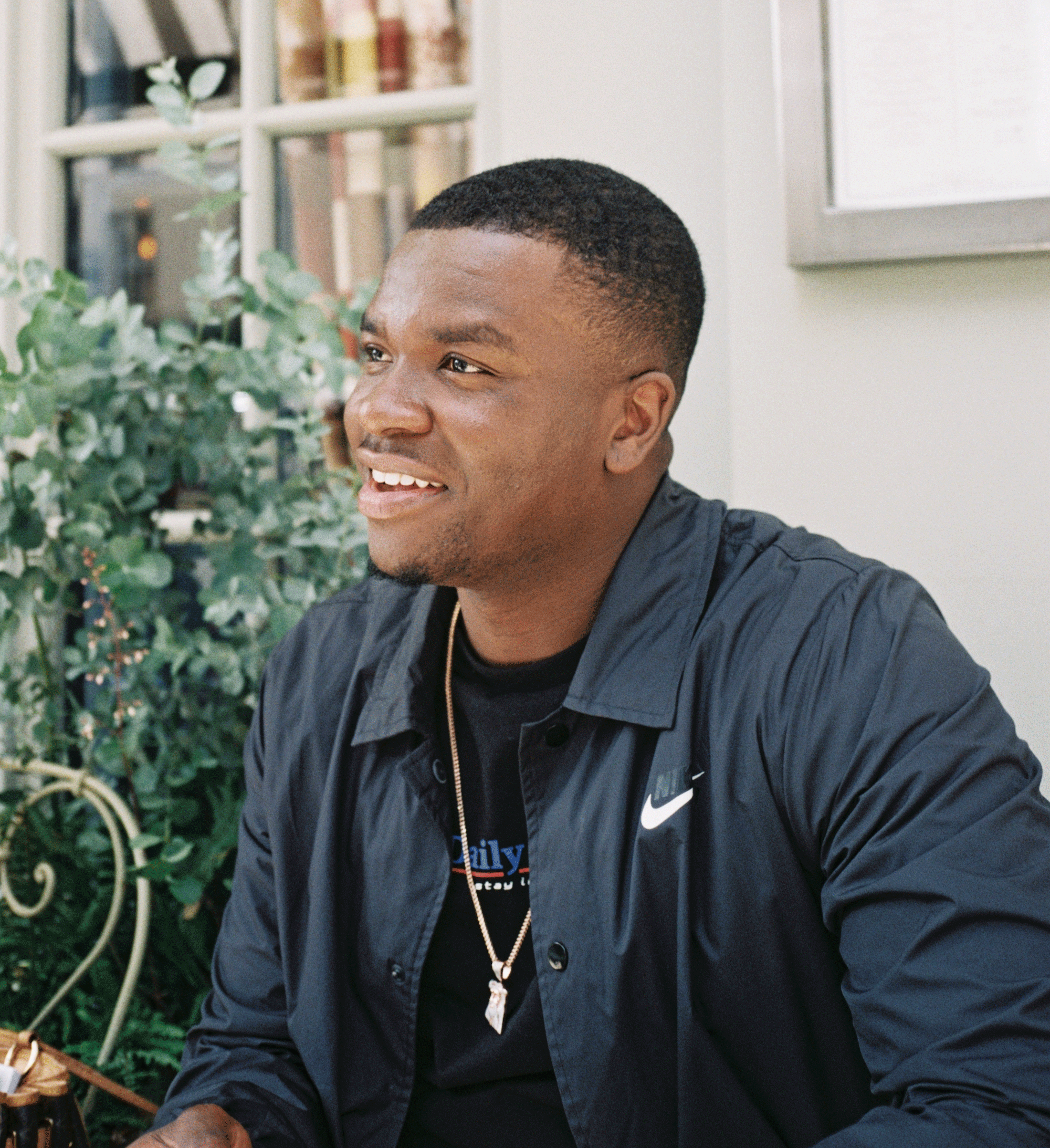

Michael Dapaah has a vision board and he won’t tell me what’s on it.

So far, I’ve managed to establish what it looks like: a cork board covered in pictures that represent his goals, from the personal to the professional. “I don’t really share that,” he grins, when I ask what 2019 looks like. But after some light pleading from my side of the narrow cast iron table we’re sitting at, on the terrace of an artsy Soho hotel, he relents.

Videos by VICE

“There was jet-skiing,” he admits. “I did that in January after wanting to go for about three years. If there’s certain things I don’t do the previous year, I just carry them over.”

What else?

“Producing the second season of #SWIL [Somewhere in London, Dapaah’s acclaimed YouTube series], of course,” he continues. “Reading 12 books a year. I’m on my fifth, but it’s tricky when you’re so busy. I probably got through six pages in the last three weeks of the book I’m currently reading.”

That book, ironically, is all about vision. “It’s called The Power of Vision, by Dr Myles Munroe,” says Dapaah. “Everything starts from a vision. You envisaged yourself doing this, or something like this, right?” he says, gesturing enthusiastically towards my dictaphone. “VICE, whatever, it all starts from someone who saw an opening and said, ‘Cool, we can create something.’ Vision is so important.”

