra yard of the living room the boxes were taking up like a crime scene, and he would palm it off, shake his head and give a PTSD-sounding, “If you’d seen what I’ve seen.” We nodded, but none of us ever took it seriously. In fact, I didn’t really give it a second thought until recently, when I heard about Brian.

Known by every charity shop owner from the Black Country to Warwickshire, I met Brian in the same way everybody does: in a hospice, flicking through albums. We got talking, and I quickly learned that this is the way he spends every day of his life. After a lot of back-and-forth, answerphone messages and last minute change-of-plans, he let me visit and see his collection. A man who has worked, breathed and—quite literally—lived on the format for the past five decades, he opened my eyes to a world I did not really know existed.

I decided to track down more Brians, finding some of the country’s most dedicated vinyl hoarders, in an effort to unpick the mysteries of a culture that predates Steve Jobs going through puberty, let alone the digital revolution. What I found was a bunch of characters you couldn’t write—Brian, Deepinder, and Paul—complex, inspiring and passionate folk with encyclopedic minds, who were truly infatuated, engrossed and sometimes overcome by their love for music. People who were making huge sacrifices—from broken hips to broken marriages—just to keep collecting. Here’s how I met some of the UK’s most obsessive vinyl hoarders…

BRIAN

I’m stood in front of a semi-detached house in the midst of suburban Britain. Two knocks and I’m greeted at the door by Brian – albeit tentatively—and I completely understand; I’m one of just five people to have been invited into this house over the past 20 years. Vinyl is orderly, but everywhere, stacks of it piled above my height. The ceiling is bowed, dipping in the middle, “because the room above us is filled from top to bottom, completely” but that’s no anomaly. Besides a precarious route to the downstairs toilet, this is the only room in his two-bedroom house that is useable. I use that word hesitantly in that, the windows are blocked and you can see your breath because sunlight is a bad thing for records and central heating is ten times worse. There is a clear view to a muted Antiques Roadshow from a two-seater sofa. One of its seats is, if you’re getting the theme, covered in vinyl. Brian offers up the free one, but I insist it is his and drop to the carpet.

Noisey: How did it all start?

Brian: I’ve got an older sister and when I was six years old we went into Shirley (Solihull) together to buy my first record with pocket money that I had saved. It was 1963, and it was a Joe Brown record. From that moment, I was hooked, immediately. You’ve either got [the bug] or you don’t. I was married for six years and my ex-wife didn’t like music at all. It didn’t mean anything to her. I thought we were great in every other way but I never learned why she didn’t have music in her life. Strange.

Can you describe your emotions when you see something that you want?

It means the world to me. I’ve been out of work for seven years, I’ve got no income coming in but I’ve been spending my savings. It’s dwindling though. I’m a single bloke, I’ve got no kids, I’ve got a few good friends in the record collecting realm, but I’ve got no extended family. I’ve got one sister, that’s it. Nobody to pass my records down to. But I’ll go out, every day, for a nice drive out in the car with some good music on. I’ll meet some nice people and every now and then I’ll drop in on some nice records. And it makes that day worth getting up for. I’ve had a phone call tonight from a charity shop in the Black Country who said they have had some records in, some of them are Elvis HMVs, can I come over? Now, I am sat here and—though I’m giving you my attention—all I can think about is that I can’t wait to get up tomorrow morning and drive over.

One of three jukeboxes within an arm’s reach of my seat on the carpet.

What’s do you think will be the consequences of all your collecting?

I don’t know. I’m 60, so I think I could sell a good proportion of them if push came to shove. I haven’t got computer skills so that’s one of the things that’s slowed me down, so maybe a shop. Have you seen High Fidelity?

Yeah.

Well, I like the idea of the fun you can have in a record shop, taking the piss out of the people who come in, decrying each other’s tastes; that’s a dream. I’ve always been a salesman so I know I can sell and would enjoy that. I used to be in the trade in the 80s working for a record label and a distribution company before the industry pulled the plug on vinyl.

How has collecting impacted on your personal life?

It’s become my lifestyle. It wasn’t always. Whether it’s the reason that I broke up with my wife or girlfriends, I don’t know anymore. But now it’s become what I get up to do, it’s everything to me. It would be very difficult to break out from it. Imagine I met a very nice lady now—I couldn’t invite her into my house. Well, I could, but she’d have to be a nutter like me to be happy to not have the heating on because there’s so many records that take precedence.

Rubber Souls; turned my head and counted 32 copies of the Beatles’ White Album – “And that’s not even all of them”.

Was it a sacrifice worth making?

