I drift in the space between the twin worlds, Ash and Ember, counting the minutes and watching as sand falls. The two planets, locked in a combative binary orbit, are a celestial hourglass: The seemingly endless desert of Ash is sieved away by gravity, spread over the cracked red crust and deep crevices of Ember.

Maybe if I was further away, it would be a beautiful, toothless vista. Just a sci-fi postcard from this often cartoonish world. But from this close, implausibility is overcome by raw scale. The sun is lost behind the column of falling sand, and the rumble of this planetary runoff makes the threat clear: If I pulled too close, my ship and I would be crushed under the weight. A million million little grains of dust would shatter the glass of my cockpit; ruin my landing gear; send my reactor critical.

Videos by VICE

But from this distance, I’m safe for now. I need Ash to empty so that I can crawl into a door that is currently buried in its desert. That will take about 15 more minutes. Which is good, because the world won’t end for another 20.

This is Outer Wilds, a first-person game of exploration and ecology developed by Mobius Digital and published by Annapurna Interactive, and releasing tomorrow on Mac, PC, and Xbox One (where it’s included as part of Game Pass). And as I’ve tried to explain it to friends and co-workers over the last week, I’ve realized what a difficult thing to pitch it is. So let me start with this, plain and easy: Outer Wilds has stolen every night (and a couple of days) from me for the last week, and I’m thrilled that it has. I don’t know that I’ve ever played anything like it, and I don’t know when I’ll get to again.

If you forced me to explain the game in a single paragraph, it would go like this: Outer Wilds is a first-person exploration game that casts you as a fledgling astronaut and archeologist. You travel between six worlds (and a handful of other astronomical objects) in order to piece together the history of a missing culture, stop the destruction of the solar system, and solve the mystery of a Groundhog Day-esque timeloop you’re stuck in. While there’s the occasional jumping puzzle, it’s mostly a game about walking around and flying between beautiful planets. There’s no combat (though there are hazards to scout with a camera probe you can launch around corners and into dark caves), and there is limited dialog with NPCs, though what there is is well used. In an elevator ride, maybe you’d say that Outer Wilds is Majora’s Mask’s time-loop meets the epistolary storytelling of Gone Home meets the golden age sci-fi cover aesthetics of No Man’s Sky.

But this is so reductive, sanding off all of Outer Wilds most unique edges in order to sell something frighteningly fresh in the comfortable uniform of the familiar.

