Texas voters experiencing issues with voting machines used in that state have been told by election officials that they are the problem, not the machines. The state says voters are inadvertently touching the machines in ways they shouldn’t, causing the machines to alter or delete their vote in the hotly contested senate race between Republican incumbent Ted Cruz and Democratic challenger Beto O’Rourke.

But Dan Wallach, a computer science professor at Rice University in Houston who has examined the systems extensively in the past, told Motherboard in a phone interview that the problem is a common type of software bug that the maker of the equipment could have fixed a decade ago and didn’t, despite previous voter complaints. What’s more, he says the same systems have much more serious security problems that the manufacturer has failed to fix that make them susceptible to hacking.

Videos by VICE

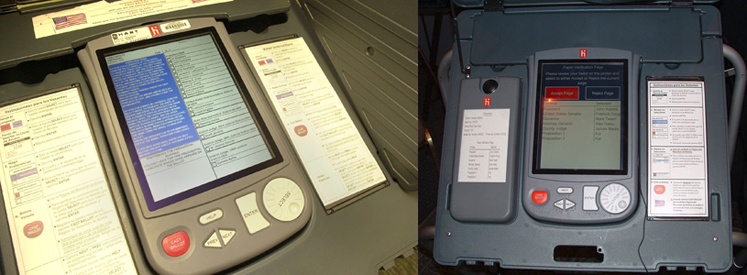

The problem involves eSlate voting machines made by Hart InterCivic—direct-recording electronic (DRE) machines that use a dial and button for voters to make their selections. Voters turn the dial in the lower right corner of the machine to scroll through each race and page of a digital ballot, and press the “enter” button, located just left of the dial, to make their selections.

The issue in the senate race has occurred when voters chose the option to vote a straight-party ticket—that is, to vote for only candidates from a specified party. Depending on whether the voter indicates they want to vote Democrat or Republican, the machine will automatically populate all races with candidates in the chosen party. But the multiple-page ballot can take several seconds to complete—in Houston the ballot runs 16 pages long. The Secretary of State and county election officials have blamed the issue on voters touching the machines while the systems are still rendering the ballot on screen—thereby inadvertently de-selecting their vote in the critical senate race. They say voters who touch the “enter” button while the system is still filling out the ballot can cause the machine to de-select their chosen candidate or change the vote to the other candidate in the race. Only between 15 and 20 voters—both registered Republicans and Democrats—have reported problems so far to the secretary of state’s office, though more may have experienced it without noticing, if they failed to review their ballots before casting them.

The issue is occurring primarily with the US Senate race because that’s the first race at the top of the ballot, Sam Taylor, a spokesman for the secretary of state told the Texas Tribune. The first screen voters see on the machines asks if they want to vote a straight-party ballot, and if they indicate they do, the next screen that appears is the first page of the multi-page ballot, already filled in by the machine with votes for candidates in the party they chose.

Leah McElrath, a freelance writer who specializes in political analysis, is one voter who experienced the problem in Houston. She waited 45 minutes in line to cast her ballot, she told Motherboard in a phone interview, and when she got to the machine, she selected the option to vote a straight-party Democratic ticket. She’s positive the first page of the ballot then showed a vote cast for O’Rourke because when she saw the machine highlight his name, she says she did “a happy dance” in her head. But when she got to the review screen at the end of the ballot, she saw that the machine had given her vote to Cruz instead. McElrath says she did manually change some of her selections on the ballot to Republican candidates after the machine filled out her straight-party choices—something the machine allows voters to do—but insists she didn’t do this in the senate race.

“They have literally … made zero changes on these machines,” Wallach said. “The software we are running today here in Houston is exactly the software that [we] looked at in 2007.”

She was able to easily change the vote back to O’Rourke before casting her ballot, but she was so concerned about the switch that before she did this, she took a picture of the review screen with her phone, showing the vote for Cruz. She didn’t report the problem to election workers at the time. “I didn’t want to be alarmist,” she told Motherboard, and she assumed it was a one-time anomaly, until she started hearing news reports that other voters had the same problem.

