In May of this year, Twitter found its 15th century #FreeTheNipple poster girl. In a tweet with over 61,000 RTs, King Charles VII’s royal mistress Agnès Sorel went viral with the tagline: “‘Women in the past were modest and had more respect for themselves.’ Here’s Agnès Sorel, who had her gowns tailored to expose her favorite boob in the 1440s.” So who was this courtly bad girl? It turns out that the woman also known as the Dame de Beauté (Lady of Beauty) had the King of France by the crown jewels—and changed the course of history in the process.

Born in 1422 of a family of the lesser nobility at Fromenteau in Touraine, Sorel’s “superhuman” beauty preceded her. As historian Joseph Delort wrote in 1824, “The reputation of her striking beauty soon crossed the limits of Touraine, and drew near it an infinity of magnificent lords.” But, like a bejeweled crown of exquisite luxury, her otherworldly looks were fit only for a king.

Videos by VICE

It didn’t take long for the young woman to catch Charles VII’s eye. Among many other vices, he had a weakness for women and a sensitivity to beauty. As politician and essayist François-Frédéric Steenackers wrote in 1868, “Charles VII had a crowd of anonymous mistresses, or rather a sort of harem, a traveling deer park, who followed him everywhere.” But Sorel was different; she was not only stunning, but incredibly intelligent and kind. “She had all at once, by a rare privilege, a superior beauty of the body and the soul, with this physical and moral vitality that satisfied all the demands of love.” The king was hooked.

Sorel’s infectious spirit and unmatched influence over the king inevitably spilled over to the public eye. She rarely left the king’s side, and Charles VII even attended numerous official festivals with her. No gift was too extravagant for la Belle Agnez. Among the wealth of jewelry, clothing, and properties he lavished on her, Sorel received what is believed to be the first cut diamond, as well as the fairy-tale Château de Beauté, from which she derived her famous title. Charles even gave his love the next best thing to a wedding ring: official recognition as his mistress.

Watch: The History of Black Lipstick

This unprecedented move was jaw-dropping stuff. And as Steenackers put it, “A mistress raised to the official rank of a favorite was not only a novelty, it was a revolution, which, like all revolutions, could not take place without leaving behind indignation and hatred.”

Sorel was scandalized as a devilish schemer and a slut. Many writers of the time—rivals to the crown—indulged in gossip of illicit affairs and infidelity. Georges Chastellain, ally to Sorel’s biggest adversary, Louis, the Dauphin of France and the king’s son and heir, wrote: “All the women of France and Burgundy lost much in modesty in wanting to follow the example of this woman.” He failed to mention, of course, that the “good duke” of Burgundy he also served had no less than 27 mistresses of his own.

