Call of Duty fan karter0, excited that Black Ops 2 was now backwards compatible on Xbox One, booted up the game. They quickly found themselves in a compromised lobby, where a hacker had taken control and folks ran around at lightning speeds. Before karter0 left the game, worried it might flag his account for suspicious activity, he took note of the host’s gamertag. When karter0 looked them up on Twitter, they found someone charging $5 for “recoveries,” a common hacker term for a service to alter a player’s stats, in Black Ops 2.

For the purposes of this story, we’ll call this hacker Andy. He asked to remain anonymous, and as such, I’ve masked both his personal identity and the software and services he develops for Xbox 360.

Videos by VICE

Why was this a problem at all? Well, when Black Ops 2 became backwards compatible, Microsoft neglected to mention that everyone playing Black Ops 2 would be forced to do so on Xbox 360 servers. This meant joining an abandoned playground largely been taken up by hackers in the years since Xbox One launched, as Microsoft turned their security attention towards its current console.

Call of Duty images courtesy of Activision Blizzard.

“Yeah, they’ve been ignoring it since Xbox One came out pretty much,” said a hacker who goes by the name enMTW. “It’s not hard to detect these kind of services, but Microsoft doesn’t seem interested in doing anything about it. They used to ban this kind of stuff constantly. These services were incredibly expensive. Now anyone can get online and cheat like mad.”

When contacted, Microsoft urged the community to help them track hackers.

“We put gamers at the center of everything we do,” said a Microsoft spokesperson, “and we’ll continue to investigate reports from the community to help ensure that gamers on Xbox Live adhere to our Code of Conduct.”

Activision did not respond to my request for comment.

If you’ve played a Call of Duty game online before, chances are you’ve encountered a lobby like this, often indistinguishable from a normal one. Someone with a hacked console has an enormous amount of control and subversion tools. On the surface, it seemed like this Andy was luring folks into seemingly normal Black Ops 2 lobbies, screwing with their accounts, and charging $5 to fix it.

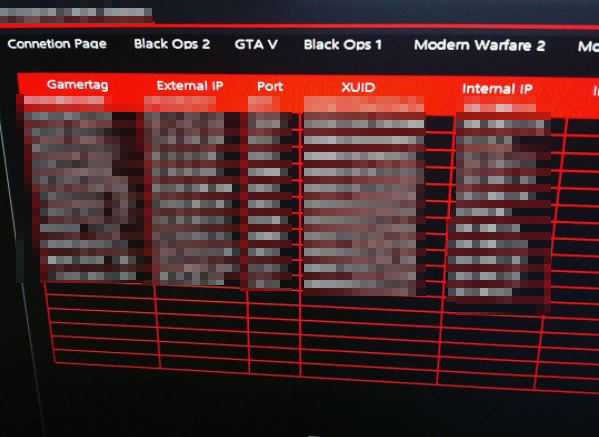

Andy, who I talked to recently over Skype, denies that Twitter account is his—”I don’t fuck with people’s accounts”—but freely admitted to operating compromised Black Ops 2 lobbies where he messes around with people. He didn’t build the tool that compromises Black Ops 2, but it certainly gives him a lot of power. He can freeze a player’s Xbox 360, kick them from the game, and even snoop around to discover their IP address, which can easily be used to learn where they live. (IPs can’t be used to pinpoint a specific location, more of a general vicinity.)

It’s not hard to look up the IPs of players who are playing game with the right tools. Image courtesy of Andy.

Typically, though, what Andy does is flip on infinite ammo and other hacks to get people’s attention, before he advertises his Instagram feed. Why Instagram? That’s where Andy’s side business lives, the place where he advertises his customized Xbox 360 software.

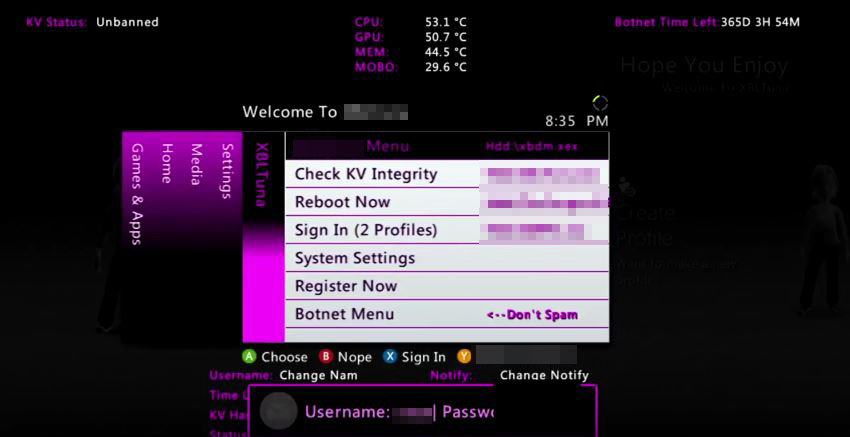

Calling it software is somewhat misleading. What Andy has built is called a stealth server, a service that allows you to slip a modded console onto Xbox Live, and when you connect, you get access to custom features specific to his software. These range from the simple—UI color customization, adding a welcome message when you login—to the ethically dubious, such as the ability to launch a DDOS attack from your Xbox 360. To someone who’s used an Xbox 360 before, it simply looks like a modified version of the interface that Microsoft had used for years, and when used in combination with other tools, like the Black Ops 2 one referenced above, it gives the user a lot of leeway to begin messing with the experiences of other people online.

