Memes, as any alt-right Pepe sorcerer will tell you, are not just frivolous entertainment. They are magic, the stuff by which reality is made and manipulated. What’s perhaps surprising is that this view is not so far off from one within the US defense establishment, where a growing body of research explores how memes can be used to win wars.

This recent election proved that memes, some of which have been funded by politically motivated millionaires and foreign governments, can be potent weapons, but they pose a particular challenge to a superpower like the United States.

Videos by VICE

Memes appear to function like the IEDs of information warfare. They are natural tools of an insurgency; great for blowing things up, but likely to sabotage the desired effects when handled by the larger actor in an asymmetric conflict. Just think back to the NYPD’s hashtag boondoggle for an example of how quickly things can go wrong when big institutions try to control messaging on the internet. That doesn’t mean research should be abandoned or memes disposed of altogether, but as the NYPD case and other examples show, the establishment isn’t really built for meme warfare.

For a number of reasons, memetics are likely to become more important in the new White House.

To understand this issue, we first have to define what a meme is because that is a subject of some controversy and confusion in its own right. We tend to think of memes from their popular use on the internet as iterative single panel illustrations with catchy tag lines, Pepe and Lolcats being two well known known examples of that type. But in its scientific and military usage a meme refers to something far broader. In his 2006 essay Evolutionary Psychology, Memes and the Origin of War, the American transhumanist writer Keith Henson defined memes as “replicating information patterns: ways to do things, learned elements of culture, beliefs or ideas.”

Memetics, the study of meme theory and application, is a kind of grab bag of concepts and disciplines. It’s part biology and neuroscience, part evolutionary psychology, part old fashioned propaganda, and part marketing campaign driven by the same thinking that goes into figuring out what makes a banner ad clickable. Though memetics currently exists somewhere between science, science fiction, and social science, some enthusiasts present it as a kind of hidden code that can be used to reprogram not only individual behaviors but entire societies.

Image: @altright_es

For a number of reasons, memetics are likely to become more important in the new White House. Jeff Giesea is a former employee of tech giant and Trump donor Peter Thiel, and an influential organizer within the alt right who was prominently featured in recent profiles on the movement and its ties to the Trump administration. Giesea is also the author of an article published in an official NATO strategic journal in late 2015—just as the Trump campaign was really building steam—entitled “It’s Time to Embrace Memetic Warfare.”

“It’s time to drive towards a more expansive view of Strategic Communications on the social media battlefield,” Giesea said in his essay on the power of memes. “It’s time to adopt a more aggressive, proactive, and agile mindset and approach. It’s time to embrace memetic warfare.”

Giesea was far from the first to suggest this. Some forward thinkers within the US military were interested in how memes might be used in warfare years before the killing and digital resurrection of Harambe dominated popular culture. Public records indicate that the military’s interest in memes picked up after 2001, spurred by the wars against jihadist terrorist groups and the parallel “War of ideas” with Islamist ideology.

Despite the government research and interest inside the military for applying memes to war, it seemed to be insurgent groups that used them most effectively.

“Memetics: A Growth Industry in US Military operations” was published in 2005 by Michael B. Prosser, then a Major and now a Lieutenant Colonel in the Marine Corps. Written as an assignment for the Marine Corps’ School of Advanced Warfighting, Prosser’s paper includes a disclaimer clarifying that it represents only his own views and not those of the military or US government. In it, he lays out a vision for both weaponizing and diffusing memes, defined as “units of cultural transmission” and “bits of cultural information transmitted and replicated throughout populations and/or societies” in order to “understand and defeat an enemy ideology and win over the masses of undecided noncombatants.”

Prosser’s paper includes a detailed proposal for the development of a “Meme Warfare Center.” The center’s function is to “advise the Commander on meme generation, transmission, coupled with a detailed analysis on enemy, friendly and noncombatant populations.” Headed by a senior civilian or military leader known as a “Meme Management Officer” or “Meme and Information Integration Advisor,” Prosser writes, “the MWC is designed to advise the commander and provide the most relevant meme combat options within the ideological and nonlinear battle space.”

Subscribe to the Motherboard podcast on iTunes

A year after the Meme Warfare Center proposal was published, DARPA, the Pentagon agency that develops new military technology, commissioned a four-year study of memetics. The research was led by Dr. Robert Finkelstein, founder of the Robotic Technology Institute, and an academic with a background in physics and cybernetics.

Finkelstein’s study of “Military Memetics” centered on a basic problem in the field, determining “whether memetics can be established as a science with the ability to explain and predict phenomena.” It still had to be proved, in other words, that memes were actual components of reality and not just a nifty concept with great marketing.

