Illustration by John Garrison

Under the Covers explores the stories behind iconic album covers.

Videos by VICE

Anyone who knows Andrew W.K. personally will tell you—if there’s anything he loves as much as partying, it’s playing pranks. For years, the greasy party rocker has gleefully fanned the flames of an online conspiracy theory about himself that claims that he is not the original Andrew W.K., but an actor hired to replace the man who initially portrayed him. He has also subtly and not so subtly enjoyed the occasional trolling of interviewers and news anchors. Not to mention, some people have hypothesized that his entire existence is one elaborate piece of Andy Kaufman-esque performance art. So when pressed on the circumstances that led to the iconic image of his nose dripping blood on the cover of his breakout 2001 album, I Get Wet, he gets a bit dodgy with details.

“After years of talking about it—and it’s not due to me being tired of talking about it at all—I don’t want to say how I did it,” he tells me. “I feel a little bit bad about it. It’s not something I want to encourage others to do. It’s not something I would want to do again.”

In past interviews, he has given varying accounts of the photoshoot behind it. He has claimed to some that he took a chunk of cinderblock and rammed it into his face to produce blood. He has also said that since he was unable to produce enough blood through force, he squirted his nostrils with pig’s blood that he got at a butcher shop.

Even the image’s photographer, Roe Ethridge, seems to be in on this charade when pressed. “Andrew went into the bathroom, he did… what he did, and he came out with blood coming out of his nose,” he says diplomatically, carefully navigating his word choices for this corroboration, all these years later. Ethridge hasn’t kept in close contact with W.K. over the years, he says, but he was instantly drawn to him upon meeting him.

“When I meet somebody, it doesn’t take long to realize if I’m going to like them. It’s minutes. And Andrew, I liked him immediately,” he recalls. In 1999, Ethridge was an up-and-coming name in the art world, doing photography commercially and for galleries. On the side, he was the official photographer for New York electropop duo Fischerspooner. It was at one of their shows, a daytime performance at the Astor Place Starbucks in Manhattan where W.K. and his keyboard were the opening act, that the two met.

“Andrew was such a character,” remembers Ethridge. “I was immediately like, ‘Who the fuck is this guy? I love this guy.’”

Just after W.K.’s 20th birthday on May 19 while performing with Fischerspooner on the 107th floor of the World Trade Center, W.K. somewhat brazenly asked Ethridge to shoot the cover for his upcoming debut album.

“He didn’t know me in terms of being friends, he didn’t owe me any favors,” says W.K. “I may have been annoying to him, considering I was quite young.”

Ethridge agreed, and set up a shoot at his loft at 85 North 3rd Street in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, in a building that now houses luxury condos and upscale boutiques amidst a constantly gentrifying neighborhood. W.K arrived and got situated in front of Ethridge’s large-format, four-by-five camera, and had a very specific vision in mind.

“He said he was going to get an axe at the hardware store,” laughs Ethridge. “And I was like, ‘Okay, that’s cool. Whatever you want to do, man.’ And apparently he couldn’t get an axe. But he was very specific about what he was going to wear, how it was going to go, about what he was going to look like. He was self-styled.”

“I said I wanted a black background, and I wanted the lighting like a movie,” says W.K. “It was very refined and cinematic. It was clear and dramatic, not natural lighting, but very commercial and artificial. There’s an intention in this photo.”

The camera required a good amount of prep time for each shot, so they took only a few photos where W.K. was making extreme poses, “cartoon horror faces” as Ethridge describes them. Then W.K. had one more idea he wanted to try out. He excused himself to use the restroom where something happened, and he emerged minutes later with blood dripping out of his nose, over his lips, and all the way down his neck to his plain white t-shirt.

“[Ethridge] is a very reserved and mild mannered person. He didn’t really react at all,” says W.K. “I don’t remember him saying anything. I didn’t get the sense whether he liked it or not.”

A weird stroke of artistic magic happened after that. Ethridge gave W.K. one very small, very obvious direction that changed the course of the shoot and really, the course of W.K.’s entire career—don’t do anything. Stop making intense faces and just look straight at the camera. This, he hoped, would render a strong juxtaposition between the extreme visuals of his bloody chin and a neutral, expressionless stare.

So W.K. sat there blankly under the lights, looking straight through the lens, with his mouth slightly agape and strands of wet, dark brown hair over his dead eyes as red drops hardened against his skin. Ethridge framed the shot and snapped two clicks of the camera, one of which ended up producing the image that would become the cover of I Get Wet. “A total fluke,” as W.K. describes it.

There’s a striking, hypnotic quality to the cover of I Get Wet. It’s almost completely devoid of color and action, drawing your eye directly to the red blood against W.K.’s light skintone. Dave Grohl once described it to Interview as “the sexiest thing you’ve ever seen in your life” and remembered hating it initially because his girlfriend immediately developed a crush on W.K., but he was soon blown away by the music and fell in love himself.

Although W.K. was pleased with the result, not everyone else was as thrilled.

“My A&R guy thought it would pigeonhole me,” says W.K. Many people at his American label, Island/Def Jam, thought that the image, combined with the potential single, “Party Hard,” would forever label him as “the party guy.”

“I was like, ‘that’s the whole point!’” he says. “I wanted to be like Santa Claus. I wanted to have a logo, something that was perpetual and consistent. I was not—and am still not—interested in evolving or abandoning things or changing. I want to build something that sticks.”