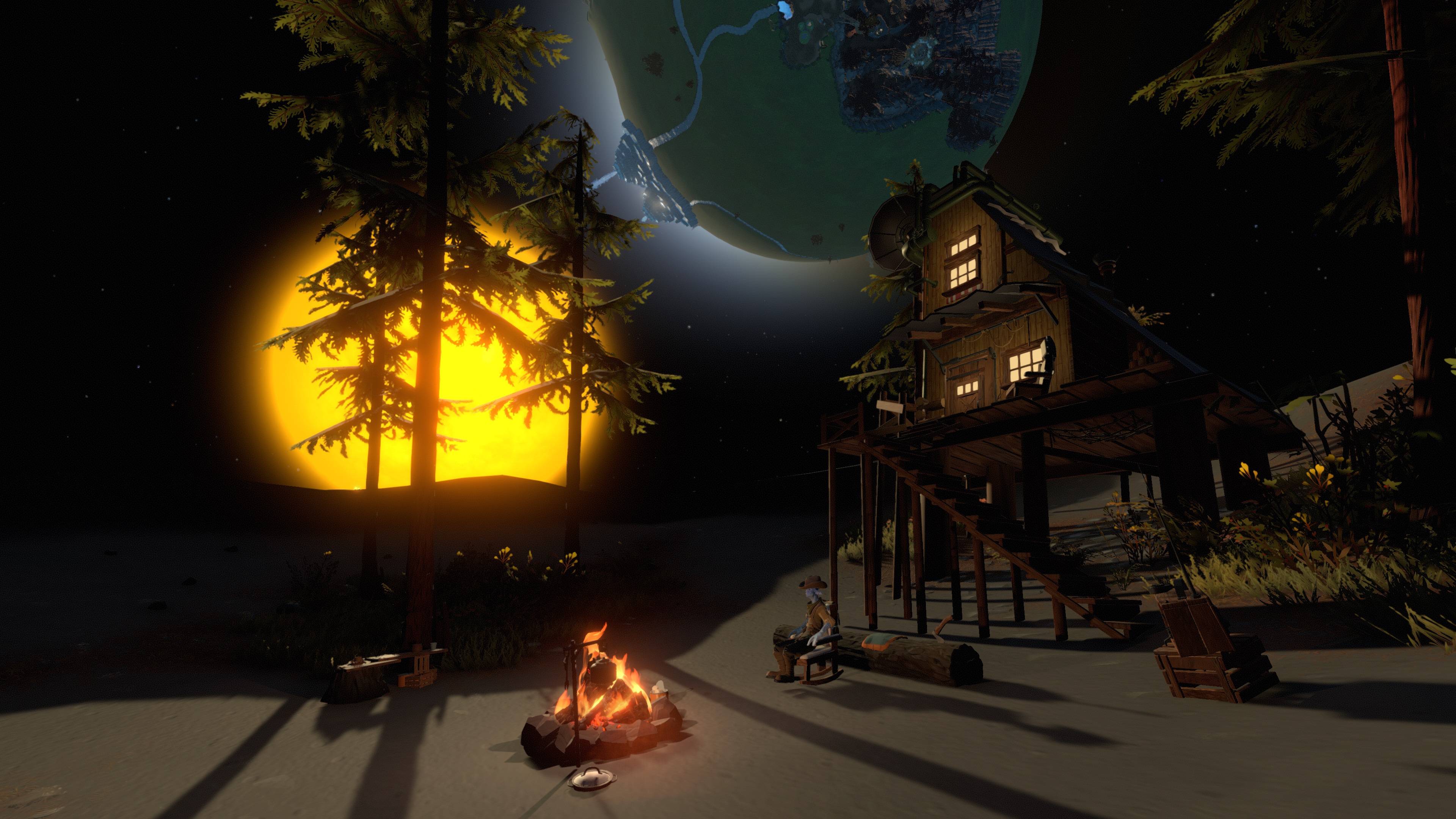

First and foremost, that description fails to capture the game’s open-ended structure. After learning how to use your jetpack and your camera probe on your arboreal homeworld of Timber Hearth, you’re encouraged to travel to your planet’s moon. There, you can test out a new device that can translate the alien writing that marks the system’s many ancient ruins. After a quick hop in your ship and a few scans with your translator, and a threaded map of “rumors” is added to your ship’s computer, and you’ll spend the bulk of the game choosing which of these threads to pull on.

It’s hard to oversell how key this interactive journal of information is to Outer Wilds. When you read a message in an escape pod that refers to a science station on a nearby world, the map updates, drawing a line from the escape pod entry to the one for the (potentially newly added) science station. As you bounce from one planet to another, this map of locations, characters, and events grows larger and more connected, but never becomes too complicated to navigate or refer to for a quick refresher. You can click deeper into each entry to see a list of all of the important information learned at each place, and the menu even notes if you’ve missed key information anywhere you’ve already been.

I know it might be hard to get excited for what I’m basically describing as a good video game menu, but the reason this matters so much is because of how it enables a particular mode of self-guided exploration. Without it, the dense planets and many mysteries of Outer Wilds would be simply too hard to keep a grasp on. It would also be too easy to forget the solutions for the game’s many organic, environmental puzzles that are the heart of the game’s main “loop” of play.

Each of Outer Wilds’ planets has unique ecological features that dramatically changes (and challenges) how you explore them. You’ll face differences in gravity, weather, structural stability, wildlife, and other elemental hazards as you climb through the rubble of alien cities or tinker with their super-science devices. Over and over, you’ll encounter some new obstacle and then—whether through careful study of the phenomenon or through a revelation recorded in an exchange between long-dead alien researchers—you’ll learn how to deal with it. This is the most major difference from the oft-compared-to No Man’s Sky: You sit with these handcrafted planets for hours, while NMS offers up a conveyor belt of new, candy-colored worlds to explore.

