In our Dancing vs. The State series, THUMP explores nightlife’s complicated relationship to law enforcement, past and present.

At one point in the 1990s, I nearly plotzed with shock as I was carded at the door of a bar. This hadn’t happened for quite a while; most night spots didn’t card at all, and besides, I was rapidly approaching middle age. But it was the Giuliani era, and some venue owners were starting to realize how strict they were going to have be to stay in business. No chances could be taken when it came to the law, even if my ID was practically an AARP card!

Videos by VICE

I’m all for making New York City nightlife safer and more livable. But I’m not in favor of sucking all the life of it, so it becomes a terrified place full of people minding their Ps and Qs while looking behind them to see if they’re going to get busted for having fun.

As mayor of NYC from 1994 through 2001, Rudy Giuliani demonized nightlife as our city’s bastard child, trying to smooth it over in order to make things safe for tourists and co-op owners. Ignoring the fact that nightlife pumped money and creative excitement into the city (which many tourists and co-op owners would have loved), he steamrolled over the industry, at the same time taking the porn out of Times Square and making it ready for people in Mickey Mouse costumes.

Watch author Michael Musto explain how Giuliani destroyed New York’s club scene in the 90s—and what club kids did to fight back.

Squashing nightlife was part of the mayor’s broader initiative to reduce crime and improve the city’s so-called “quality of life.” To that end, he used both new and existing regulations to monitor nightclubs, including taking the cabaret law—a bit of archaic legislation that decreed there couldn’t be more than three people dancing in a boite without a cabaret license—out of mothballs and using it to punish places full of happy feet.

Penny Arcade, the longtime performance artist whose 2002 show New York Values railed against Giuliani for robbing NYC of its identity, remembers how the authorities targeted venues that didn’t have cabaret licenses. “One Avenue A bar that was a cafe during the day and a gay bar at night was fined thousands of dollars for people swaying to the music!” she told me. “And if the cops returned after they fined them and found someone dancing, the bar was fined $1,000 per night for every night since the original violation. Who wanted to go to nightclubs with police raids?”

Arcade still fumes at the mayor’s impact on nightlife. She recalls Giuliani-ordered quality of life club raids, conducted by police officers who formed what she calls “task forces of morality agents.” These task forces went around from club to club looking for infringements. “They handed out violations for dancing, smoking pot, exit lights—whatever they could find, financially crippling the club owners,” Arcade explained.

Around the same time, local community boards across the city were becoming more powerful and denying licenses to wannabe hotspots. The hoity toity board members didn’t want noise or “bad people” in their neighborhoods. Welcome to the new New York. Party!

