We’ve all been there. It’s 2AM, you’re in a sweaty, packed-out basement club and you’re starting to feel the first flutters of that pinger you popped 20 minutes ago. Then someone puts “Let Me Be Your Fantasy” by Baby D through the speakers. You become convinced – more convinced than you ever have been of anything in your life – that it’s the realest, most heartfelt and, actually, now you think about it, genius song that’s ever been written. How can it be so sad yet so happy at the same time? Who dreamt up such an entrancing, euphoric melody? The lyrics are speaking to you on a visceral level. You’ve listened to it before, but you’ve never really listened to it before, do you know what I mean? You begin to weep. A few tiny, happy tears at first. And then big, ugly ones. You’re screaming now. Screaming, on the dancefloor to Baby D.

Ecstasy and acid house are so intertwined, they’re practically indebted to each other. Without thinking about it too deeply, it makes a lot of sense. How can you truly connect with the bittersweet piano plonks of Liquid’s “Sweet Harmony“, for instance, if you’ve never got so rushy on MDMA you could cry with delight? Have you heard the chorus of Black Box’s “Ride on Time“? It’s practically someone shouting with irrepressible joy – and it’s hard to achieve such a feeling unless the serotonin receptors in your brain have been amped into overdrive with the help of this particular substance. You wouldn’t listen to aggressive industrial metal after popping a pill, would you? No, you’d listen to something uplifting, something with feeling.

Videos by VICE

It’s not just MDMA and acid house, though. Other drugs and genres have also historically bolstered each other in very specific ways. From the link between jazz and heroin in the 1960s, to mushrooms and psychedelia in the 1970s, to disco and quaaludes, to reggae and weed, to punk and speed, to hip-hop and lean, to rap and coke or shoegaze and acid. But why exactly do certain genres of music go hand-and-hand with certain drugs? And how much of this is cultural versus purely biological?

Dr Zach Walsh, an associate professor at the University of British Columbia’s Department of Psychology, has done a bunch of research on the subject and says there are a variety of factors at play here. The first being, quite simply, that good things go well together. “It’s partly down to what I call the ‘peanut butter effect’ where chocolate is good, and peanut butter is good, so you combine them and it’s good together,” he explains.

But, according to Walsh, it also has a lot to do with what is referred to as the locus coeruleus – AKA the “novelty detection” part of the brain – and how that responds to both music and drugs. “If we think about what makes music engaging, we want familiarity, but we also want novelty. So what some drugs will do, particularly if we’re talking about psychedelic drugs, is activate and enhance the part of our brain that detects ‘novelty’, meaning that part of the drug experience is like ‘oh my god, I’ve never seen the world this way before’. So when you hear music on drugs, you have the experience of it being entirely new, like you’re hearing it for the very first time.”

If you’ve ever gotten high and rediscovered an old album, Walsh’s words will ring extremely true. Ever been up at 6AM, still buzzing, and decided to swipe the aux cord from someone’s vice-like grip so you can play “I Wanna Be Adored” again? That’s because your brain thinks you’re hearing it for the very first time, so it feels extra meaningful and exciting. As well as this, Walsh says, drugs can allow the brain to concentrate in a way that it doesn’t usually, meaning that you can focus on the music without distractions, enhancing your experience of that music. “There’s a long history of cannabis and meditation and yoga etc, for instance,” Walsh says, “so it induces a more mindful, focused state. So you can be less distracted by cognition based on the past and the future – you then appreciate the music more. There’s also the sense of disinhibition that comes with drugs. So there’s the novelty appreciation, the ability to focus on the present and then there’s the general disinhibition.”

This is all well and good, but why exactly do certain genres go so well with certain drugs? What’s that all about? Walsh says this question is a lot harder to answer, but we can hypothesize. “There are probably a lot of cultural factors involved,” he tells me. “People who make certain types of music have certain drug experiences, and then people who listen to that music are influenced by it, so it’s a chicken or egg situation. Culture feeds into biology and biology feeds into culture.” It also has a lot to do with functionality. “When it comes to improvised music, like jazz or reggae, that enthusiasm for surprise might come from a lot of cannabis,” he adds. “And drugs [like MDMA] facilitate dancing, which goes with the energetic, repetitive physical aspect of certain genres.”