McElrath doesn’t buy the explanation from election officials that she and other users touched the “enter” button inadvertently and changed their senate votes. The button requires pressure to push and makes a slight noise when pressed like a computer keyboard, she said, making it less likely voters would press it without noticing.

Rice University’s Wallach said it’s possible the explanation by election officials is wrong and there is something else going on with the machines. When he voted in Houston on Saturday, he tried to reproduce the problem by selecting the straight-party option and quickly spinning the dial and pressing the “enter” button, but had no problem with the machine switching votes. A friend of his did the same and also had no issue.

But if election officials are correct that voter touch is the cause, Wallach says this is not a usability issue or a failure on the part of voters, but a software bug. The issue is a common problem in computer science known as a race condition or concurrency bug. It occurs when two things happen on a machine simultaneously that require the software to process at the same time. The two things essentially compete for the machine’s resources, as in a race.

“Ten years ago this was a known problem [with straight-party ballots]. And even then, years ago, we were told it was a usability problem”

“If the software was written in less than the most perfect possible way, then two things happening at the same time might step on each other’s toes,” Wallach said. In this case, while the machine is still populating the ballot with the straight-party votes, users are inadvertently touching the dial and pressing the “enter” button when the first page of the ballot containing the senate race is still loading. This causes the system to think they want to change the straight-party vote in that race to the opposite candidate, which is known as a cross-over vote.

Hart InterCivic told the Dallas Morning News that its eSlate system is not at fault and that the system “simply records the voter’s inputs; it does not, and cannot, ‘flip’ or ‘switch’ votes.”

But a well-designed system should not accept input from the voter while the machine is still populating a ballot. Wallach said that writing code to avoid race conditions is one of the hardest things to do in programming and one that nearly all students and even professionals get wrong.

“While you’re working on one part of the program, you have to be cognizant that this other thing might be happening at the same time. That is a very difficult thing to do, and as a result it’s very error-prone,” he told Motherboard. Nonetheless, he doesn’t believe Hart InterCivic or state officials should be let off the hook because they’ve had a decade to fix the issue and have chosen not to.

“Ten years ago this was a known problem [with straight-party ballots]. And even then, years ago, we were told it was a usability problem,” he told Motherboard.

In 2007, the Texas Democratic Party sued the secretary of state at the time because the eSlate machines failed to prevent voters from casting unintended cross-over votes on straight-party ballots. A Circuit Court struck down the case, however. Hart and election officials, recognizing that voters were having problems with the machines, could have altered the software to force voters to verify when they de-selected an already-selected candidate name that they really wanted to change their vote in that race, but didn’t do this.

In the 2016 presidential elections, a Texas voter reported the same problem with the machine changing her vote on a straight-party ballot as voters this month have reported.

The issue with straight-party ballots is not trivial, since 78 of the state’s 254 counties use the eSlate machines—for a combined population of about 7.2 million registered voters or nearly half the total number of registered voters in the state. And straight-party voting is a popular option for voters. It accounted for about 64 percent of votes cast in 2016 in the state’s ten largest counties, though the midterms this year will be the last federal election in Texas to allow straight-party voting. Lawmakers have voted to eliminate the option by October 2020. The same Hart machines, however, are also used in jurisdictions in three other states that allow straight-party voting—Indiana, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania.

Neither Hart, a Texas-based company, nor the Texas secretary of state’s office responded to inquiries from Motherboard before publication. Sam Taylor, spokesman for Secretary of State Rolando Pablos, told the Associated Press that the state “has no legal authority whatsoever to force” voting machine vendors to make upgrades to their systems as long as the systems are in compliance with federal and state law.

