A still from ‘Northern Soul,’ a new film from director Elaine Constantine

Northern Soul changed English club culture forever. Instead of venue owners recruiting cover bands to slog through a set of Perry Como covers, young Britons began to take control of their nightlife, hiring out clubs, booking the DJs, and recruiting guys in brogue shoes and bowling shirts to master the speed that kept everyone dancing all night.

Videos by VICE

Elaine Constantine is a photographer and filmmaker who grew up in the Northern Soul scene. Tomorrow marks the UK release of her film, Northern Soul—which tells the story of two working-class boys and their experience of soul music, love, drugs, and death—so I thought I’d call her up for a chat.

VICE: A lot of the film is based on your experiences, right? Do you remember the first time you heard a Northern Soul record?

Elaine Constantine: I grew up in a large industrial town called Bury, on the outskirts of Manchester. I went to this massive youth club, which was in the town hall, and I remember hearing this weird record come on. It was quite strange sounding—a bit old fashioned, with lots of reverb, and just really heartfelt.

Suddenly these guys came out on to the floor and cleared it.They were doing fast spins and high kicks and drops and this amazing footwork, but they were each dancing on their own and they were locked into the track. Normally when you’d see boys dancing it would be to Status Quo, with a denim waistcoat on, and doing the air guitar. These guys were so amazing; it was such a spectacle. I just thought, Oh my God, what is this? And then my older cousin said to me, “This is Northern Soul.”

Elaine, left, with her then boyfriend Rob in the early 80s

British singer Tracey Thorn has argued that Northern Soul was primarily a masculine movement. How does that relate to your experience?

A lot of people have asked me why I haven’t done a women’s story of Northern Soul, but I wanted it to be very real—a truthful representation. Men collected records. Men wanted to be DJs. The people who took the roles in driving the music forward—the DJs, the promoters, the collectors, and the drug dealers—were all mostly men. But then that doesn’t mean there weren’t a lot of women following it, and collecting, and driving that dance floor passion. So I’d say it was kind of 50/50, but that the main movers and shakers were men.

You’ve said that you wrote the script about observations of young men you knew “collecting vinyl, dancing, DJing, taking drugs, and generally being degenerates.” Can you tell me a little bit about the real people behind your characters?

The two main leads are based on my experience of being married to a DJ, my husband—who I met when I was 30—and my first boyfriend, who I was engaged to and was with for years, but who is unfortunately dead now. I was absolutely in love with him. He was the whole package. He was the most amazing dancer you could ever see: he had the rhythm, he could do the acrobatics, he looked amazing, he dressed amazing… you know, he was the coolest guy I had ever met in my life.

I kind of based the character Sean on him. I remembered watching him floor three big guys right in front of me without warning: Bam, bam, bam! That fight scene in the film is from my own real experience, and when the lead, John, goes, “Oh, I didn’t have time to react,” that was me, because I felt bad that I hadn’t helped him.

A still from ‘Northern Soul’

How did soul music first infiltrate British culture? And why do you think black American music took off up north ahead of down south?

Well, I think a lot of white musicians from the 1960s, like the Stones, got into blues mainly because they wanted to listen to more authentic music than what was in the pop charts, and the BBC wouldn’t play American music. So they had this tradition of finding black music that was real and earthy, and that became a staple throughout the 50s and 60s. That’s how the mods evolved; they were into the blues, R&B, reggae, and stuff like that. And then the younger siblings became the suedeheads and the skinheads. Northern Soul was just an offshoot from that.

I think it developed specifically outside of London because, by the late 60s, psychedelia had caught on big with people down south and the middle classes. But hippie culture totally didn’t appeal to the working classes. They wanted to look smart when they went out on weekends, because they’d looked like shit all week, in the factories or the mines or whatever. They were hitting on soul music because it felt more real.

There was also the fact that the media—like NME, for example—was driving the music output in London, and all the music magazines were pushing popular acts. So London was caught up in the modern-day music of the time, and soul was being embraced by the suedeheads, the skinheads, and the post-mod communities.

Yeah, you get the sense in the film that there was a lot of giving the finger to the status quo.

Yeah, there was definitely a real sense of snobbery about the charts. The ethos was, “I’m not swallowing that. I’m doing my thing.” That might have been a sort of trade union spin off or something, but it bled into the subculture in a big way.

