All photos by the author

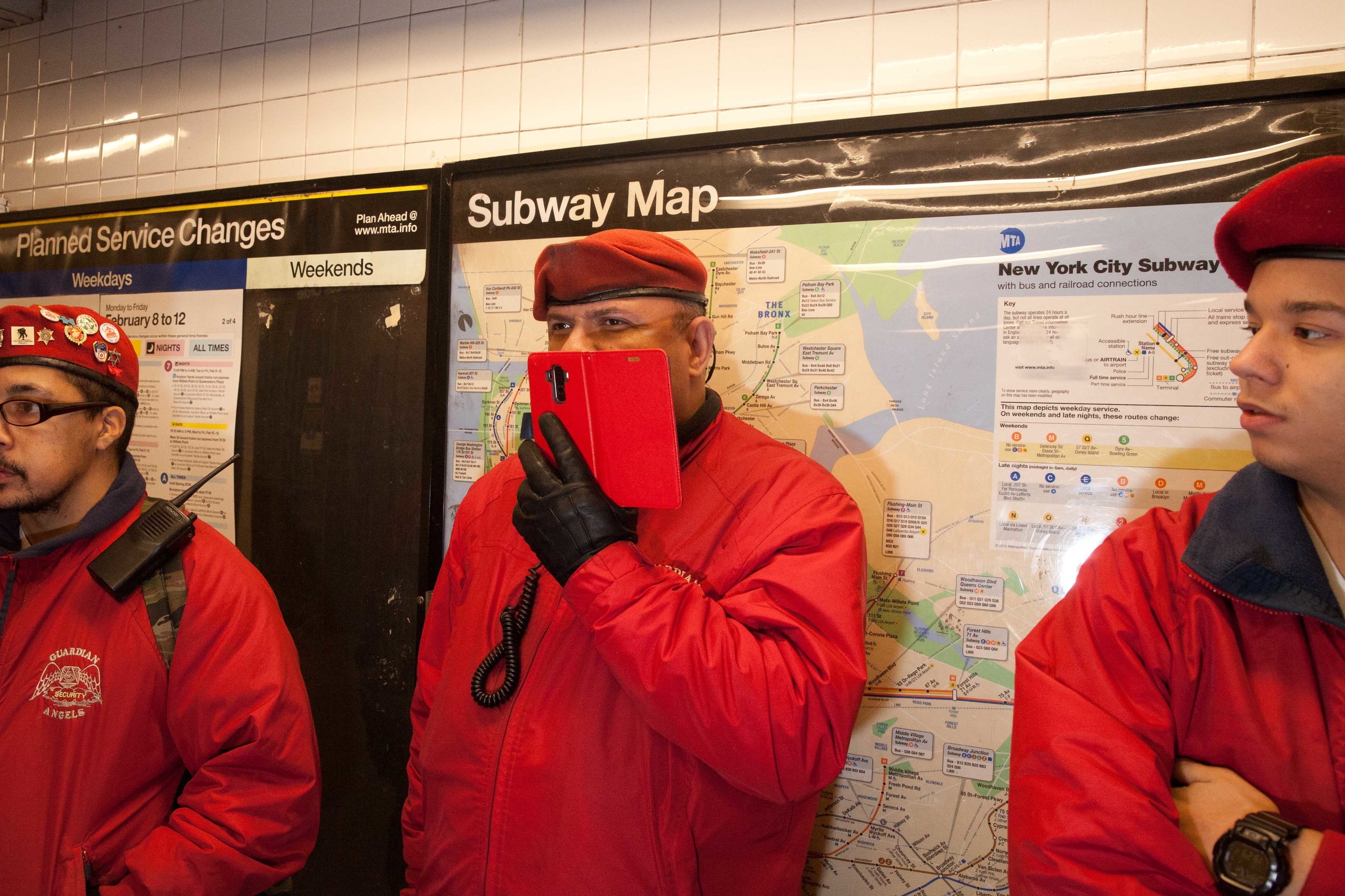

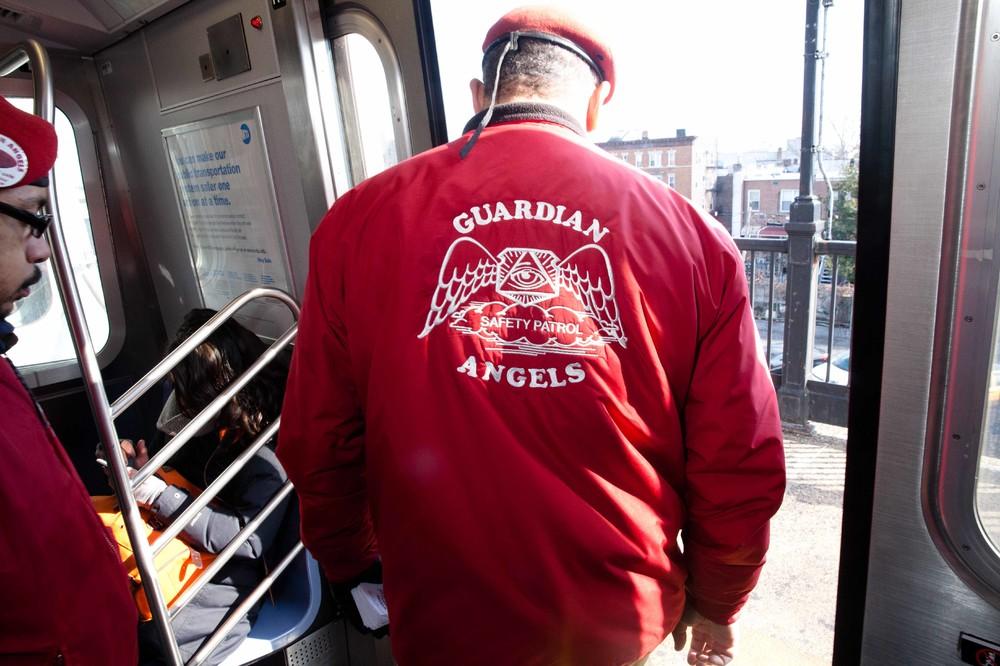

New York City is full of characters walking around in costumes—the topless women of Times Square who perform for money, the bankers roaming Wall Street in their double-breasted blazers, the cops and ravers and Bloods and aspiring fashionistas. But of all the city’s outfits, the red jackets and berets of the Guardian Angels are branded deepest in my brain.

Founded in 1979, the Guardian Angels were supposed to be a counter to the muggings and assaults that back then were commonplace on the streets and subways. The local authorities, as you might imagine, weren’t too keen on private citizens fighting crime, but in 1981 the city and the Angels reached a “memorandum of understanding” where the vigilantes agreed to work with the cops.

Videos by VICE

How much crime the Angels prevented is unclear. In 1992, founder Curtis Sliwa admitted to faking a half-dozen acts of heroism to gain publicity in the group’s early years; by that time, his former associates had accused the Angels of becoming, according to the New York Times, “little more than a security force for a block of midtown restaurants.” Sliwa is also known for his sexist and racist remarks, which hasn’t exactly improved the group’s image.

Still, the legend and iconography of the Guardian Angels persists. I first became aware of the volunteer-based group through a photograph I saw when I was 12. In the 1980s, photographer Bruce Davidson documented the NYC subway system in all its gritty glory. In one of his most striking images, two young men in white tank-tops emblazoned with “Guardian Angels” stare stone-faced in front of subway doors. The photo is unequivocally of another time: The mustache on one Angel, the glasses, the sleeveless muscle shirt, the neat afro, and the graffiti that lined every exposed inch of the subway.

Today the subways are cleaner and the city is more orderly; romanticized though it is, no one wants to return to the grimy, gritty days of the 70s. Nevertheless, earlier in the month, local news outlets reported that the Guardian Angels are “back on patrol” on the city’s trains. But to hear 32-year Guardian Angel veteran EQ (a.k.a. Benjamin Garcia) told me, “We never left”—New Yorkers just haven’t been paying attention.

