The Los Alamos cafeteria, via the LANL site

We think of the nuclear age as being fathered by giants. But for all of the famous and infamous names credited for developing the most destructive technologies in human history—Dr. Edward Teller, the severe pragmatist who wanted to use nukes in place of shovels; Robert Oppenheimer, who was left shell-shocked by Pandora’s box; and of course Einstein—there were hundreds more people working behind the scenes, keeping the Los Alamos National Laboratory running.

Naturally, because Los Alamos during the Manhattan Project (then known as Project Y) was a tightly secure government facility, all of those faces were photographed for ID badges. Those badges, which have since been digitized, stated where staffers could go, and perhaps more strangely, who they could talk to.

Videos by VICE

Thanks to some awesome work by Alex Wellerstein at the Nuclear Secrecy blog (and later added to for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists), we can now see a cross section of all the people who helped make the bomb.

Robert Oppenheimer was just one of the engineers working on splitting the atom, and has split credit for being the “father” of the bomb with Enrico Fermi. But in years since, he has become the face of atomic bomb regret, whether deserved or not. Largely, that’s due to his infamous interview in which he quotes Hindu scripture, saying “I am become death, destroyer of worlds.” Contrast that moment with his much younger face above, and you can see the weight of the bomb on his person.

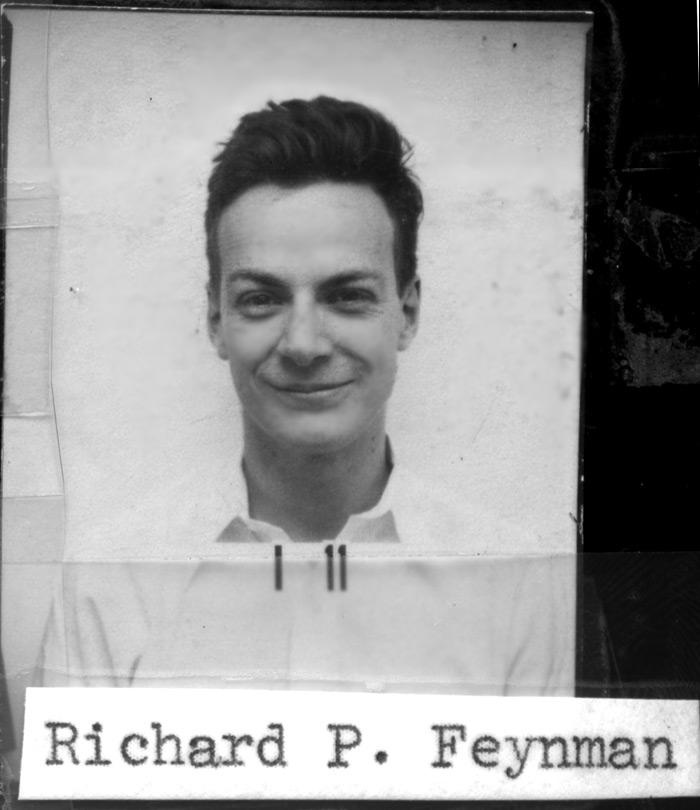

Contrast Oppenheimer, the consummate stone-faced engineer, with Richard Feynman, a physicist described by the Bulletin as a “mischievous young genius.” Feynman, whose smirk may be attributable to his apparent disdain for the security measures at Los Alamos. (Seems rather quaint today, right?)

Smiles aside, Feynman was no slouch, and went on to win the Nobel Prize in physics in 1965 with Sin-Itiro Tomonaga and Julian Schwinger for their work in quantum electrodynamics.

Not all of Los Alamos’s scientists were male, although physicist Elizabeth Graves did join the lab with her husband Al, also a physicist. Los Alamos was truly a family affair for the Graves, as Elizabeth, who was a top expert in neutron particle scattering, continued lab work while pregnant.

As part of their duties, the couple was sent to monitor radiation levels during the 1945 Trinity test, which was the first ever detonation of a nuclear device. Because Elizabeth was pregnant at the time, they requested to be sent far away from research posts near Ground Zero. They ended up at a motel 35 miles away, which was well within the theoretical exposure region for the radioactive cloud. It’s unclear how much exposure they faced, but the baby ended up fine.