I don’t see it as a sacrifice, because collecting is everything to me. Perhaps to the man in the street I have sacrificed. I’ve sacrificed the fact there’s a hole in the roof that drips water just behind you—somebody should’ve looked at it three years ago, but they can’t get in because there’s so much stuff in here. I’ve sacrificed the fact that I sit here in a coat in the one chair in the house I’m able to sit in. I’ve sacrificed the fact that I can’t go to Greece. I love Greece, I’d go in a heartbeat if I could, but the money’s in the collecting and I’d worry that I was missing out on records.

Would anything ever convince you to call it a day?

Probably health. I know I need a new hip—I’ve been putting off having one because you couldn’t get anybody in here to look after me for the aftercare. Something could easily happen that means I couldn’t go out every day, or I’d need care or a sanitary bathing system. I mean, I’ve got records in the bath for God’s sake. I’ve thought for a long time, “This is ridiculous, Brian.” But the truth is, I’ve been on my own for a long time and there’s nobody to tell me to stop.

DEEPINDER

Birmingham’s sanctuary for collectors’ is the Diskery, a shop that has been a reputable gateway drug for curious, enthusiastic musicians and listeners since the early 50s. “Where this place used to frown upon youngsters, we’ve noticed a lot coming in here over the past eight months,” the owners tell me. “We don’t stock modern music, but they’re still coming in. It’s like the house and dance 12-inches, we’ve stocked those for years and they’ve only just started shifting. If there is a resurgence, vinyl can owe it to that scene. They were the only labels pressing in the late-80s and 90s’.”

It’s no surprise that local collector Deepinder arranges to meet here. Opening up a tattered Reader’s Digest box, he starts fingering through its contents. A Led Zeppelin I, “worth £3,500 to £5,000”, a “£3,000” copy of Norman Haines’ Den of Iniquity, or any other of the ten treasures within, it’s a thing of beauty for the gathering collectors’ and me. Better yet, it’s just one of the “seventy or something of a similar value” that make up the jewels in the crown of the best progressive rock collection in the country.

Raised in Aston, an area renowned for its heightened crime rates and industry, Deepinder’s curiosity with vinyl was first sparked when he picked up an Arzachel album in 1978 for 10p. His obsession escalated, leading all the way to regular trips to the skip outside of EMI’s office in London for reasons I’ll let him tell you, or once to Battersea Power Station where he broke in to take a planning notice for his copy of Pink Floyd’s Animals. Adding these items of interest to a vinyl can make or break its value you see. As the years have gone by, items of interest have gotten harder to come by. It’s not unusual for Deepinder to chase executors of record label executives’ wills in search of phantom albums.

Noisey: How many records do you think you own, roughly?

Deepinder: Well, in 1985 I counted 2,000. I haven’t sold many, I’ve always added to it. So who knows, it could be something like 6,000 or 7,000. Then I have another 3,000 singles or more.

What do you think of the new vinyl buyer? Pilgrims of this “resurgence”—the middle income man in their mid-20s?

I’m sure that there’s some truth in that but one thing I have noticed is that there are way more young women going into shops and buying records. Collecting has always been a massively male-dominated area, but it would be great if more women could get involved. It would change the dynamic. Look behind you.

“I got my record player in September from Argos. I walk past the Diskery on my way to University every day and it’s dangerous. I’ve spent so much money and have about 50 records now, all second hand.”

“Well, she collects properly (on the left), but I’m buying this Otis Redding album even though I don’t have anything to play it on. God, I hope that doesn’t sound too hipster, but I just don’t want to be as modern as everybody else is.”

You told me you come from a working class, first generation immigrant family—did you ever get the feeling your interest in records swayed from what your family expected of you?

Yes, mainly from my mother because she felt it was an unnecessary diversion away from my studies. She once heard me playing “Madcap Laughs” by Syd Barrett but thought it was squeaky and rubbish.

Did she ever make you think about stopping?

No, I’ve never come to that sort of fork in the road that collectors’ who have a family to look after or so on have, where they have to think about getting rid of stuff. I’ve just carried on really, the same as I’ve always been, except I’ve taken it very seriously. Some of the major purchases I’ve made… I’ve paid £2,000 for an LP.

What was that?

Apple on Page One [An Apple a Day by British psychedelic band Apple, released on Page One Records in 1969]. I got that from the widow of a record executive four or five years ago. But I sold it, for £4,000—I regret it now. It’s one of those LPs you’ll never find again in that condition.

How has collecting impacted on your life?

Well, it does take over your life, really as picking it up is the best feeling in the world. It’s difficult to try and put into proportion other parts of your life in comparison with vinyl, because it’s so all-consuming. I don’t want to go anywhere because I think I’ll miss out on things.

Deepinder’s original Led Zeppelin I, worth £3,500-£5,000.

What do you think you’re missing out on?

A collection. These opportunities are getting rarer so you have to be able to turn on a sixpence—collecting has made me live in the moment. I remember when I was younger, 20 years ago, my sister showed me a clipping in the Guardian describing how the Lithuanian Frank Zappa fan club were erecting a monument to him. So I thought, “Bloody hell!” I borrowed some money off a friend, told my mother I was going to Leicester for a few days, and got a plane ticket to Lithuania to see it. I can still remember it intensely.