But Wallach says it’s not just the straight-party issue that Hart has failed to fix and that state officials have seemingly ignored. He notes that the company hasn’t released any new software at all for the eSlate system since 2007, despite a report he helped publish in 2007 showing severe security problems with the machines. Wallach, who conducted an extensive review of the systems for California and published the report with colleagues, says Hart has not fixed the problems in the intervening years.

“They have literally … made zero changes on these machines,” Wallach said. “The software we are running today here in Houston is exactly the software that [we] looked at in 2007.”

Wallach says the Hart eSlate DRE machines get networked together at polling places using a network port that predates ethernet. The machines communicate via this port, and HART also uses it to update software on machines, when the company actually updates software. But Wallach and colleagues found that the network interface is not secured against a direct attack, and they were able to read and write to the machines’ memory.

“If you can do that, that means you can read out all the votes or overwrite the votes or you can change the software,” he said. In their 2007 report, they wrote that they could do this not because of bugs in the Hart software but rather because of “features intentionally designed into the system which can be used in a fashion for which they were never intended.”

Because the machines are networked to one another at polling places, a hacker would need physical access to just one machine to subvert all machines at a polling place, he explained to Motherboard. But a hacker could also spread malicious code to all machines in a county from one machine. That’s because at the end of each election, all HART machines get taken back to the central elections office or county warehouse and get networked to a Windows PC running election-management software called SERVO (System for Election Records and Verification of Operations). The software does inventory management and post-election cleanup. But Wallach and his colleagues found a number of buffer overflow vulnerabilities in the SERVO software that would allow an attacker to take control of the SERVO system and use it to spread malicious code to every machine that connects to it. Buffer overflow vulnerabilities are basic programming errors that can allow malicious code to run on a machine.

“One machine can attack SERVO, and now an evil SERVO can attack every subsequent voting machine,” he said. Although the information about the SERVO vulnerabilities are ancient history, since they were first revealed in the 2007 report, it’s still relevant because “we’re still running ancient history [software] in our elections today,” Wallach said.

A hacker aiming to subvert a general election could corrupt one machine during the primary in order to alter all machines for the general election. Aside from a rogue insider who has direct access to voting machines, an external attacker could gain access to a machine in the days preceding an election when voting machines are left unattended in polling places or they could also subvert a machine during curbside voting. Wallach notes that Hart machines can be disconnected from the local network at a polling place and taken outside to allow disabled and other non-mobile voters to cast a ballot in their car.

“That’s a great accessibility feature, but it means you’re now giving this machine to someone in their car, with whatever tools they might have in the car, and giving them the privacy they need to vote,” he said.

It wouldn’t take an extensive amount of time to subvert a machine. “Many of these attacks can be mounted in a manner that makes them extremely hard to detect and correct,” Wallach and his colleagues wrote in their 2007 report. “We expect that many of them could be carried out in the field by a single individual, without extensive effort, and without long-term access to the equipment.”

Although election officials could check the hash of the software on machines to see if it had been altered—a hash is a cryptographic fingerprint of software that changes if the software changes—Wallach said a system that is already subverted can be programmed to lie about what code is on it and serve up false data that produces a hash that shows no changes have been made.

It’s not clear if the state and county officials have done anything to mitigate the issues uncovered in the 2007 report by Wallach and his colleagues. With regard to the straight-party voting issue, the secretary of state’s office has instructed counties to post signs telling voters to wait for machines to render their straight-party selections before doing anything else on the systems and to be sure to carefully review all of their votes before they push the final button to cast their ballot. But the Texas Civil Rights Commission, in a letter to the state on Friday, has called the measures “woefully inadequate.”

“The scale of this issue—in terms of numbers and geographic breadth—cry out for a statewide response from the only official capable of such action,” the Commission wrote. “Additional possible solutions to consider may include 1) an investigation into whether specific machines at polling locations are to blame, 2) sending additional technical assistance to counties and affected polling places, and/or 3) conducting an audit of or replacing problematic machines.”