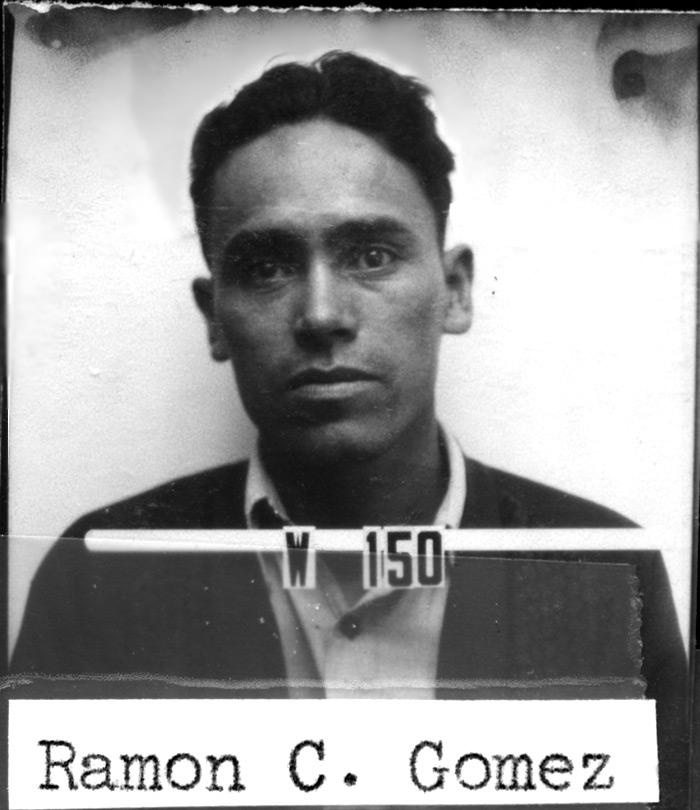

Credit to the Bulletin for including Ramon Gomez, one of many native New Mexicans working at Los Alamos. For all their fame and importance, the Los Alamos labs were a small part of the Manhattan Project, employing just a few thousand of the more than 120,000 people employed by the project. And of Los Alamos, there were plenty of support personnel whose names have never been widely shared.

Gomez’s granddaughter Myrriah Gómez commented on the Nuclear Secrecy blog to say that Gomez and his four brothers worked to clean and decontaminate lab equipment at Los Alamos, a rather thankless and dangerous job, and all five eventually succumbed to cancer. She spoke with Wellerstein for his Bulletin post, and said that her family’s experience is just one piece of the dark legacy left by Los Alamos for New Mexico locals.

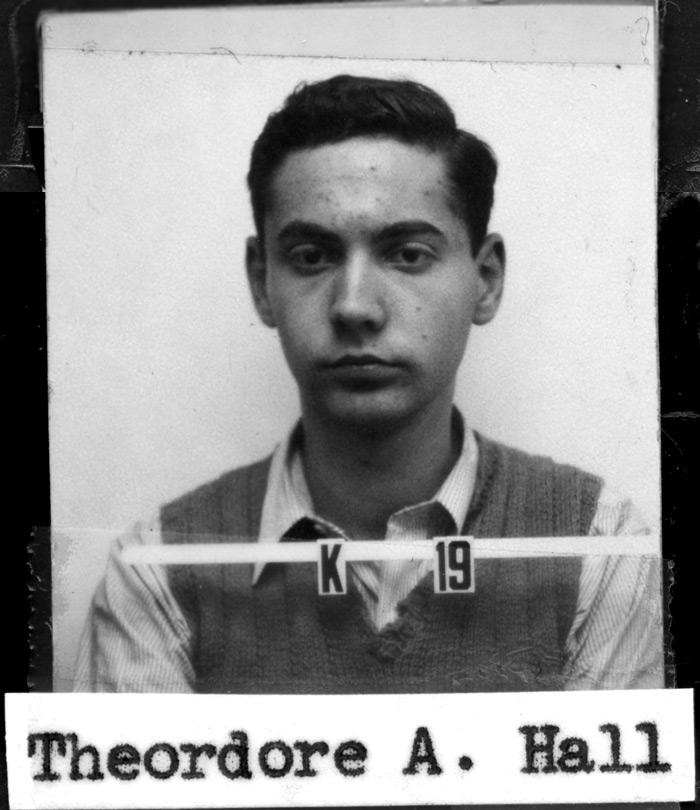

In light of the US government’s obsession with finding and prosecuting Edward Snowden, it seems fitting to close out our roundup with the tale of Theodore Hall, Hall, a 19-year-old Harvard undergrad, was the youngest physicist on the Los Alamos team, and something of a smartass.

There’s no denying that he was gifted, but for whatever reason, Hall became disillusioned with the project. Eventually, he allegedly met with representatives from the Soviet Union, and became a Soviet spy, giving up both knowledge of the Manhattan Project and technical details. As his New York Times obituary notes, he give an opaque admission, saying that he felt such power shouldn’t be held in the hands of just one nation.

In other words, while Hall wasn’t the only Soviet mole within the Manhattan Project, he did have a hand in hurtling the world towards the specter of mutually assured destruction that still haunts us today. He was never convicted.