Amid North America's worst drug overdose crisis in decades, Vancouver has cultivated two distinct and seemingly contradictory reputations.On one hand, the city's known to be ahead of the curve on progressive drug policy—always adopting the latest harm reduction practices and testing new addiction treatments. On the other hand, it's suffered more drug panics than any other Canadian city, and has a reputation for higher-than-average drug use and addiction rates. Vancouver is simultaneously a place the globe looks to for drug policy guidance, and a cautionary tale of recurring out-of-control epidemics.

Advertisement

Neither of these reputations are new, of course. Vancouver was the first city in North America to open a supervised injection site in 2003. And its history of drug panics spans a full century.This has led many outside Vancouver to assume new drug policy developments are somehow a contributor to the crisis—that safe injection sites and similar harm reduction practices actually encourage more users. But if you ask the doctors and researchers who have been studying the city's drug waves for decades, this is a categorically false narrative that goes against a near century of history. Experts told VICE Vancouver has long been an international drug distribution hub, and that reactionary criminalization efforts, as well as failing social policies, have created a concentrated underclass of marginalized drug users."Vancouver has always had a high diversity of drugs and a potent supply of drugs," Dr. Thomas Kerr, associate director of the BC Centre on Substance Use, told VICE. Kerr says many port cities around the world are known for "alarming" levels of drug use, in part because the dope is so strong."I know for example I published a study around 2003, and at the time the available data from RCMP labs suggested cocaine in Vancouver was something like 40 percent more pure than the cocaine seized in Western Europe."Kerr says heroin and cocaine in particular often arrive in Vancouver first from drug-producing countries. "What happens, I think, is that often when the drugs arrive here, they're in their most potent form, and as they make their way to distribution networks throughout the country, they increasingly get stepped on, as they say—other fillers are added, and the potency tends to be reduced."

Advertisement

This potency theory might partially explain why drugs have had such a devastating impact on Vancouver, but Kerr admits it isn't the whole story. Why, for example, hasn't Seattle also become "ground zero" for opioid overdoses? (Seattle, it turns out, is quickly catching up to Vancouver, with a record-setting 345 deaths in 2016. Between 2012 and 2016, Metro Vancouver including Surrey saw 1,031 ODs, compared with 995 in Seattle.)To understand how we got here, according to University of Guelph researcher Catherine Carstairs, you have to look back to Vancouver's first recorded drug panic in the 1920s. Drugs like morphine, cocaine and opium got an early start in the city before any of these were ever made illegal because of its position as an international port. "The supply chains were established and they kept coming," says Carstairs, the author of Jailed for Possession.Carstairs told VICE Canada's early drug prohibition laws grew out of a xenophobic panic rocking the West Coast. At the time "opium dens" were breathlessly reported as a scourge on (white) society, and politicians brought in laws that basically aimed to punish and ostracize the Chinese. Police began raiding dens and deporting immigrants. "The drug panic was not so much about the drugs and really about finding an excuse to keep the Chinese out of Vancouver," Carstairs told VICE. Emily Murphy of Maclean's, one of Canada's best-known writers of the era, painted Chinese people as villains somehow taking advantage of white "victims." At the time, Carstairs says media played a "huge" role in creating a sense of panic, demonizing drug use along the way. "The Vancouver Daily World was clearly selling papers on the drug panic it created," Carstairs told VICE. "It featured drug stories on front pages for weeks on end."

"The drug panic was not so much about the drugs and really about finding an excuse to keep the Chinese out of Vancouver," Carstairs told VICE. Emily Murphy of Maclean's, one of Canada's best-known writers of the era, painted Chinese people as villains somehow taking advantage of white "victims." At the time, Carstairs says media played a "huge" role in creating a sense of panic, demonizing drug use along the way. "The Vancouver Daily World was clearly selling papers on the drug panic it created," Carstairs told VICE. "It featured drug stories on front pages for weeks on end."

Advertisement

By the 1930s, white people were a much larger portion of the drug-using public—thanks in part to the deportation and imprisonment of Chinese users—but government compassion for users did not follow. All users faced harsh minimum sentences, even years of jail time for possession of trace amounts. According to both Kerr and Carstairs, these heavy punishments served to create a class of drug users who could no longer hang on to regular jobs or contribute to regular society. Instead they cycled in and out of jail, learning better ways to access drugs along the way.Between 1946 and 1961, more than half of all narcotics convictions in Canada were happening in Vancouver, compared to 24 percent in Toronto. "Because we passed such incredibly harsh laws against drugs, and police were busy enforcing them, it really worsened the lives of drug users," Carstairs told VICE. This wave of enforcement solidified an underclass of drug users unable to free themselves from poverty or addiction.Through the 50s and 60s Carstairs says drug overdose deaths were surprisingly rare. It would be decades later that opioids became potent enough to kill a person. Addiction was chalked up to personal responsibility, and treatment was not even a remote option.Meanwhile, Vancouver was gaining a reputation as an "edge of the world" according to Carstairs—a counter cultural hub that some sought to escape responsibility. "If you look at stats from the 50s and 60s, you see divorce rates and illegitimate pregnancy rates were higher," she said. "People who were of a more alternative or experimental mindset worked their way out there."