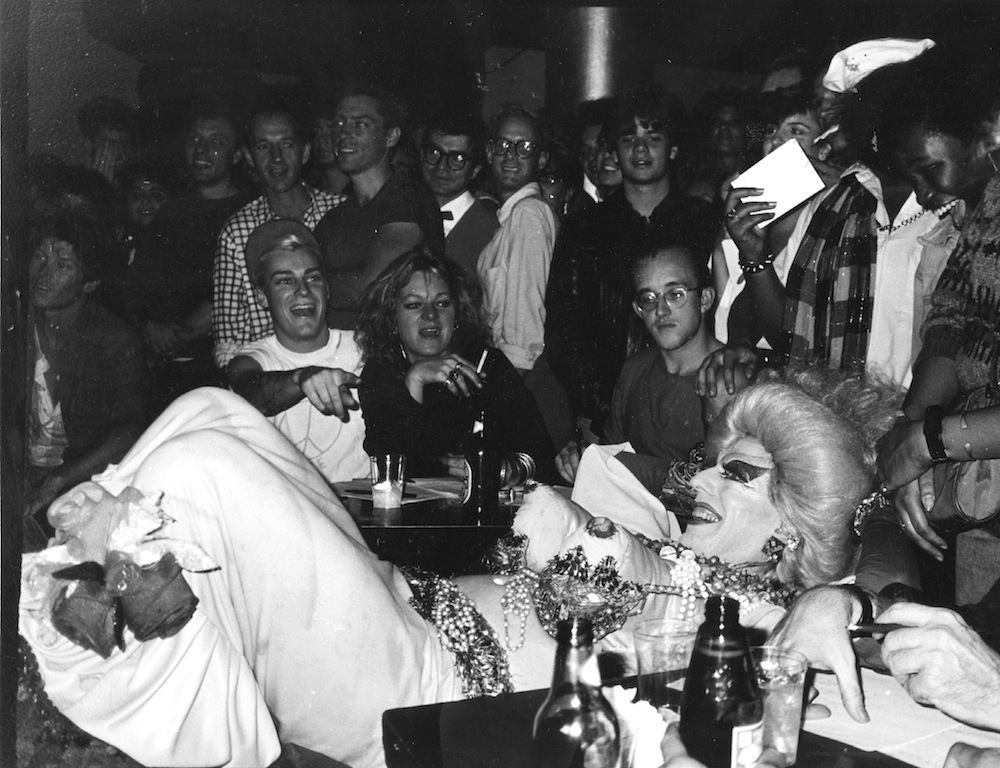

Ethyl Eichelberger, Keith Haring, John Sex, and Cookie Mueller at Danceteria in1984. (Photo by Joseph Modica)

True, the city’s violent crime rate did go down by 56 percent during Rudy’s two terms, according to the FBI Crime Index, and we no longer lived in as much fear of constant muggings. But at what price? Giuliani clearly wanted to take the fun out of what was once known as “Fun City.” When he arrived in the mid-90s, the 80s scene of booming dance clubs was already on the decline. The arty Tribeca dance club Area ended in 1987, by which point it had run out of steam (Quick!, the club that replaced it, was nowhere near as enticing). Raunchy gay disco the Saint closed in 1988, its clientele ravaged by AIDS, and the third location of rock/dance club Danceteria shuttered in 1993.

On the ascent were lounges—virtually dance-free venues where you sat and got rigor mortis as you tried to scream over Top 40 songs, hip-hop, and dance-pop. This partly came about due to Rudy’s obsessive scrutiny of clubs, as he frantically searched for reasons to fine them or shut them down. Lounges like Spy Bar, which opened in SoHo in 1995, kept popping up as a counter-balance to the crazy club kid scene, which by that year had already started showing signs of losing energy, as Michael Alig got messier and more desperate for attention. There was occasionally some awkward dancing between tables at Spy Bar, but it was nervously done, the customers aware that they were engaging in something wildly taboo. I started likening NYC to the town in Footloose, where dancing was illegal!

Who wanted to go to nightclubs with police raids?—Penny Arcade, longtime NYC performance artist

Through much of the mid-90s, I would get calls from thuggish-sounding people I suspected were either Feds or on Giuliani’s team, trying to get dish on any illegal activity allegedly committed by Peter Gatien. Gatien—a favorite target of Giuliani—was owner of the racy church-turned-nightclub the Limelight, which hosted many of Michael Alig’s club kid parties. Gatien was cleared of charges that he was involved in drug sales at his club in 1996, but he did eventually get busted on tax evasion in 1999, and was later deported back to Canada. It was almost as if authorities were trying to catch him on any charge they could find.

The Comeback Kid: Michael Alig’s Return to New York Nightlife

But it was in 1996 that Giuliani got his “Told you so” moment. That year, the tragic killing of clubbie Angel Melendez by Michael Alig and his roommate Robert Riggs helped fuel the fire beneath the mayor’s campaign. The grisly killing and dismembering of Melendez gave credence to Giuliani’s agenda of pushing the idea that terrible things can happen because of nightclubs, and that therefore, we needed way tighter strictures on nocturnal behavior. While I agree that Alig had too few boundaries surrounding what he could get away with, bad things happen on the police force too—does that mean you eradicate the entire squad?