Outer Wilds has some light “simulation” elements: You need to manage your oxygen and jetpack fuel, and sometimes you’ll have to hop out of your vessel and repair it when it’s slammed too hard into a cliff face or a stray comet. But it’s not a game that leans on abstraction. The violent storms of the oceanic Giant’s Deep don’t simply add a visual layer of rain and lower a temperature gauge. They fill the sea with cyclones that will violently fling you, your ship, and even the island you parked on up into the air. Again and again, I was startled by the way these environmental features directly impacted my play, and stunned only more when I figured out how to mitigate (or at least anticipate) them.

This focus on the environment isn’t only key to exploration, but to the Outer Wilds’ story, too. Though you never see them living their lives, dozens of memorable characters emerge through the messages you find across the system. You’ll learn about the children who played in the city below the dunes; religious mystics who build a faith around quantum mechanics; rival scientists whose respect for each other is surpassed only by the difference in their ethics. As you study the thousands of messages sent between members of the seemingly-extinct Nomai species, you slowly sketch an understanding of a culture desperate to find solutions to environmental crises.

Which leads to the most important way in which that earlier description is reductive: You aren’t only playing as an astronaut or an archeologist. In Outer Wilds, more so than in any other game I’ve ever played, you become an ecologist. And I mean that in the broadest way possible.

In order to successfully navigate the cyclones and waves of Giant’s Deep or the falling sands of the Hourglass Twins, you must internalize the rhythms of those worlds, the rules of their weather systems, and (of course) the repeating loop events. The solar system is massive, environmental network, and each world is a vibrant and wondrous laboratory. There are no upgrade trees or unlockables here. Instead, journeys that once took your full 22 minute cycle become two minute excursions once you’ve learned certain shortcuts and tricks. A hole in the ice that brings you to the (otherwise difficult to reach) city below. A quirk of gravity that lets you use your jetpack to slingshot your way across the planet safely. Knowledge is progress.

But, in line with the ecological label, Outer Wilds also problematizes that concept of “progress.” With each new discovery, the game reminds you that you walk the path of an already-doomed species that struggled with all-too-familiar questions: Can we trust technology solve problems that trust-in-technology caused in the first place? How do we stop those with the power to ruin our ecosystem with unrestrained excess from doing so? Is disaster now inevitable? And, of course, what are we going to do?

In last year’s Being Ecological, philosopher Timothy Morton undercuts the value of that final question—”what are we going to do?”—arguing that we use it as a sort of escape pod, ejecting before we need to confront more difficult questions about what it means to live inside of an ongoing global, environmental disaster. It’s a question that “wants to be relieved of the burden of anxiety and uncertainty,” he writes. “What this type of question is asking, and the way the question is asking it, has to do with needing to control all aspects of the current ecological crisis. And we can’t.” And so we focus on the impossibility of a clean, practical answer instead of spending that energy describing our lives as they are, from the inside of the sixth mass extinction event.

What elevates Outer Wilds is how it confronts this tension between practicality and contemplation. Your exploration rarely feels heroic. In fact, it is often melancholic. There are moments of shout-worthy victory, sure. But as you piece together the history of your little star system, it becomes clear that there are no easy answers.

Every 22 minutes, you hear the telltale musical cue that fires when your loop is coming to an end. You climb a hill, or turn your ship back towards the center of the system, and you watch the sun explode and consume everything you know. How could you not ask “what are we going to do?”

But Outer Wilds’ time loop is a special sort of temporal fix, letting us have it both ways. You might only have 22 minutes to save the world, but you have that 22 minutes as many times as you need. There is never enough time, yet there is always more. Which means that for each moment that you work towards certain progress, you can spend another reading journal entries and meditating on the folly and struggle of those that came before, considering the ways in which these old decisions echoed their repercussions forward into the future. You can spend every second down to the last trying to figure out how the amazing technology of your predecessors worked, or you can stare out at the condemned clockwork of it all, taking in this incredible place that Mobius Digital has brought to life.

And so, I know I have time enough to count it as it goes by. Hanging above the Hourglass, I watch as the desert shifts between planets. I drift in the space between the twin worlds, Ash and Ember, counting the minutes and watching as sand falls.

Follow Austin Walker on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshots: Grace Bruxner and Thomas Bowker, GSC Game World, Red Candle Games -

Screenshot: Capcom -

Screenshot: Team Cherry -

Screenshot: Lucas Pope