This is the fifth in a series of articles featuring immigrant-owned restaurants—in this case, a restaurant owned by the child of immigrants—in enclaves located outside of major US cities.

Sue Nguyen-Torjusen and her husband were some of the first civilians to return to Biloxi, Mississippi after Hurricane Katrina. The cameras were pointed at New Orleans but 100 miles east along the Gulf Coast in the little casino town, Nguyen-Torjusen’s house was down to the studs. Her personal belongings were on other people’s rooflines. Water from the storm surge had filled her neighborhood and returned to the bay with many of her memories. The force of the wind had driven a Sharpie pen into the wall, sticking out like a dart. Shoes from her closet were hanging from a ceiling fan.

Videos by VICE

They made their way to Le Bakery, the restaurant they owned. A house was sitting on the railroad tracks that run directly in front of it. The windows were blown out and the inside looked like a muddy milkshake but the structure was built as a seafood market after Hurricane Camille, so it was elevated to meet code and constructed simply, with rebar and vents underneath the tiles to accommodate the drainage of shrimp and fish water. The neighborhood was at a higher elevation so the water damage was minimized.

“We have a bakery,” Nguyen-Torjusen recalled saying. “We have a shell. We have a building.”

She grabbed a can of black spray paint and walked out front to the plywood covering the door. In other parts of the county, FEMA workers would spray X-marked codes onto this kind of plywood, denoting, sometimes, the number of fatalities in the building. Nguyen-Torjusen sprayed a message: “Bread will rise again. It kneeds time.”