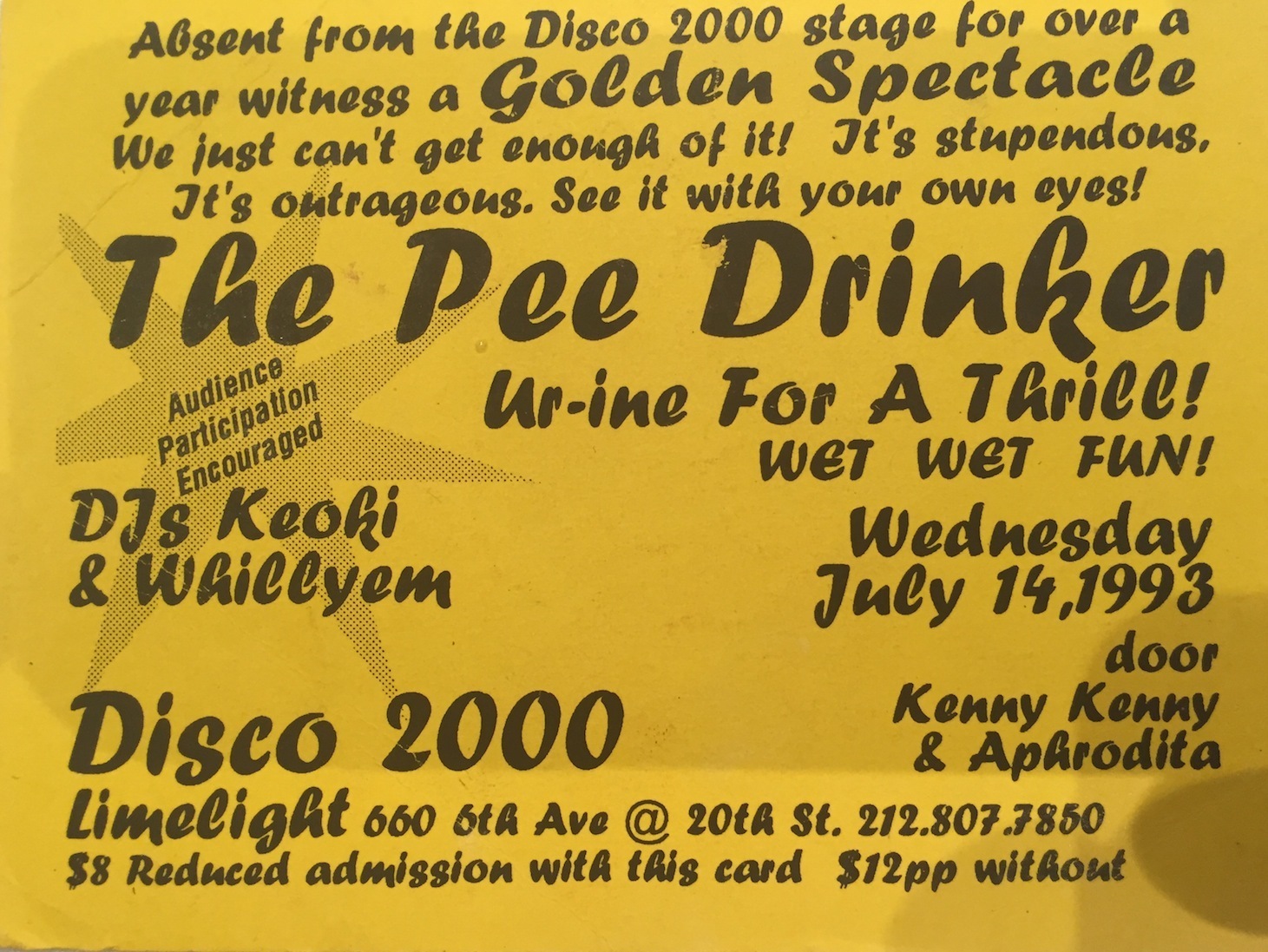

An invitation to a Disco 2000 party at Limelight in April 1993 (Photo courtesy of Michael Alig)

And things got worse. After the killing, there was a sense of doom in the air as many club people started chilling out and self-policing. A wave of conservatism kept creeping in from within the scene itself. Even those who hated Giuliani began realizing that it was no longer cool to be a club kid, so many of them quickly retired their lunch boxes and rethought their personas. In their place, the credit-carded gang dominated the new lounges, and were springing for bottle service—wildly overpriced bottles of vodka and trimmings, served by busty blonds. Spy Bar is credited with—I mean blamed for—having initiated this trend, which certainly hauled in tons of cash to clubs that dared to go there.