Michael Dapaah is a big believer in vision – and in his case it seems there’s something to be said for it. Even those not acquainted with the 28-year-old comedian by his real name will recognise his face – or his ad libs. In 2017, Dapaah hit the aspiring content creator jackpot; he went viral, in the guise of Big Shaq, a roadman rapper attempting to make it big.

Shaq was one of four characters featured in the first series of Dapaah’s mockumentary #SWIL, which was already creating healthy buzz on its own; the episodes had racked up around one million views well before Shaq’s appearance on Charlie Sloth’s BBC 1Xtra slot “Fire in the Booth”. But once the clip of Shaq rapping “Man’s Not Hot” – an ode to the insistence of London’s roadmen of sporting their uniform of puffa jackets, whatever the temperature – dropped online, the game was on. “The ting goes… SKRRRRA PAP PAP” spat Dapaah, and a million memes were born.

What followed was an intense period of mega global fame: brands came banging down the door; the likes of DJ Khaled appeared in a slickly produced music video for the track; and Dapaah cracked the million subscriber mark on both YouTube and Instagram. Big Shaq turned up at the BET awards, while Dapaah – as himself – was booked on Nike campaigns and signed a deal with Island Records.

This narrative might seem familiar. Individual goes viral. Then, Dorothy-like, they’re swept up in a tornado of money and attention, before being supplanted by the next internet celebrity and deposited indecorously back onto solid ground, usually struggling to build a career from the shreds of whatever one-time joke they owed their initial fame to.

From the outside – and to those who weren’t familiar with Shaq’s origins as one character in a bigger ensemble cast project – it could seem as though Dapaah was taking this well-trodden path. After all, it’s taken two years for the new season of #SWIL to drop (it’s streaming now, have a watch). But, Dapaah tells me, the delay was a carefully plotted one; he wanted the mayfly cycle to end before any new moves were made. It is, as he says, all about staying true to your vision – and Michael Dapaah’s vision does not include burning out.

“If I’d made season two of #SWIL when Big Shaq went viral, it might have got the views, but it wouldn’t have been produced or written to this standard,” says Dapaah. “I don’t ever want to shortchange myself when I’m creating. I wanted to make sure I properly took the time; went back to my quiet place.”

It took about a year-and-a-half for Dapaah to be able to get back to his “quiet” place. Demands on his time – mostly musical – were endless.

The viral fame, he says, wasn’t the difficult bit – he was prepared for that: “Not even in a cocky way,” he says, “I saw what else was going big; I knew the work we were putting out was good stuff. So eventually someone was going to catch onto it.” What did come as a surprise was that it was Shaq who exploded. Dapaah had intended for another character, MC Quakez, to be the breakout star, but mainstream appetites had other ideas.

“Quakez spits on grime, 140 bpm,” explains Dapaah. “That’s not digestible for everybody. Shaq is more of a versatile artist; he can rap over different beats. And I think the narrative for him is stronger – people just naturally gravitated to him.”

Getting back to creating, one struggle was returning to the slower pace of making a mockumentary after being immersed in the industry whirlwind that is marketing a novelty track.

“That was the most difficult thing,” he laughs. “Music is such a fast-paced industry. It’s straightforward in terms of: you produce a track, release it. With acting and comedy it takes time to write, direct and produce. There was that challenge of being able to sit down to write and not thinking I needed to get up and do something else because I was so used to being on the go. It wasn’t even about getting back to pre-2017, pre-fame Michael state-of-mind; I needed to tap into different things. I wasn’t trying to produce what I’d done before – I was trying to produce something better.”

This has manifested in #SWIL season two, which sees an expanded character list, alongside the original four who appeared in the first series. This includes Damien, a faded American rapper trying to revive his career via acting; one of his recent television credits is Love & Hip Hop: Nebraska.

Damien’s inclusion is testament to Dapaah’s focus on the macro, which unveils itself during the course of our chat. Talking to him, you wouldn’t guess he’s primarily a comedian – he doesn’t crack jokes or make self-deprecating gags about his ambitions. Instead, he’s thoughtful. Analytical. Featuring an American character like Damien was a move born of what could be termed “creative savviness”. Dapaah has an American audience to build on and is conscious of it, so he created someone who’d speak to them. For this realisation, Dapaah cites an unusual inspiration: Mr Bean.

“Being blessed to travel to so many places, you get to understand different cultures and what connects,” he says. I catch a flash of a glittering watch as he adjusts his sleeve. “Take someone like Rowan Atkinson. His portrayal of Mr Bean ended up being so successful because it was physical comedy with minimal English, which allowed it to penetrate into territories like Japan. For me, it’s about the work being able to cross over. For example, some people who have an African background will understand Dr Ofori [Dapaah’s Ghanaian Uber driver-cum-life-counsellor character, a particular favourite of #SWIL fans]. But people not from that background will also take to him because it’s like, ‘Oh, I’ve had an Uber driver like that.’”

