In our Dancing vs. The State series, THUMP explores nightlife’s complicated relationship to law enforcement, past and present.

It sounds like it belongs on a list of weird, obsolete laws in America, alongside the Alaskan statute against giving a moose a beer or Idaho’s allowance for cannibalism in life-or-death situations. But New York City’s cabaret law, which bans three or more people from dancing in a club or bar that lacks a special license, is a strange old law that is still very much in effect.

Videos by VICE

Under the cabaret law, owners of establishments that wish to allow dancing must apply for a special “Cabaret License” through a notoriously difficult process. Before the license is granted, applicants must jump through several bureaucratic hoops, like seeking approvals from the building and fire departments, installing surveillance cameras, and paying fees ranging from $300 to $1,000. As of last year, according to the city’s department of consumer affairs, only about 127 of the city’s more than 12,000 clubs and bars actually have cabaret licenses.

Unique in the nation, though similar to prohibitions on dancing in some other parts of the world, New York’s cabaret law has been on the city’s books for nearly a century. It was introduced under Mayor Jimmy Walker in 1926, with the goal of making it easier for police to control speakeasies and clubs that were illegally serving alcohol under Prohibition. Since then, the law has gone unenforced for long periods, been amended several times, and become a focus of furious political conflict—but it has never been repealed. As a result, its use by the authorities to enforce institutional racism and classism has become a sort of secret history of New York nightlife.

According to a 1987 article in the New York Times, the cabaret law was meant to ensure fire safety, enforce occupancy limits, and monitor the moral character of club owners. However, the original legislation not only banned dancing in unlicensed clubs, but also limited permitted instruments to strings, keyboards, and electronic soundsystems—leaving out jazz staples like wind, percussion, and brass. In addition, it prohibited more than three musicians from playing at one time—provisions that impacted Harlem jazz clubs and jazz bands the most.

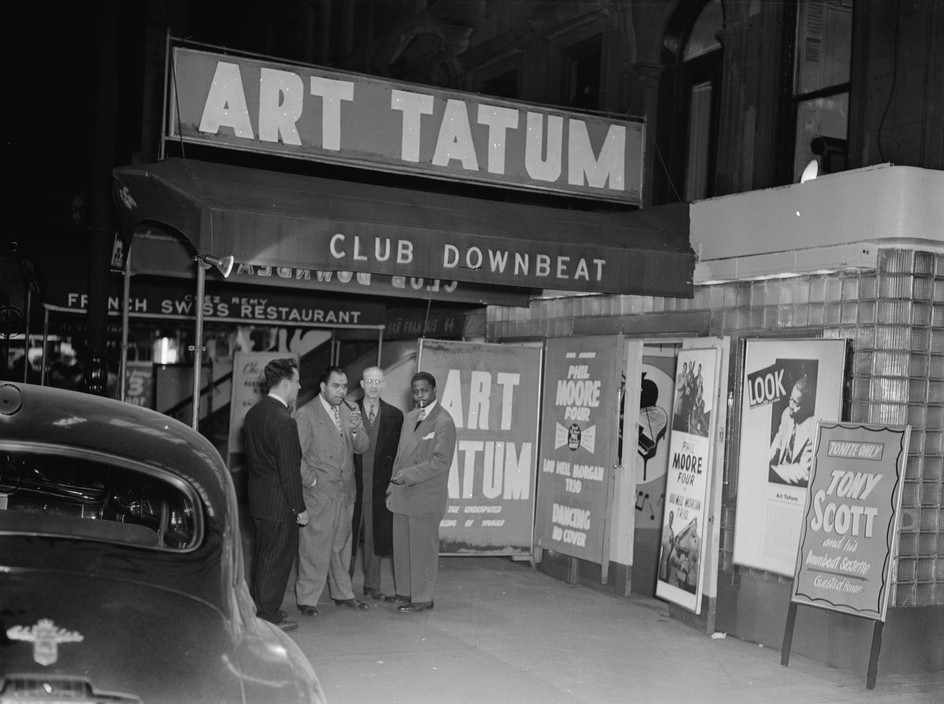

Art Tatum and Phil Moore outside New York jazz club Downbeat, between 1946 and 1948 (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

In 1943, the cabaret law’s reach was extended, with a requirement that all New York City musicians carry a “cabaret card” to perform at bars and clubs. Musicians had to go to the police department’s licensing division to be fingerprinted, photographed, and subjected to interrogations about their personal life—mostly focused on their potential drug use—before they could be certified as worthy and wholesome. Cards had to be renewed every two years, and the authorities were free to revoke or deny their renewal at will.