The shift in emphasis from large, riotous nightclubs to staid, sit-down lounges felt traumatic and a little too permanent. In the late 90s, the Meatpacking District started burgeoning as boutiques, restaurants, and wan hangouts like Tenjune and PM Lounge emerged in an area that was previously home mostly to slaughterhouses, packing plants, prostitutes, and a bagel shop (and before that, gay sex clubs). The neighborhood became the backdrop for the kind of yuppie lifestyle reflected on Sex and the City. Even the long running 24-hour French restaurant Florent started attracting a more conservative looking crowd than before. And just a few blocks away was Moomba, a sceney restaurant/lounge in the West Village where, starting in 1997, celebs would come to schmooze, pose, and imbibe.

Get to Know Suzanne Bartsch, the Snazziest Dresser in New York Club History

If anyone hadn’t heard the death knell for creative nightlife yet, the ascent of bottle service rang it loud and clear. Eighties clubs like Area had been focused on art, performance, and dance, but now, sitting down and paying way too much for a drink was considered the height of expression. At the same time, technology was changing the way people connected and throwing a wrench into the fun of going out. With the rising popularity of HBO in the late 90s, it was suddenly considered acceptable to say you were staying home to watch TV instead of going out. The internet was also coming around as a means of communication, and people I knew who had gone to clubs all the time were starting to find themselves on the computer all night.

But nightlife, which is generally tailor-made for outcasts and oddities, has a way of fighting back against oppression. In revolt, I kept dressing up even wilder and continued going to the fetishy club Jackie 60—a beacon of bohemia in the changing Meatpacking District—through the end of the decade. Party promoter Susanne Bartsch also kept beating her drum, attracting a conga line of wonderful wackos who defied everything that was going on under Giuliani’s dicta.

Susanne Bartsch in New York City (Photo via “Fashion Underground: The World of Susanne Bartsch”)

Other flamboyant corners of the club scene flourished, such as drag, thanks in part to RuPaul and movies like The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert. Early in Giuliani’s run, I rouged myself up, donned heels, and appeared in a 1994 video Cyndi Lauper directed for her remake of “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun.” Drag kept evolving after that, and the queens got even zanier and performed in campy Jackie 60 stage pageants, indulging in colorfully outrageous antics as if Giuliani had never happened. In 1998, I co-wrote “Daddy’s Little Prostitute: The JonBenet Ramsey Story,” a sardonic but pointed romp with scenesters Flloyyd, Sweetie, and David Ilku in the leading roles. Those who survived it are still scandalized.

Nightlife people were more connected than ever because we were the only ones left carrying on like that. In this new era of tightening regulations, being outrageous took on a different air. We felt extra edgy—a feeling that had started to drain out of the culture, thanks to Giuliani’s creepy colander. In the mid 90s, SqueezeBox!—a weekly party at Don Hill’s—erupted as a haven for drag queens, rockers, and poseurs, the only rule being that lipsynching was not allowed. The diverse crowd was distinctly against Giuliani’s relentless whitewashing of the city, and the result recaptured rock’s rebellious spirit, until the party ended in 2001.

Today’s nightlife still faces all kinds of challenges, like stringent security checks that make you feel like you’re getting on an international flight, plus steep prices and the fact that people generally hook up via apps and sites, not at clubs. The long-running weekly gay party Beige went kaput in 2011 when a condo rose up next to it and filed noise complaints. But the party scene carries on, a compromise between the flamboyance of the 80s scene and the repression that chilled the 90s one. There’s a new batch of club kids, but because of rising costs of living in the city, a lot of them go home to their apartments in Brooklyn—the borough where a lot of the clubbing has moved, for financial and zoning reasons—at a reasonable hour, so they can wake up and earn a paycheck the next day.

Still, without Giuliani—or his successor, Michael Bloomberg, who was also strict—there’s a slightly more playful ambience today. It’s not all peaches and cream, though. Just last year, I was booted off a banquette at the club Stage 48 because it was reserved in case someone came in and wanted to order bottle service!

Giuliani’s impact on nightlife is still strongly felt every time you see a roped off bottle service table, are patted down and told to be quiet outside a bar, or have to pay for a $15 Uber to get to a far-flung dance club. “Fundamentally,” says Penny Arcade to me. “Giuliani set out to deliver the broken spirit of NYC to America, which resented the freedoms, sexual and otherwise, that NYC had long symbolized.” It’s comforting to know that this spirit will never truly die, whereas Giuliani’s political career seems to have done exactly that.