I’m surprised by the Rowan Atkinson nod, and say so. Dapaah becomes pleasingly animated, shifting in his chair. He admires Atkinson’s work a lot, he tells me, along with that of Matt Lucas and David Walliams. “I just think they’re geniuses, the way they portray people,” he says. Surprisingly, it’s not Little Britain that does it for him, but Lucas and Walliams’ widely-panned mockumentary follow-up, Come Fly with Me.

Mockumentaries are Dapaah’s preferred format: staying with characters across an entire season allows him to build narrative arcs for them, give them a journey. Despite its seemingly light content, Dapaah has baked strong social messages into the foundations of #SWIL. They might go over the heads of the likes of me – middle-class journalists from the countryside – but Dapaah’s intended audience are going to hear them, loud and clear.

“Take episode one,” he explains. “The dudes with the ballies [balaclavas] on, who get in the back of the car and are planning to do a robbery. Dr Ofori says, ‘If it’s finances you’re after, work hard.’ A robbery is 25 years for 25 bags. And obviously balaclavas are such a thing now, youts and that trying to cover their faces in the ends…”

“They are?” I interject. “I live in Dalston…” At this, Dapaah cracks up, calling over one of his entourage. “Yooo, listen to this,” he crows good-humouredly. “She lives in Dalston and doesn’t know about youts covering their faces with the ballies!” There’’s some giggling before he sobers up again, shaking his head. “That’s everywhere. These youts… it’s like they don’t even understand what they’re doing.”

This is something Dapaah is all too familiar with. He was raised in Croydon, and while he performed well at school he was also drawn into the underbelly that often arises in areas where young people have little to do and a lot of time to it, and systematic deprivation offers few opportunities as adults. There was time spent in prison, but I don’t ask about that and he doesn’t mention it. Instead, he speaks of the responsibility he feels to the community he grew up in, and all the ones like it where young would-be Michael Dapaahs sit on their phones watching videos of a man who was once indistinguishable from them.

“I’m a council estate boy,” he says. “I didn’t grow up with my parents owning their house or being able to live where I’m blessed to live now. Whether you like it or not, when you’re in the public eye, you have responsibility – people look up to you, sometimes as their form of escape. People look to you for inspiration. It’s up to you whether you’re going to feed them the right or wrong things. It’s so important to me to go back. I shot a lot of series two of #SWIL at Pollard’s Hill, where I grew up. I rep that. My friends from that era tell how much it means to them.”

Dapaah’s upbringing may have had downsides, but it’s also what he credits for instilling in him the drive that’s pushed him this far without having to try to break into comedy the more traditional way, via stand-up, Edinburgh Fringe, Live at the Apollo. These avenues didn’t offer Dapaah the creative control he craved, so he turned to social media instead. Plus, all of those routes are overwhelmingly white.

Dapaah has always been the class clown, a title he claims proudly (“We used to do dumb stuff, man”), but it was while studying for a BA in Film, Acting and Theatre at Brunel that he started making comedy shorts. His parents wanted him to study medicine, like his father, but Dapaah didn’t like blood. Instead, he poured the discipline and grind his father had ingrained in him into his creative passion.

“They come from an environment where they’ve had to build everything from scratch,” he says of his father, a first-generation immigrant. “That’s what’s been instilled in us. For me, getting in the game pushes you more as well, because you see the lack of people like yourself in the industry.”

Dapaah is one of a wave of young black comedians, like Tom Moutchi and Mo Gilligan, who’ve circumvented the traditional gatekeepers of comedy and used social media to build powerful fanbases. He doesn’t need the established institutions of mainstream comedy, such as Mock the Week, to reach his audience. But does he care, I wonder?

“I think it’s important for them to recognise,” he says, thoughtfully. “But it’s not imperative. We can still flow and make things happen. To make real shifts and crossover, you do need to have TV and film.”

He’s had offers to make the leap, of course. But the BBC were proposing putting #SWIL on online-only channel BBC Three – a space Dapaah already dominates. “I’ve got more subscribers than them, it doesn’t make any sense,” he observes (BBC Three has 1.7 million subscribers, Dapaah has 1.5 million – but in fairness, all 1.5 million are there exclusively for Dapaah, rather than the broad range of videos posted by BBC Three).

There have been good conversations with Channel 4, he confides, but he turned down offers of a talk show because both Big Narstie and Mo Gilligan have recently launched theirs. Dapaah’s not about to let himself and his fellow black creatives be boxed off into one niche now they’re finally forcing the mainstream to take note.

“This thing is bigger than me now,” he says, inadvertently quoting Beyonce. “It’s about us. It’s about making people respect us and know that, cool, we have talent. Mo and I do completely different things. Don’t just group us together.”

What’s next, then? What does Michael Dapaah want to carry over on the vision board for 2019?

“I want people to say… ‘Wow,’” he says slowly. “I want them to see the different sides of me; to see that great work.” At that moment, a man approaches. “Big Shaq!” he exclaims. Dapaah grins and gives him a handshake. The legacy, it seems, is secure.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Bandai Namco Entertainment -

-

-

Photo by Neil Lupin/Redferns