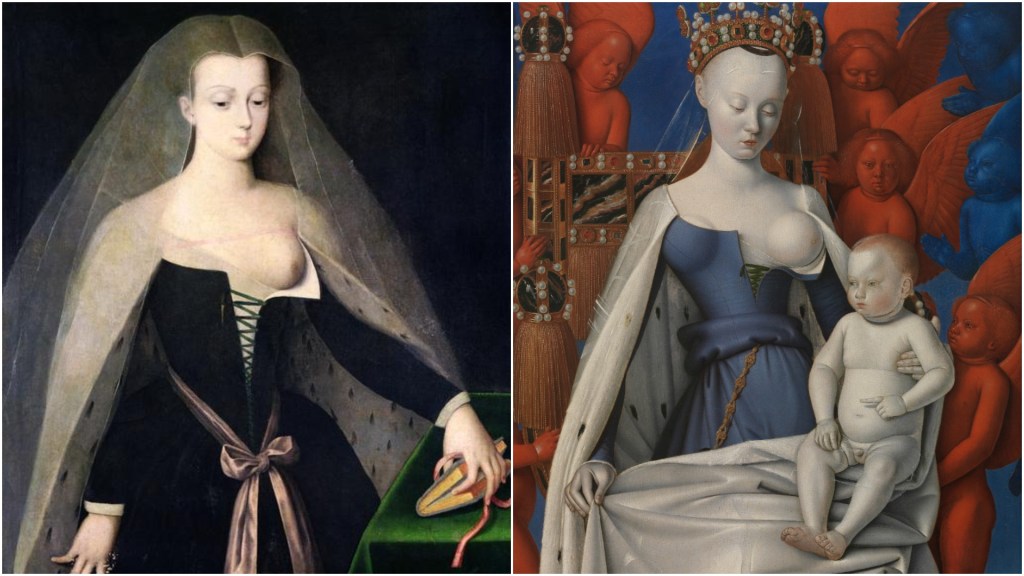

Painter Jean Fouquet crystallized the image we most associate with Sorel today; the single breast-baring Virgin in his Virgin and Child with Angels is widely believed to be modeled on Sorel. According to Rainer and Rose-Marie Hagen, authors of What Great Paintings Say, Sorel was the obvious choice for the Virgin, since she was considered by many at the time to be “the most beautiful woman in the world.” The dazzling pose was later replicated by an anonymous artist in the other, unnamed famous Sorel painting from the 16th century.

Despite Sorel being effectively reduced to that one exposed breast in art and memes alike, the evidence, as noted by medievalist Rachel E. Moss, that she actually dressed like this is scarce. Chastellain did accuse Sorel of being the “producer and inventor” of inappropriate styles of dress, which politician Jean Jouvenel des Ursins described as including “front openings by which one sees the teats, the nipples, and breasts of women.” But, as we already know, Chastellain was pretty salty about Sorel.

France’s first official mistress was much more than a “breast and crotch,” as one author described her.

The emphasis on her appearance has seen Sorel described by a medievalist as “France’s first bimbo.” Remove the blinkers, however, and her remarkable character and achievements reveal themselves. Not to be underestimated as mere arm candy, she indisputably changed the course of the kingdom.

Charles VII was, by all accounts, a pretty useless king. It was the latter part of the Hundred Years’ War and, in what Steenackers describes as “one of the saddest periods” of French history, just under two-thirds of France belonged to England and Burgundy. As for the nation’s finances, Steenackers wrote, “the king of France [put them] in the pawn shop.” He was too busy satisfying his “need for pleasure” in month-long frenzies of gambling, drinking and womanizing.

But, as soon as Sorel arrived on the scene, the king was a new man. “Charles VII,” Steenackers continues, “who, having already come to the age of 30, having understood neither his situation nor his duties, and having seemed destined for eternal mediocrity, reveals himself out of the blue and as if by magic.” Honest and able men, all friends of Sorel, took leading roles in parliament. In the space of two years, France was almost completely reconquered.

“Sorel urged the king to overcome his laziness,” wrote historian Henri Martin in 1855. “Charles finally became interested in his business and in applying his common sense and practical spirit to listening to useful advice and accepting, by hand, if not choosing, good instruments of government.” In fact, Sorel’s contribution to France was so instrumental that it has been placed by some historians as on par with that of Joan of Arc.

But, alas, it was not to last. When Sorel died in 1450, aged just 28 and pregnant with their fourth child, so did Charles’ glory. “All the weaknesses of his youth,” Steenackers says, “suddenly [overflowed] like a torrent which spilled its banks and spread out into scandals.”

Dysentery was Sorel’s official cause of death, but the widespread rumors of poisoning were finally confirmed by forensic scientist Philippe Charlier in 2005. Who orchestrated the poisoning? It is widely believed to be the work of the Dauphin (later Louis XI). The power-hungry man made it his life mission to undermine his father’s rule, and Sorel, who practically shared the crown, stood in his path.

It’s easy to be seduced by the popular image of the Dame de Beauté. But, whether or not she actually freed the nipple, France’s first official mistress was much more than a “breast and crotch,” as one author described her. As a result of her controversial position, her misguided adversaries, and most of all, her beauty, Agnes Sorel has not received from history all that she’s due.

It is poetry, by contrast, that does Sorel’s character most justice. In Voltaire’s The Maid of Orleans, she is both heavenly Venus and sage hero. But perhaps most fitting of all to her unhonored, behind-the-scenes power are these two lines from an old French soldier’s song: “We must go, Agnes orders it… Agnes gives me all the credit.”