Advertisement

From there, Vancouver's approach to housing its low-income residents begins to play a role in creating epidemic conditions, according to Kerr. "The fact we have this large network of low income housing that was originally developed for seasonal workers, and over time became homes for the urban poor and the deinstitutionalized mentally ill population, it just created a bad situation," he said.The Hastings Street drug market first served a high concentration of transient workers in the 1950s, and later an entrenched homeless and low-income population. Kerr says there's been as many as 5,000 injection drug users living in a few block radius. Meanwhile, cops had a mandate to shake down suspected users at every turn.Kerr says homelessness and similarly horrific housing conditions can encourage riskier drug use behaviour. "If you take a population at risk, put them in substandard housing, criminalize them, and you throw police at them, you tend to make a drug problem worse, not better."

Even as drug use centralized in one low-income neighbourhood, there was still very little talk of treatment in BC. Carstairs says the first solution floated by the government is opening a "treatment prison."Then came the deadly drug waves of the 80s and 90s—something Kerr has studied closely. Opioids were not the only drugs ruining lives through these years—cocaine, crack cocaine and methamphetamine all caused panics of their own. "In the early 90s people were predominantly ingesting heroin," he said. "There was high potency heroin available because that prompted chief coroner of the province to create a task force looking into the issue of opioid overdose in the province, and in part informed the public health emergency that was declared."

Advertisement

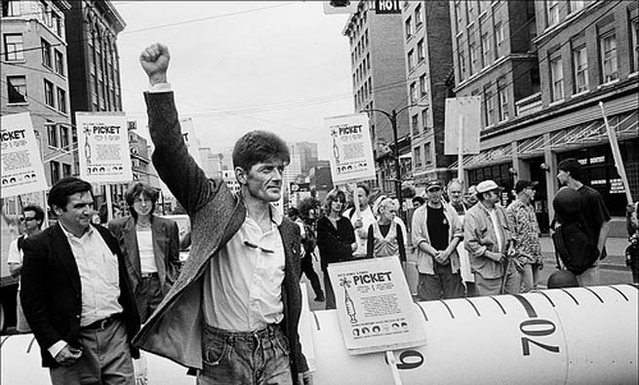

Police crackdowns continued well into the 90s era as authorities raided "problem premises," revoked business licences and even imposed a curfew on the Downtown Eastside neighbourhood. Policing in other neighbourhoods pushed street homeless people to further concentrate in the neighbourhood, while low-income housing options in the country's most expensive city continued to evaporate. Kerr says the social conditions were ripe for more drug waves to come."The next real big wave occurred in mid-90s, when the arrival of powdered cocaine showed up in Vancouver," Kerr told VICE. He says cocaine injection was what truly kicked off the HIV epidemic in the area, which became the focus of a public health emergency in the late 90s. "This was a real challenge because at the time, while Vancouver had needle exchange operating, it was really designed for heroin users," he said. "Although heroin users typically inject two or three times, cocaine has a much shorter half life, therefore it's not uncommon for people to inject 10, 15, 20 times a day, to go several days without sleep and then crash for days."It's worth noting harm reduction resources like needle exchanges were not first introduced on compassionate grounds. Carstairs says political support for these programs originally came from fear of spreading HIV to the rest of the population—not necessarily from improving the lives of users. Drug users were literally labeled a contagion.

Advertisement

Kerr's team was tasked with containing the spread of disease. "The volumes of needles they were giving out were nowhere near adequate to cover the number of injections cocaine users were doing. That led to very high levels of syringe sharing, difficulties accessing syringes locally and high rates of hepatitis seen as well.""In the wake of that, we saw declines in powder cocaine injection, we saw a rise in crack cocaine use," said Kerr. "Everyone was smoking crack cocaine and the public health system wasn't ready with this as well… We were surprised to find in our own work that among people in our studies, crack users were more likely acquiring HIV infection. That came as a bit of a surprise because they were mostly inhaling drugs, but a lot were injecting too.""Shortly after the big crack wave came, we also documented a large rise in crystal methamphetamine injection. Including among young people," he said. "If you stand back and look at this recent history, what's really striking about it is the diversity of drugs."All of these drug panics came and went without the province of British Columbia enacting a comprehensive user-focused addiction treatment plan, according to Kerr. And it wasn't until the 2000s that cops began winding down the War on Drugs approach. "Police have been more progressive of late, and are now supporters of evidence-based treatment, but historically in the 90s, even up to 2003 they were trying to do things like police crackdowns—none of which worked, it actually fueled high-risk behaviour."Though all these panics, study after study has proven harm reduction is not to blame. "It's really frustrating listening to people offering non-evidence based studies, which often happens in case of harm reduction. Intuitively it makes sense—if you provide a syringe, you're enabling drug use," said Kerr. However, a scientific evaluation of Insite found supervised injection sites increase the number of treatment and detox admissions.Looking back at this history, Kerr says harm reduction programs succeeded at containing the spread of needle-borne disease (HIV rates are now below one percent), and reduced overdose deaths, but failed to medically address addiction. "You can't tell this story without acknowledging we have been totally lacking an effective system of addiction treatment, and it's been like that for a very long time," said Kerr. "We've gone from saying the system is broken to saying there is no system."Kerr says that decades of criminalization have pushed Vancouver drug users further from the health system, which left Vancouver especially vulnerable when fentanyl and other synthetic analogues hit the illicit market. "It's hard to simultaneously criminalize and provide services. If you're engaging in illegal behaviour, do you really want to go into a healthcare provider and get treated like crap?"Though attitudes are shifting, Carstairs agrees that stigma is ultimately what fuels Vancouver's entrenched drug problem. "They're still pariahs of our society. I think the laws we put in place, even though they've been significantly changed, established a culture of seeing drug use as a criminal matter rather than a health matter." On that front, there's now a full century of evidence.Follow Sarah Berman on Twitter.