Members of Goats & Glory—the U.S. Navy’s esports team—will not admit that they’re recruiters. The Navy esports teams have been streaming almost every night for the past week and inevitably someone asks them if they’re on Twitch to recruit and if the streamers themselves are recruiters. “I don’t recruit people,” MM1 Andrew Crosswhite said on stream in Early August. “People that’s already been recruited…I help them get their job.”

Crosswhite is technically correct, but only technically. When the Navy says “recruiter” it does not mean the same thing the public thinks of as a “recruiter.” For the Navy, a “recruiter” is a specific assignment with specific rules and designations. Technically, a Sailor would be assigned as part of “Navy Recruiting PERS—4010C1” to be considered a recruiter. Crosswhite and the other members of the Goats & Glory stream have a different assignment. They’re Twitch streamers.

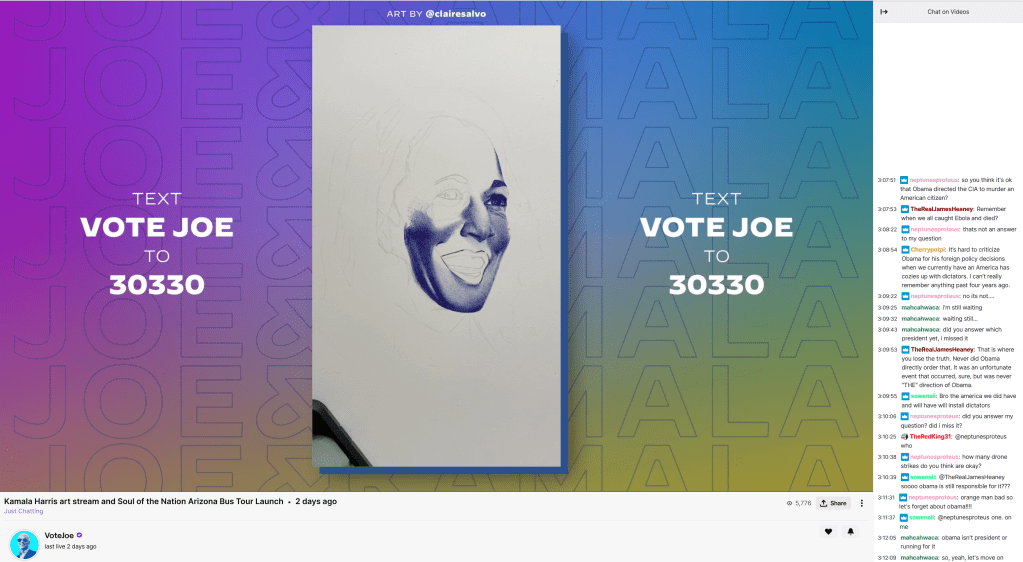

Videos by VICE

Over the past two months, Navy Twitch streamers have responded to constant prodding from viewers who are stating the obvious: The Navy is on Twitch because it needs to reach out to young people for recruiting purposes, and that’s where young people are.

The Navy’s esports team repeatedly pushes back when viewers ask them if they’re on Twitch to recruit. But, often moments after they’ve denied that they’re recruiters, the Sailors will tell viewers that they can help put them in touch with a recruit if they’re interested. “We’re not here to recruit anybody…but we do realize…that naturally, viewers might be interested in joining the Navy and we’re happy to point them in the right direction,” one member of Goats & Glory said on a recent stream.

Twitch has caused the Navy a lot of problems. Goats & Glory has been assailed by trolls asking about war crimes, is possibly facing a first amendment lawsuit for banning people from its Twitch channel, and was almost defunded by Congress. Many of these problems are of its own making. The Navy’s team members say, over and over again, that they’re streaming on Twitch as part of an outreach and awareness program. While technically true, it feels like a lie. People know that the end goal of an outreach and awareness program is recruitment. When the Navy equivocates and falls back on technicalities, it looks like a liar.

According to an unclassified memo about the creation of the Navy esports team, “The qualifications to become a team member are identical to the qualifications needed for recruiting duty…potential team member selectees will be screened for team fit and recruiting duty.”

The streaming assignment is a three year duty based in Navy Recruiting Command in Millington, TN. Some of the Goats & Glory team received recruiting training at the Navy Recruiter Orientation Unit (NORU) in Pensacola, FL. “The intent of NORU training will be to further develop communication skills and to ensure team members understand the types of information sought by those inquiring about service in the Navy.”

That’s recruitment. Everyone knows that’s recruitment. When the Navy esports teams says that it’s not, it’s failing at the very outreach and awareness it claims to prize. It’s also reinforcing stereotypes about military recruitment: that it’s predatory and that recruiters lie.

Military recruiters are such famous liars that military internet culture is full of jokes, videos, and articles about it. There are numerous military recruitment scandals. In 2014, a Marine Corps recruiter was convicted of sexual misconduct for—among other things—sending unsolicited nudes to an 18 year old woman he was trying to recruit. In 2015, Army National Guard recruiters were caught receiving bounty payments on fake recruits. The fraud was so widespread that investigators estimated it cost taxpayers $100 million. Those are just two of the more recent scandals. The list goes on.

The Military needs young and tech savvy recruits. The Pentagon’s budget has grown as the size of its all-volunteer force has shrunk. The money is going to weapons systems like the F-35, which require not just a pilot but a vast array of technical support staff. But young people, or at least the young people the military wants, don’t want to join.

After two decades of a war in Afghanistan and the disastrous invasion of Iraq, the Military’s brand is bad. The Twitch streams and esports teams are supposed to help rehabilitate that image. It’s all about “outreach and awareness.” The Navy wants its streamers to develop a parasocial relationship with the audience that gets young people excited about the Navy.

It can’t do that as long as it’s lying about why it’s online playing video games. In the past, a Navy recruiter could get away with shading the truth to a new recruit who wanted to escape their small town and see the world. That’s much harder to do when the audience is behind a computer screen with the world at their fingertips. Lying about your intentions—saying that you’re not on Twitch to recruit when you’ve received recruiter training—will only hurt the Navy’s cause.