Harry Shapiro, author of Waiting For the Man: The Story of Drugs and Popular Music, echoes the notion that the the association between various drugs and particular genres is related to both functionality and culture. “If you’re part of an all-night dance culture – whether it’s mods in the 60s or rave culture in the 90s – you’re going to want to stay up all night, and the best way of doing that is to take some kind of stimulant like ecstasy,” he explains. “On the other hand, if the whole idea of the genre of music is to be more static and introspective, then you’re more likely to want to take more psychedelic drugs such as LSD, mushrooms and cannabis.”

In some cases, though, Shapiro argues that the pervasiveness of certain drugs among certain genres is more complex. “Sometimes it’s not necessarily the style of the music, so to speak, but where the musicians who made it were coming from,” he says. “In the 50s and 60s, heroin was a big part of bebop jazz and it wasn’t considered cool to be into dance music. It was more about being cool and detached. So heroin was part of the culture. As well as that, it was a way of dealing with being a black musician in a white racist society. So there isn’t just one answer to the question – it’s psychological, cultural and it’s functional and creative.”

So, on the question of why hoovering up some lines before rapping the entirety of Tupac’s “Hit Em Up“, twice, is such an enjoyable pastime (if you’re into that kind of thing), or why “Promised Land” by Joe Smooth simply sounds better on pingers, there is no simple answer. As Walsh said, biology feeds culture feeds biology feeds culture, so it’s difficult to draw definitive lines around something so amorphous. That said, the link between the two can be best explained as a symbiosis of brain functions and culture that intertwine and inform each other. But also, when your jaw is swinging and your arms are flailing on the dance floor under a sea of multi-coloured lights, does it really matter how you got there, or why?

You can follow Daisy on Twitter.

(Lead image by the DEA via Wikimedia)

More

From VICE

-

Collage by VICE -

-

Collage by VICE -

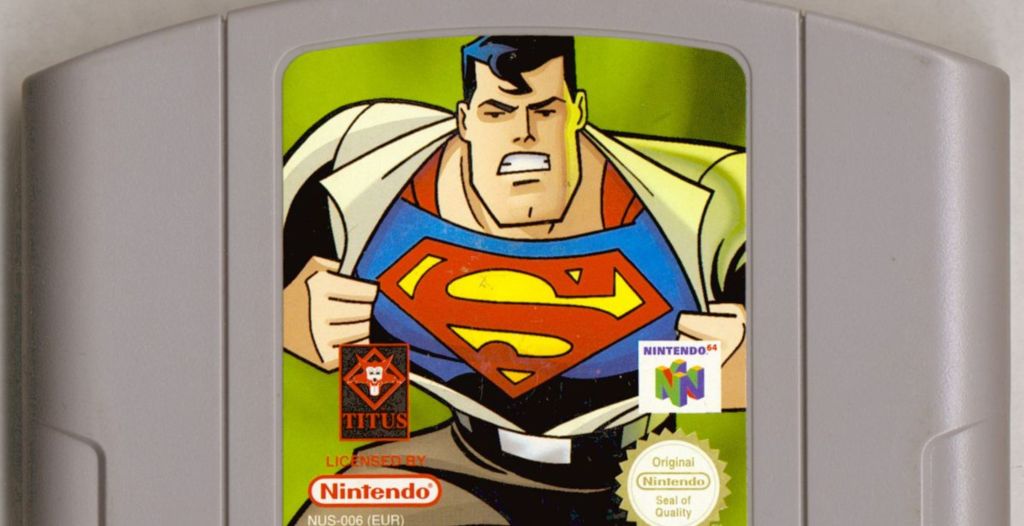

Screenshot: Titus Interactive