Elaine with friends in the early 80s

How do you think Northern Soul played into modern club nights as we know them?

In the 50s and 60s, prior to the Northern Soul scene, a lot of the big events that people were going to on Saturday nights would be either a band covering popular chart music, a DJ that the brewery or license company had hired to come in and play popular music, or stuff like waltzes. When Northern Soul happened it was the first big club culture where the actual punters took control of the night, so they hired the venue and they put on the DJs. So it was the first example of how we understand club culture today, where these promotions are put on by the people who are directly involved in the scene rather than official organizations.

In the film, the main excitement stems from discovering new songs that haven’t been heard before, which were sometimes called “cover ups.” Can you tell me a bit about that?

Back then you’d have a DJ or record collector, and they’d go to America and find a track that they knew wasn’t in the scene yet. Let’s say the guy selling them says, “OK, there’s only five of these records. I have three and there’s another two floating around somewhere.” The collector will buy all three, cover up the title on each record with a white label and call it something else. So no one knows the real name of the record; he’s the only person who has possession of that song.

If that song’s good—if it fills the floor—then it becomes that DJ’s song: it’s his cover up. And everyone knows it’s a cover up because they can’t see the label, and everyone’s looking at the decks the whole time. And then if someone finds one of those other two records, then the DJ is exposed, and the song is known by it’s original title from then on.

An exclusive trailer for ‘Northern Soul’

Are you hoping the film will revive an interest in Northern Soul? This sense of what’s important about music: the lyrics and the passion behind it.

I don’t want to get all moral on it because people just do what they do and like what they like. It’s not up to me to dictate. But if you think about it, what’s not to like about Northern Soul? I was listening to the radio the other day and there’s this guy singing, “I think I want to marry you.” And I just thought, Why the fucking hell do you think that? Why even write about it if you only think that?

Then you put a record on by someone like Johnny McCaul, from the Northern Soul vault, and it says stuff like, “I’d like to hold you tight / baby you’re my guiding light / like holding on to my last thread of life / scald my hand to make me understand I need you.” I mean, there are fucking lyrics like this out there and people want to listen to that Bruno Mars shit. I mean, “I think I want to marry you”? How long did it take the guy to come up with that line? If you only think it, then why mention it? Why even write it in a record?

Northern Soul is out tomorrow, Friday October 17

Follow Georgia Rose on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

Photo by Timothy Norris/Getty Images for Coachella -

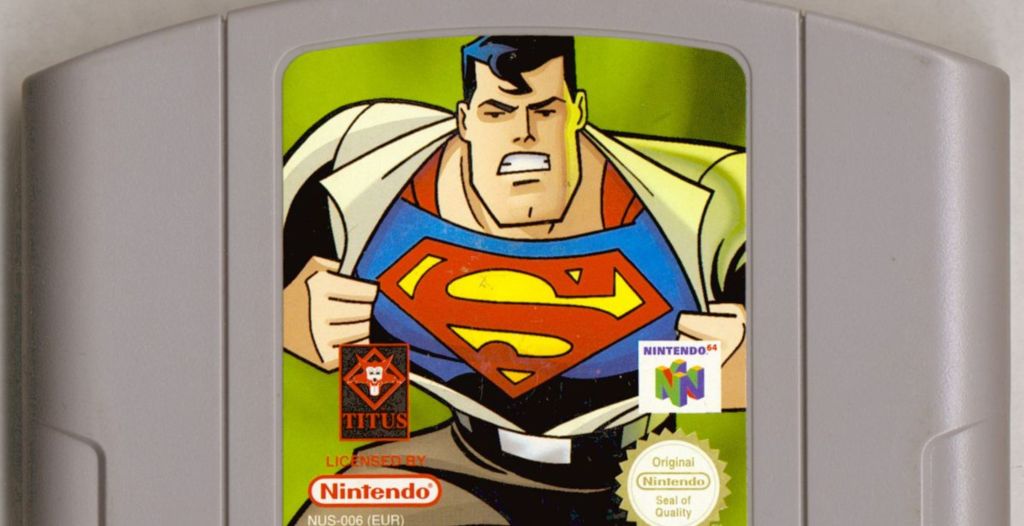

Screenshot: Titus Interactive -