Amidst the burgeoning New York jazz scene in the following decades, authorities disproportionately suspended the cabaret cards of black musicians. According to Jazz Times, those who lost their cards included Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Billie Holiday, and J.J. Johnson, many of whom were at the peaks of their careers and, after losing their ability to perform in the city, faced decline or ruin.

“My right to pursue my chosen profession has been taken away, and my wife and three children who are innocent of any wrongdoing are suffering,” Charlie Parker wrote to the State Liquor Authority, after a suspended sentence for heroin possession led to the revocation of his card in 1951. According to Reason, Parker’s card was reinstated in 1953, but he died in 1955—partly from conditions related to stress and self-destructive tendencies built up during his two years without a card.

You started moving a little bit, and the security came and stopped you, and said you cannot dance. It got that ridiculous.—Sophia Lamar

Stand-up comedian Lord Buckley was dragged off stage at a club by plainclothes officers and had his card suspended in 1960 because he had neglected to inform the police of two minor arrests during his cabaret card application. Lord Buckley died of a stroke only a few weeks later.

In response, writer Harold L. Humes convened a “Citizens’ Emergency Committee” of well-known members of the New York intelligentsia, bringing attention to what he described as “the exquisite Chinese torture that passes for the standard operating procedure of the Police Cabaret Bureau.”

Buckley’s death only added fuel to the scandal’s fire, and in 1961, Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr. made the conciliatory step of taking the cabaret cards out of the New York City Police Department’s control. Nevertheless, it took the involvement of Frank Sinatra to finally get rid of the card system entirely. Sinatra had publicly described the application and investigation process as “demeaning,” and refused to play in New York during the prime of his career. Finally, at a City Council meeting in 1967 that included a reading of a message from Sinatra, the card system was finally abolished, ending a nearly decade-long struggle by musicians and other cultural figures.

The Lessons ‘Footloose’ Can Teach Us About Political Resistance

The cabaret law was amended again in 1986 and 1988 to remove the “three-musicians” rule and restrictions on jazz instruments. But its mark had already been left on jazz culture. “The places in which jazz musicians can play can probably be counted on two hands,” wrote the same New York Times article from 1987. “So, the vestigal cabaret law continues to jeopardize the growth and maturation of America’s most imaginative and important contribution to world music.”

In the 70s and 80s, according to the Huffington Post, the cabaret law’s regulation on dancing was loosely enforced. But in the late 90s, Mayor Rudy Giuliani revived the law to inflict fines and closures on unlicensed bars and clubs as part of his “quality of life” campaign, which “demonized nightlife as our city’s bastard child, trying to smooth it over in order to make things safe for tourists and co-op owners,” as Michael Musto put it in an essay for THUMP. Under Giuliani, task forces of police officers were assembled to go from club to club looking for cabaret law infringements and conducting raids.

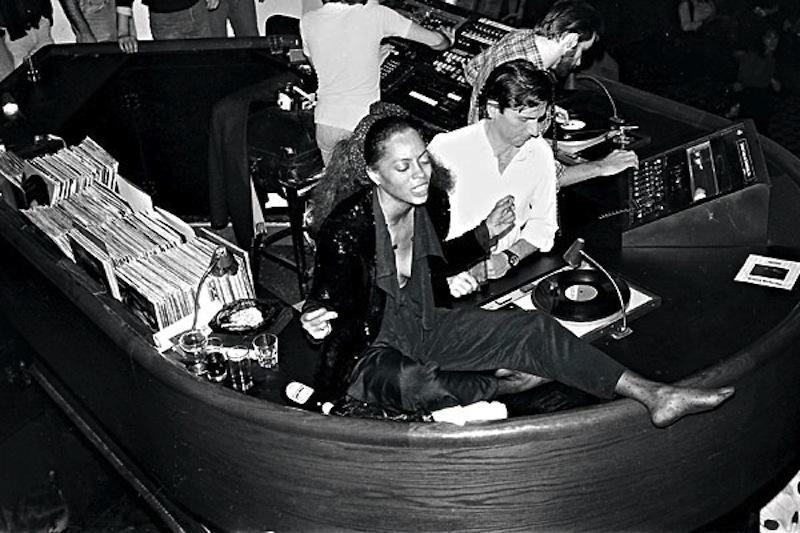

Studio 54, (1977-1981) (Photo via The Strut)