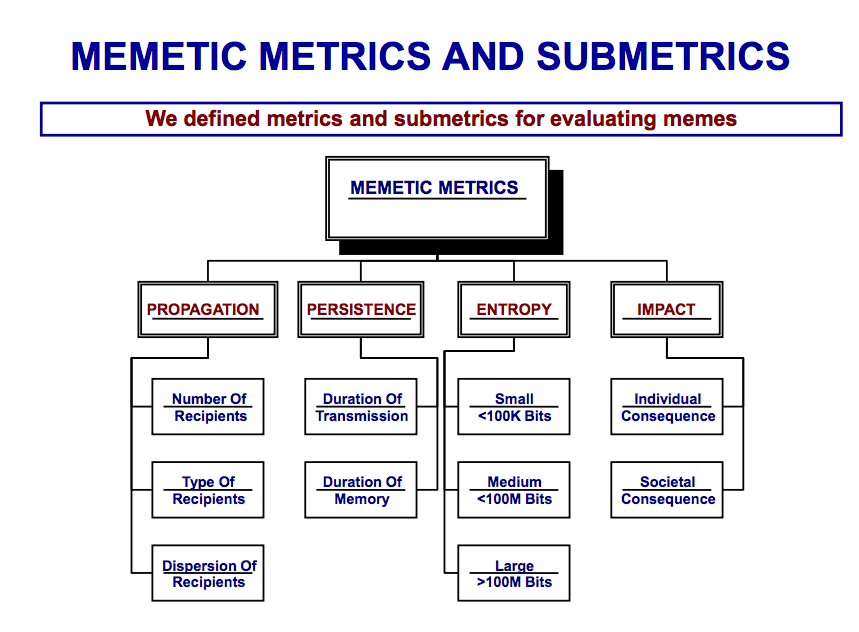

Finkelstein’s work tries to bring memetics closer to hard science by providing a “meme definition for Military Memetics,” that is “information which propagates, has impact, and persists (Info-PIP).” Classifying memes according to this definition, and separating them out from all the ideas that don’t count as memes, he offers metrics like “persistence” to measure their effectiveness.

Despite the government research and interest inside the military for applying memes to war, it seemed to be insurgent groups that used them most effectively. During the early stages of ISIS’ war in Iraq and Syria, for instance, the group used memes to captivate an international audience and broadcast its message both to enemies and potential recruits.

One of the first public applications of the research into memetics and social media propaganda was the State Department’s 2013 “Think Again Turn Away” initiative. The campaign‘s attempts to counteract ISIS social media propaganda did not turn out well. The program, according to director of the SITE Intelligence Group Rita Katz, was “not only ineffective, but also provides jihadists with a stage to voice their arguments.” Similar to how ISIS supporters hijacked the government’s platform, a year later activists used the NYPD’s own hashtag to highlight police abuse.

“Look at their fancy memes compared to what we’re not doing,” said Sen. Cory Booker to other members of the Homeland Security Committee during a 2015 hearing on “Jihad 2.0.” Booker’s assessment has become increasingly common but some critics question whether focusing on a “meme gap” is an effective way to combat groups like ISIS.

“I’ve never seen a military program in that area that was effective,” John Robb, a former Air Force pilot involved in special operations and author of Brave New War: The Next Stage of Terrorism and the End of Globalization, told Motherboard. As he sees it, the US military will always be at a structural disadvantage when it comes to applying memetics in war because, “the most effective types of manipulation all yield disruption.” According to Robb, “the broad manipulation of public sentiment is really not in [the military’s] wheelhouse,” and that is largely because, “all the power is in the hands of the people on the outside doing the disruption.”

Meme wars seem to favor insurgencies because, by their nature, they weaken monopolies on narrative and empower challenges to centralized authority. A government could use memes to increase disorder within a system, but if the goal is to increase stability, it’s the wrong tool for the job.

“Stuff like this is perennial,” Robb said about the new interest in meme warfare. “Every couple of years a new program comes out, people spend money for a couple of years then it goes away. Then people forget about that failure and they do it again.”

Image: Hillaryclinton.com

We’ve just witnessed a successful meme insurgency in America. Donald Trump’s campaign was founded as an oppositional movement—against the Republican establishment, Democrats, the media, and “political correctness.” It used memes successfully precisely because, as an opposition, it benefited by increasing disorder. Every meme about “Sick Hillary,” “cucks,” or “draining the swamp” chipped away at the wall built around institutional authority.

Trump’s win shocked the world, but if we all read alt-right power broker Jeff Giesea’s paper about memetic warfare in 2015, we might have seen it coming.

“For many of us in the social media world, it seems obvious that more aggressive communication tactics and broader warfare through trolling and memes is a necessary, inexpensive, and easy way to help destroy the appeal and morale of our common enemies,” he said.