Andy’s custom software looks a lot like an Xbox 360 interface.

These services often allow you to execute certain features directly from an Xbox 360, while often allowing for a direct connection to a nearby PC, which can also interact with the console.

21-year-old Andy began futzing around with consoles when he was 16.

“I’ve always been kind of techy,” he said, “so I figured, ‘Well, I’ll start modifying consoles for my friends.’”

The primary reason his friends wanted modified consoles isn’t surprising: piracy.

“I don’t condone that, of course,” he said. “I … [pause] I don’t. [pause] That’s the main reason why people want modified consoles.”

Around this time, Andy, who comes from a military family, joined the army. He put modifying on hold, partially because of the job and partially because he was tired of the clientele, which often included confused parents buying a modified console for their kids. (They usually asked a lot of questions before realizing what they were buying—and backed out.)

Money was a consideration, too. With modified consoles, it was a lump sum. People paid for the console and that was the end of the transaction. You didn’t get anything else out of them. The people running stealth servers were charging monthly or weekly subscriptions for access.

He took a look at stealth servers and the software people were downloading to their modified consoles. They were built on the same coding languages he’d been learning in his spare time.

“I took a look at the source code,” he said, “and realized ‘Holy crap, this is a language I already know. I can do this. Why am I paying for something I can do?’”

“I’ve read very carefully the laws that surround this [laughs]. I’m just the middleman. I’ve definitely covered my ass on that.”

Andy launched his own service a few years back, but nobody paid attention. After partnering with some others in the scene on a server, he decided to refocus his efforts by building features you couldn’t find elsewhere. This is how he landed on being able to launch a DDOS attack from an Xbox 360, which a friend suggested and he took on as a challenge.

It takes roughly a week and a half for Microsoft to discover a stealth server that Andy has spun up. After it’s blocked, it’s little effort for Andy to spin up another one. Rinse, repeat.

When I asked Andy about how modified consoles are often used for piracy, he hedged and said that’s not what he built them for—it’s just what people could use them for. He took the same approach when I pressed him on what good it does to allow people the ability to easily launch a DDOS attack through a console. Andy didn’t deny DDOS attacks are inherently malicious, saying he builds them into his service because it’s something no one else provides.

“I’ve read very carefully the laws that surround this [laughs],” he said. “I’m just the middleman. I’m not providing a botnet. I’m not providing any of the servers that do this. I’m just providing an input. I’ve definitely covered my ass on that.”

(A botnet is a network of compromised Internet-connected devices, which can include anything from computers to thermostats, being asked to perform tasks, such as a DDOS attack.)

For the record, every legal expert I ran Andy’s theory by told me it was bullshit.

“I would take anyone’s claims of avoiding liability on a technicality with a heavy grain of salt,” said attorney Ryan Morrison of Morrison/Lee, a gaming-focused firm. “It’s almost impossible to guarantee that with certainty, and it always comes down to the facts of each individual case.”

An advertisement for Andy’s services, which he sells via Skype.

In any case, Andy sells access to his software at $40-per-month or a flat rate of $100. The influx of new people playing Black Ops 2—at times, upwards of 70,000 have been online, tens of thousands more than what the game has seen in years—has proven profitable for him.

Andy isn’t getting rich off his software, but according to him, it’s enough to pay for some beers. When we spoke, he’d only made $40 on that particular day, but a more recently fruitful day had resulted in as much as $230. In addition to the money that comes from people who stumble upon his service, he relies on other people to sell it for him. He takes 70% of the sale.

Andy is small fry in the world of modifications and hacks. It’s part of the reason he was even willing to talk with me. But he represents a regular cycle in the video game world, where old hardware is phased out and tinkerers begin to pick it apart. Some of it is benevolent—it’s what leads to emulation, a form of archiving video game history—and some of it’s undeniably questionable, like the ability to launch a DDOS attack. It’s basically a digital wild west.

It’s unclear how being able to launch a DDOS attack helps anyone, but it’s also on Microsoft for reviving Black Ops 2, knowing full well what’s happened to security on that platform. Black Ops 2 is back, but it’s also full of people who want to fuck with you.

There doesn’t appear to be an endgame for Andy, nor does he strike me as someone who’s purposely malicious—just indifferent. To an outsider—or someone who runs across one of his lobbies—there might not be a difference.

“I’m mainly just doing this as a project so I can gain a better understanding of what’s going on and really perfect my coding abilities,” he said.

Follow Patrick on Twitter. If you have a tip or a story idea, drop him an email here.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: YouTube/FunkopotamusWes -

Screenshot: Xbox -

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

Screenshots: YouTube/Xbox, YouTube/PlayStation