What’s the weirdest shit you’ve done for vinyl?

I do a lot of researching to try and speculate what auction houses or estates things that I want may show up in to get an edge, but I’m not sure really. I used to go down to London to look in EMI’s skip. I still have a lot of Pink Floyd files, and I also have a copy of Kate Bush’s original birth certificate that her parents submitted to EMI.

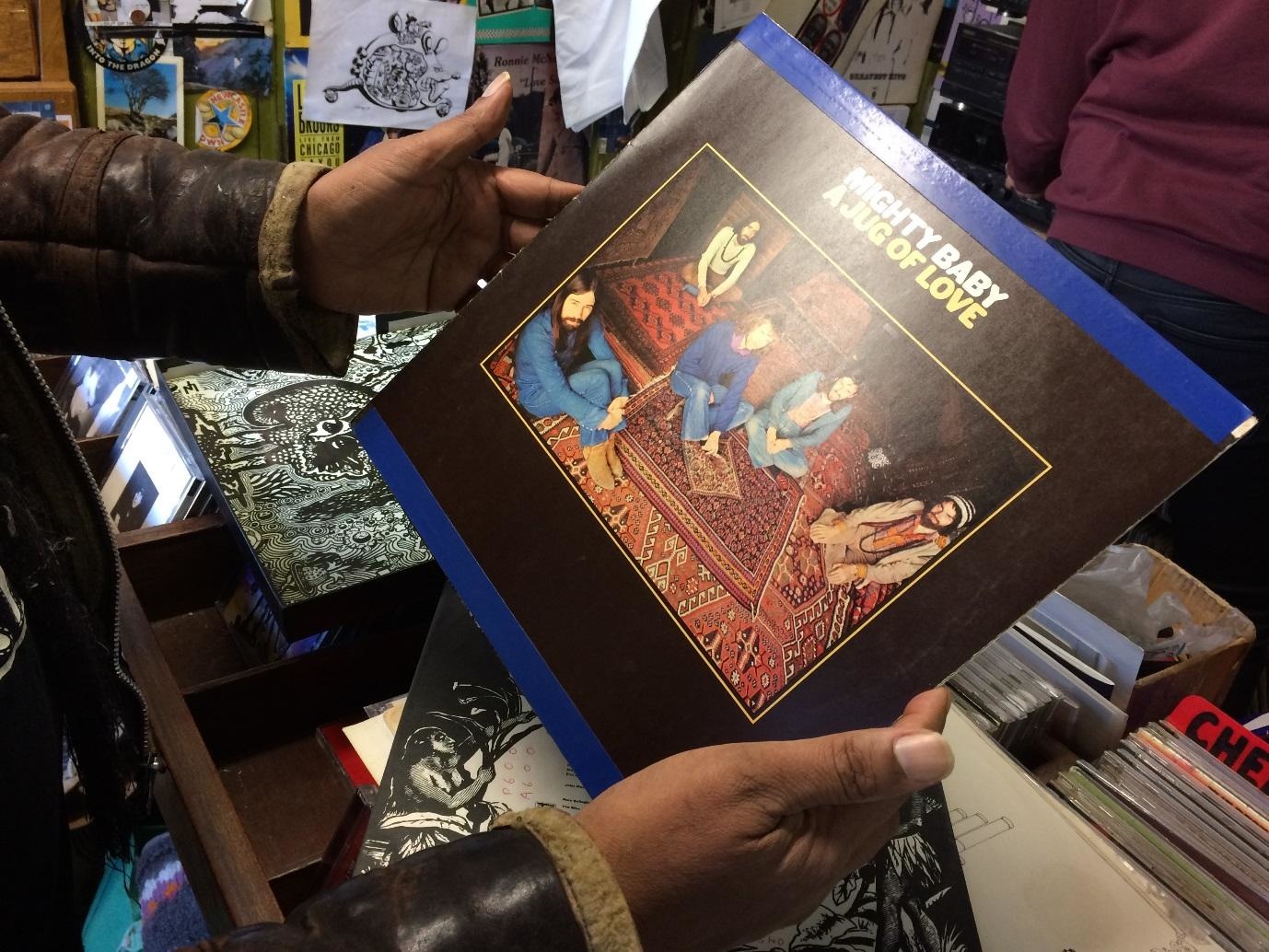

“This is my favourite band, The Mighty Baby. This is a signed copy, but look what he’s done (points to the blue masking tape)! This is a tragedy. A £600, £700 LP and look at that.”

How much would it take for you to part with your collection?