One reason for the Angels’ resurgence is that despite statistics demonstrating New York’s safety, tabloid accounts of subway knife attacks, among other things, have some residents spooked. (That Mayor Bill de Blasio, a Democrat, has supposedly been insufficiently pro-cop has made some conservative New Yorkers skittish about a return to the “bad old days.”)

To learn more about the Angels and what purpose they serve in 2016, I spent a full day with them as they patrolled the subways.

During the morning patrol, I met EQ, Tito Colon (appropriately nicknamed “Mumbles”), and a third, seemingly mute, member named Chavi at 11 AM outside Columbus Circle. After we went underground, the members did a pat down of each other near the Metrocard machines to make sure no one was carrying weapons, intentionally or unintentionally, while on patrol. Once through the turnstile, they alerted an officer behind a desk in the police department at the 59th Street station that they were going on duty. The police officer, looking baffled, replied “OK,” and gave an awkward wave.

With only three members on duty, the Angels roamed the same subway car together and changed cars at every stop. “The most dangerous train is the A to Far Rockaway,” EQ explained to me authoritatively. “All the muggings happen there.” He also lists the Brooklyn-bound L, J, 3, and 2 trains, as well as the Flushing-bound 7 train, as the other dangerous lines they frequent.

EQ told me that the Guardian Angels are taught self-defense and regularly practice role-playing scenarios, and some of the members know mixed martial arts. EQ couldn’t clearly answer when I asked him what the procedure was if they found something or someone who was suspicious. In all the different responses he gave me, he never mentioned notifying the police.

Chavi, who remained silent for the entire six-hour morning shift, often picked up garbage on the subway platforms, sometimes using tools from his utility belt to assist in the pickup. EQ acted primarily as the group’s promoter. Whenever someone so much as glanced over at the men in costume, he quickly gave them a handshake with one hand and magically procured a business card for the Angels with the other. When a train car was empty, all three would place little fliers in between the plastic cover for advertisements. EQ told me, “With these cards and fliers, we get about five recruits a day.”

After riding the 7 train to 103 St-Corona Plaza, we stopped in a McDonald’s so that EQ could follow-up with some of the recruits over the phone. Most of the conversations ended with, “Sorry, thanks for your time.”

EQ estimated that they stop an actual fight once every three months, often involving gangs or bullies picking on high school kids. The Angels take it upon themselves not only to fight immediate physical violence they witness, but also to return lost children to their parents or protect women who are being harassed by men.

“Ten or 12 years ago, there was a 15-year-old girl in Queensboro Plaza,” EQ told me. “She had this stalker. We switched cars and the stalker got on with us. Looking at me, he said, ‘There’s nothing you can do and I’m gonna get away with it.” EQ said that he tackled the guy while doors were open in a station and pinned him down until the cops arrived.

A few hours later, I joined several more Angels for a night patrol. There were three new members: 22-year-old Crazy J (a.k.a. Jose Gonzalez), 16-year-old Blue Blood (a.k.a. Ivan Cruz), and Rock (founder Curtis Sliwa), as well as EQ and Mumbles working a second shift. On the A train downtown, Crazy J told me how he believed that the recent subway slashings were an anomaly and that the city is much safer now than it was when he first became an Angel.

The vibe on the evening shift was more intense than the day shift, and the volunteers acted as if there was more gravity to what they were doing, perhaps because their leader was overseeing them. Upon entering the train cars, all eyes were on the Angels with their crossed arms and red berets. There were two types of reactions: Those who simply stared and appeared baffled by the men in red outfits, and those who approached the Angels and shook their hands. Many people who approached them were shocked that they were still around. On multiple occasions, middle-aged men stopped the men to thank them for their service and to retell stories of how safe they felt seeing the Guardian Angels patrol the trains when they were kids.

“It’s good to have you guys back,” one commuter told them. “We need you.” After the man exited the train, several of the Angels seemed to follow the fan with their eyes until the train left the platform and headed south to Canarsie.

Visit Jackson’s website and Instagram for more of his photo work. See more photos of the Guardian Angels below.