W.K. had a vision for his brand early on and was meticulous in implementing it. In Phillip Crandall’s 33 ⅓ book about the album, Island art director Scott Sandler recalled, “I don’t think I had ever worked with anyone who knew exactly what they wanted. He provided a manifesto, like a book. Like, ‘I like this font. Centered black background.’ I had never seen anything like that. I feel like with any genius, there’s an element of crazy.”

In England, where the album was initially released, the bloody nose image was plastered on billboards all over the country, drawing enough complaints from citizens, many of whom interpreted it to be advocating cocaine use, for the Advertising Standards Authority to intervene. The album’s UK label, Mercury Records, was ordered to remove them after the ASA said they could frighten “children and vulnerable people,” which was ridiculous to W.K., because “who hasn’t had a bloody nose?”

It didn’t fare much better in the US. W.K. recalls a huge meeting in a conference room at the Island offices, where there was an air of apprehension. Many distributors were reporting that big retailers like Walmart and Best Buy wouldn’t display the album because of the blood. The label had to break it to W.K. that the cover would have to be censored with a giant black sticker over the front. They were expecting this to be crushing news to W.K., who had carefully plotted every detail of the album, from its unified wall of sound recordings to the font spacing of his name on the front. But, to their surprise, W.K. was elated.

“I said, ‘Don’t you realize this is the greatest thing that could ever happen? If we put a sticker over the blood, it’s just going to make something want to see what’s under the sticker!’” he remembers.

His prediction was accurate, and the album went on to become a megaseller for the label. It also catapulted Andrew W.K.’s celebrity, making him a household name as his unapologetically loud style of rock tapped into the country’s post-9/11 cathartic need for mindless headbanging. Some critics were unphased—Pitchfork dropped an abysmal 0.6 on it, calling it “tard rock,”—but that didn’t stop him from amassing a rabid, international cult following, one that continues to this day.

The bloody nose has become synonymous with W.K. and his relentlessly positive, pro-partying message. A near endless list of variations of the design have been printed on merch items, both official and unofficial, from t-shirts to bandanas. It has inspired fan art and tattoos across the world, and has become the go-to costume for lazy music fans. With just a few drops of blood and a love of partying, anyone could be Andrew W.K. He has become less of a singular person and more like a universal symbol, one anyone could adopt. It’s exactly what he wanted.

“The fact that people integrated it into their own life, whether it was wearing a t-shirt or dressing up as it for Halloween, is amazing,” he says. “I wanted it to be as recognizable as possible, but also easily replicated. I wanted to make it so everyone could be this. I could be this, and they could be it—this feeling.”

When reminded that 15 years have passed since I Get Wet‘s release, W.K. seems taken aback, and starts reflecting on it as if it were some act of fate, a prophesy that he was powerless in fulfilling.

“You sort of turn yourself to other forces at work, a blind destiny that you are a slave to, and that has pulled you all along. It’s very hard to take credit for this, no matter how directly I thought I was causing it. It’s too absurd and unlikely of a thing to happen to take credit for. I’m just trying to be strong enough for these opportunities that seem like they want to exist.”

And it all happened because the stars aligned when a photographer instructed a weird guy with a mysterious bloody nose not to move.

“It’s like that Eastern religion sort of thing, you know?” says Ethridge. “All you have to do is bend the blade of grass and then the whole fucking world changes.”

When it’s time to party, Dan Ozzi will be on Twitter – @danozzi

More

From VICE

-

Photo: Jorge Garc'a /VW Pics/Universal Images Group via Getty Images -

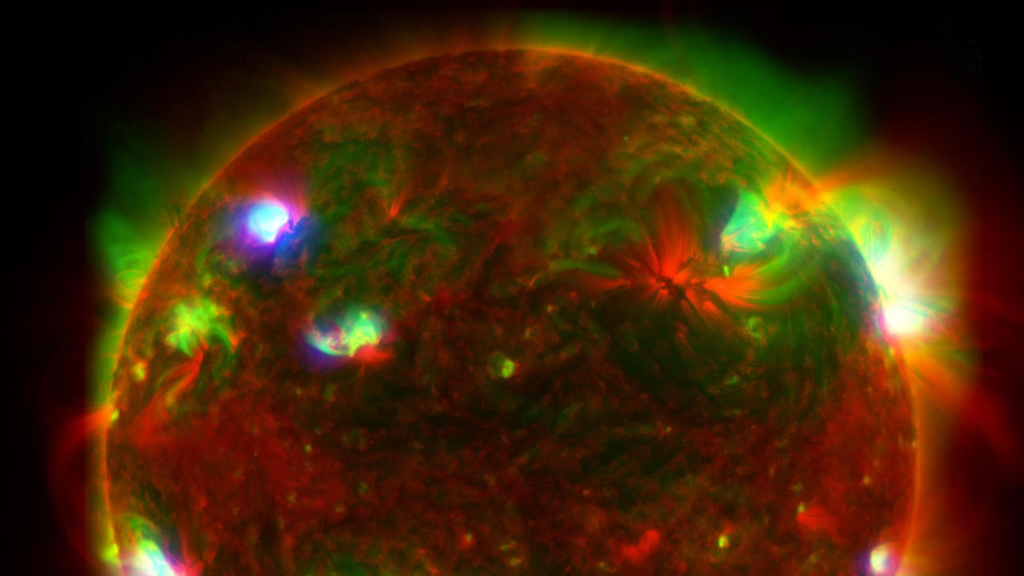

Three-Telescope View of the Sun. Photo: NASA -

Photo: Maria Teresa Tovar Romero / Getty Images -

Photo: grecosvet / Getty Images