Naturally, Giuliani’s 1990s redeployment of the law was also fraught with race- and class-based discrimination—it was, and continues to be, particularly damaging for smaller Latin clubs above 59th Street. Sophia Lamar, a New York promoter who ran with the club kids, remembers how Giuliani used the law to constrict the anything-goes nightlife of the East Village in the 90s. In a practice that persists today, many bars and clubs featured signs that warned, “No Dancing Allowed.” “It was very funny,” she said in a phone interview. “You started moving a little bit, and the security came and stopped you, and said you cannot dance. It got that ridiculous.”

Steve Lewis started as a club operator in the thick of the “DJ revolution” of the 80s and 90s, with house and hip-hop music on the rise in New York City. It was the golden age for mega-clubs like Mudd Club and Danceteria. Sex and drugs were rampant, as was AIDS. Lewis remembers it as a terrifying, tragic, but also thrilling time. “Wrecked cars, garbage cans with fires in them, people lurking in corners—there was danger lurking everywhere,” he says. “You would open an unmarked door. There would be 300 people dancing at 6 AM.”

If this era of New York nightlife was the “DJ Revolution,” then the cabaret law was Giuliani’s preferred weapon for his counter-revolution, which also included a crackdown on drug use and underage drinking. The East Village, Lewis says, “was particularly picked on because of the development of the real estate.” So were places that “had attracted a hip-hop crowd or urban crowds.”

Enforcement of the law continued under the Bloomberg administration, which led venue owners to devise inventive workarounds: at Brooklyn’s Plant Bar in the early 2000s, if the bouncer suspected police inspectors were approaching, a flip of a switch would notify the DJ to cut the dance music and instead play Radiohead’s introverted, thoroughly undanceable “Kid A.” But the club was cited anyway when a DJ ignorant of the notification system kept the beat going, and has since closed down.In 2008, the Bloomberg administration seemed to have a change of heart, and reports indicated that City Hall was looking to repeal the cabaret law altogether, with Gretchen Dykstra, then the commissioner of the city’s Department of Consumer Affairs, telling the New York Times that she wanted to put “the dance police” out of business. But nothing came of the effort, and, with minimal fanfare, the repeal seems to have been largely forgotten by both the city and the public.

NYC Dance Parade in 2016 (Photo via Flickr/Steven Pisano)

Since then, Mayor De Blasio has relaxed enforcement of the law—but it remains on the books.

Greg Miller, who is in charge of a nonprofit called Dance Parade that aims to promote dance as an art form, says the law ends up restricting those who don’t have the financial resources to secure the proper permit. “If you’re a small business guy wanting to create a cool bar/restaurant that has dancing, then you definitely come up against the cabaret license requirement,” he says. Dance Parade recently hosted an event at the Taj Lounge, which ironically had a “No Dancing” sign above the reception.

Contemporary attitudes on the cabaret law are conflicted. On one hand, Lewis defends Giuliani’s revival of the law on the basis that there is “selective enforcement” by cops against troublesome nightlife spots. On the other hand, Miller opposes the law on the grounds it is “over the top,” with zoning, alcohol licenses, and other laws already regulating nightlife in the city.

Regardless of whether or not the cabaret law has brought peace and order to New York City, the fact remains that it has been—and still is—an instrument which the police can use against any unlicensed establishment where people dance. And, more often than not, targets have been marginalized people. For that very reason, there is also no doubt that people will continue to fight this archaic tool for oppression. As New York anarchist Emma Goldman put it, when a man told her that it was undignified for a political agitator to boogie down, “If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be part of your revolution.”

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Ubisoft -

Isabel Pavia/Getty Images