I would never do it, I’ve always been frightened of that really. I’m in my fifties’ now though and you have to start thinking about other things. I don’t want to get to the position where I die and somebody buys the whole thing as a lot. I want to make sure something happens to the collection if I don’t get rid of it before myself.

What keeps you so committed?

It helps me deal with my OCD better. I have what is called “beneficial OCD.”

PAUL

Navigating my way through a wilderness of six record-filled greenhouses and two haphazard sheds, I find Paul. A man who has collected, bought and sold vinyl for a living throughout his life. He studies sleeves, packs records and works during my visit, as a copy of Supertramp’s Crime of the Century spins on the deck in the background. He’s very direct, and doesn’t mix his words, so I use him as a sounding board for some questions about the current state of vinyl.

You must have a unique perspective on the “vinyl resurgence”—have any middle-class, mid-20s, craft beer-drinking, bearded characters strolled into your world over the past five years?

I’ve been in situations recently where I’ve seen guys like that walk into shops and they just get manipulated into buying absolute rubbish by the owners. By massaging their egos, making them feel like they’ve got knowledge, they’ve persuaded them to buy any shite for inflated prices.

Do you subscribe to the whole idea of a “resurgence?” Do you buy it?

A bit. I see a lot of shops opening up which are run by guys who are coming towards the end of their useful lives. I don’t know how long that will last—I don’t see young, fresh faces at record fairs. I just see a sea of grey. I don’t really see a resurgence in second hand vinyl in that respect. I was expecting it to be vibrant but they’re finding it so hard to find collectible vinyl in good condition that they’re having to do a lot of the reissue stuff.

What about reissues outselling new releases for the first time?

Well how do new bands get their stuff on the market? It’s far easier for a new shop to stock old James Brown albums than to risk paying money on a band who is going to be liked by one person that comes in. They’ve got to go for the occasional mum and dad coming in looking for a Hendrix LP as opposed to somebody who wants that new Shitting Toadstools LP they love.

Do you think that the vinyl resurgence will last?

I don’t think it will go any further than it has. I think it’ll stagnate for a generation because there’s not going to be a big enough variety of stuff being produced. Record labels simply don’t have the money to invest in the stuff. So no, I can’t see it continuing on the trajectory it’s supposed to be on.

How do you feel about Record Store Day?

I think it’s slightly tainted by the fact that I know small record shops don’t make money. It’s interesting and a bit of fun, but I don’t think it’s a successful business model.

And what about the news that Tesco stores are stocking vinyl?

You know what, whenever people told me, “Vinyl is making a comeback, Paul”—I just want to piss in their coffee whenever somebody says that—I say, “I’ll believe it when I see it in Tesco.” And then, low and behold, it happened—Tesco are selling Iron Maiden’s new LP. I saw how they were selling their stuff though and they were putting security tags through the sleeve! A giant hole through the sleeve? Nobody’s going to want that.

A peek in one of Paul’s many sheds.

What’s the closest to the edge that your relationship with vinyl has taken you?

Well, I’ve always been a workaholic. So when I had to make extra money, I had to go and get a job, which was absolutely vile.

What did you do?

I was an accountant at Virgin. Well, I started out as a rag-arse office clerk at a different place but I worked my way up and qualified, then became one. I was still doing the records but, at this time in particular, I needed the extra money. I was the only wage earner in a household with six children, which I just couldn’t afford. I used to leave home at 6 AM to go to London and then I’d work from 9 AM until around 6 PM. Then I’d leave and have calls [relating to vinyl purchases] booked the whole way back, so I’d be doing them around 8:30 PM until 10 PM. I’d get home, have something to eat, crash out, and then get up at 5:30 AM to go to London again and do the same thing. Then at the weekends I’d be doing record fairs on Saturday and Sunday. Once, when I was on the way back, I fell asleep on the motorway. I was woken up by the car going along the ridges that segregate the road from the hard shoulder. Just ridiculous, really. But I never saw vinyl as a burden in my life, I was just glad I was able to do it. It’s not any stealer of time, because it’s as much a part of me as my hands.

How has it impacted on your life?

It may have had an impact on the people around me. It’s selfish what I do, but I do it for selfless reasons. I’m different to the five most serious collectors I know in that they’re still single and don’t have families, where as I do.

What kind compromises have you made that those collectors’ haven’t had to?

Well, I’ve never been able to keep hold of any of my more valuable stuff for a start. I’ve had original Beatles’ demos, Sex Pistols acetates, and other things worth thousands, but as I’ve always had to concentrate on fast turnover, so they’ve had to be sold. I had six children so I haven’t had choices since about 1981, but it’s stopped me from falling into the same traps of loneliness, addiction and seeing my collection as a measure of my social standing on planet earth, which other collectors do.

You can follow Oobah on Twitter here.

More

From VICE

-

Photo: Ethan Miller/Getty Images -

Photo: Visionhaus -

Screenshot: Nintendo