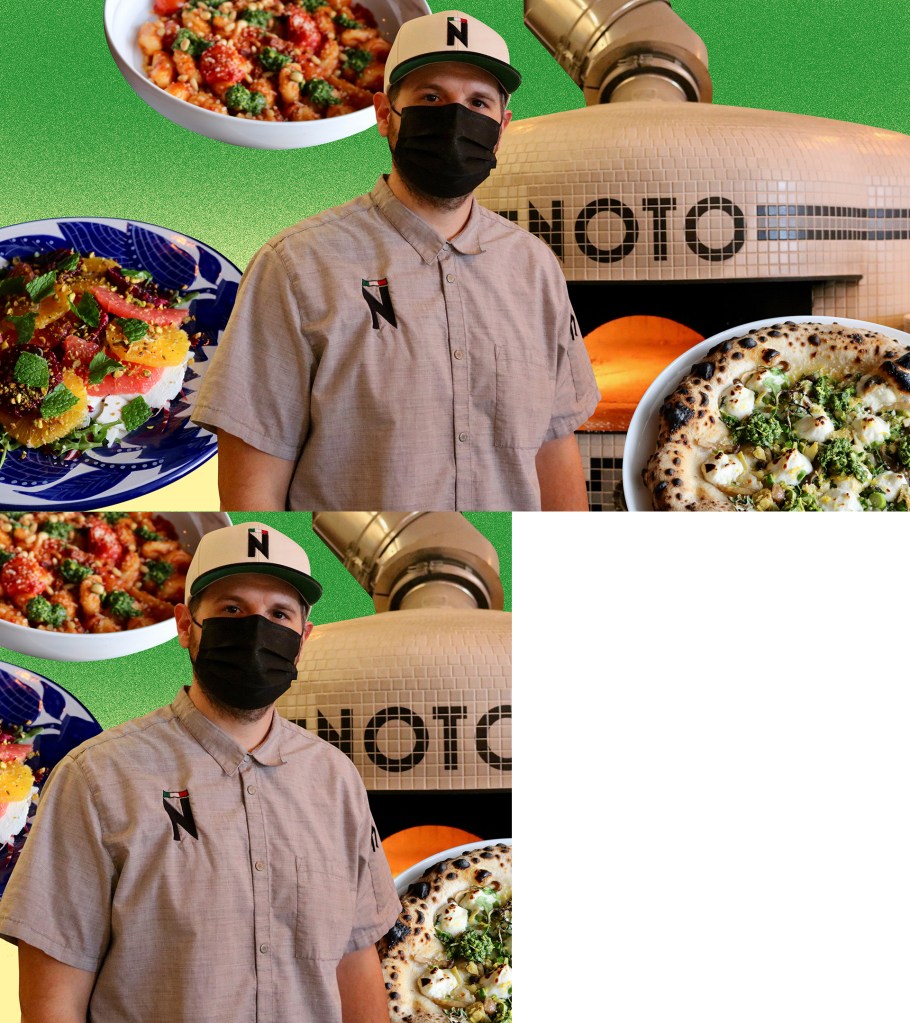

Inside Le Bakery. Photos by Nick Gomer.

For Nguyen-Torjusen, a proud southerner who was raised in Biloxi—the home of Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederacy—it was a play on the post-Civil War rallying cry: The South Will Rise Again.

Nguyen-Torjusen was conceived in South Vietnam just before the fall of Saigon, and born in San Diego, where her parents fled. When Nguyen-Torjusen was in second grade, the family drove east along the Gulf Coast and stopped for good in Biloxi, where her father wanted to work as a fisherman, like many of the other Vietnamese immigrants in the area. On his first day out on the boat, however, he got seasick. Instead, the family opened a market: Huong Que, “The Old Country.”

The Biloxi area is home to some of the densest populations of Vietnamese immigrants in the United States and, even in second grade, Nguyen-Torjusen served as a hinge between the Southern and Vietnamese cultures, translating at the market and in school.

“It’s almost parallel in the sense that Vietnam was colonized by the French,” she said. “Same as Louisiana and everything else. When I joke around with the Boudreauxs and the Thibodeauxs down here I say I’m just as much Cajun as you are in that sense. I think a lot of it shows in the cuisine too: the love of food, spices, flavors.”

Baguettes for sale at Le Bakery.

Nguyen-Torjusen’s father was a chef. Her mother has always been adventurous in the kitchen; Nguyen-Torjusen remembers her rigging up a bar so that she could teach herself how to pull taffy. Her home was thick with an appreciation for both Vietnamese and Southern cuisine. But most of Nguyen-Torjusen’s recipes are a result of her own experimentation. She went to a local college as a business major but spent her nights learning how to bake.

“My roommates would tell you we were total fatties in that sense,” she said. “We came up with some of the best recipes in that late night whatever.”

She started selling bread and pastries out of the family market. Her father died in 1999 and she opened Le Bakery—a play on the French influence and an homage to her mother, Le—in 2002.

I first visited the bakery in 2008, when the city was still in shambles after Katrina. I remember being struck by its specificity, particularly in a town that was so deeply wounded and, being a casino hub, seemed generic and corporate on its surface. The shop smelled like sweet bread. Some of the bubble teas had the consistency of a smoothie or a slushie. Cops, Vietnamese immigrants, and Americorps volunteers lined up for the cream cheese turnovers coated in chocolate or stuffed with lemon filling. I spent two months living in a trailer in a field in the middle of town, working demolition jobs. Walking in the shadows of the Hard Rock Casino, tearing apart homes in abandoned backwoods neighborhoods, finding left-behind family polaroids, or porn, or calendars with never-completed plans, Biloxi’s detachment and loneliness turned my stomach. Le Bakery was the only place that felt like a true community gathering space. In truth, it was too much for me at the time; it was easier to ignore the fact that real people still lived there.

Most popular and most exemplary of Nguyen-Torjusen’s mix of Southern pride, Vietnamese pride, and grace, are her “French Vietnamese Style Po’boys.”

“In the bigger cities, they would know what banh mis are,” she said. “You know, translated, banh mi can either be ‘sandwich’ or ‘bread,’ but they give you that crossover of French influence. Like the po’boys, being on French bread, obviously, that’s the way they do it in Vietnam.”

The words “banh mi” do not appear on the menu but Nguyen-Torjusen does not shy from their origins, naming each individual sandwich in Vietnamese: Thit Nuong Nem Nuong, filled with lemongrass-garlic grilled pork and Vietnamese sausage; or the Xa Xiu, with Chinese char siu roast pork and a honey hoisin glaze.

“We tell everyone to get everything on it because you can always take it off. Get the full-on because Vietnamese food is all about the builds of flavors, the hints of garlic, the lime, this, that, and the other,” she said.

Nguyen-Torjusen’s French breads were an immediate, community-wide hit. Today, she supplies the bread for many of the city’s most popular restaurants like the Ruth’s Chris Steakhouse in the in Hard Rock Casino and Mary Mahoney’s, a Biloxi classic that’s been serving steak and seafood since 1962 in a Vieux Carré-style house that was built in 1737.

When I returned in February of this year, Fox News was playing in the corner seating area but Nguyen-Torjusen said they rotate the news channels to keep everyone happy.

Vietnamese snacks are sold alongside king cakes and baklava.

“It’s a community meeting place but we say we’re not going to talk about calories and we’re not going to talk about politics or religion in here,” Nguyen-Torjusen said. “Leave that outside the door.”

The man working the counter knew everyone’s name except mine. Nguyen-Torjusen’s mom, Le, was still working in the kitchen. She saw a regular and, anticipating his order, returned with a strawberry milkshake. Mardi Gras was approaching and Nguyen-Torjusen was focused on her King Cake, which uses a bit less sugar in the dough than the traditional cakes.

“We don’t do any advertising,” she said. “Everything’s been word of mouth, kind of like that whole homegrown feel. I like for people to come into our bakery and not feel like it’s a cookie cutter bakery. It almost gives you a little something more in terms of lagniappe. The whole thing is I like the fact that we have different echelons of people that come in from social to economic side of things. One day you could see the mayor here. You could see the guy down the street. You could see the construction workers. The attorneys.”

Sometimes, one of the freight conductors stops the train on the tracks and runs in to buy bread.

“This never happened,” he tells Nguyen-Torjusen.

Sue Nguyen-Torjusen’s mother, Le, still works in the kitchen.

A framed photo of the plywood sign, taken by a loyal customer, now hangs prominently in the restaurant. After the flood, supply chains were down from Texas to Florida. Everyone needed the same things: Power, water, construction materials. The warehouses and utility companies had been decimated too and the routes were flooded or blocked. Nguyen-Torjusen temporarily gave up on her home and focused on the restaurant, which, fortunately, was right around the corner from the electric company and got power back relatively quickly.

“We basically were living in FEMA trailers that we pulled to the back over here because at least this way we had utilities,” she said. “My neighborhood: gone. I didn’t even start rebuilding my house until more than a year later.”

Six months after Katrina made landfall, they were one of the first establishments to reopen.

“We had a line of people out the door. It was a amazing,” Nguyen-Torjusen said. “Even then we were barely getting mail service. It was crazy. Word of mouth. Every day, people coming by to check us out, to make sure we were OK.”

Nguyen-Torjusen’s most vivid memory from that time was the return of an elderly customer who lives more than an hour inland.

“She wrote us a letter: ‘Sorry all this stuff happened down on the coast,’” Nguyen said. “‘I hope you guys are OK. I hope your whole family didn’t stay. Is the bakery going to be reopened and when can we start getting bread again?’”

When she came in, she gave Nguyen-Torjusen a hug.

“This lady, she drives from up there down to the coast for maybe literally $4 of bread, every trip she makes, and she just drives back up there herself,” Nguyen-Torjusen said. “To this day she still comes in and she calls us up and she’s like, ‘I can’t give you a credit card over the phone but I’ll come in and pick it up.’ We’re like, ‘We got you. Don’t worry about prepaying us. We got you.’”