In the run-up to Northern Ireland’s February 2017 election, following an embarrassing, damaging corruption scandal, leader of the Democratic Unionist Party, Arlene Foster, awkwardly fielded questions from journalists. “If you feed a crocodile, they’re going to keep coming back and looking for more,” she said, in response to a query about her mercenary attitude towards an Irish Language Act.

Across the room, Gerry Adams smiled. “See ya later, alligator,” he quipped, as pixellated black sunglasses fell to his face. The room erupted in laughter.

Videos by VICE

This exchange was posted on Sinn Féin’s official Facebook page, and is typical of the content regularly published by Ireland’s most famous Socialist Republicans. In the past few years, Sinn Féin has developed a considerable social media presence, boasting more followers than every other Irish political party combined. This is largely because, unlike their competitors, Sinn Féin can meme.

When Gerry Adams joined Twitter four years ago, his eccentric, quirky presence stood in comical contrast to the cold-blooded killer Irish young people were warned about by their parents and the media: he posts pictures of himself wearing a fake Dora the Explorer head, talks about trampolining naked with his dog and claims he is his own favourite rapper. Adams’ shenanigans attracted a kind of mass amused intrigue, and soon he accumulated over 100,000 followers – more than Ireland’s current Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar. Last year, he even released a book of tweets.

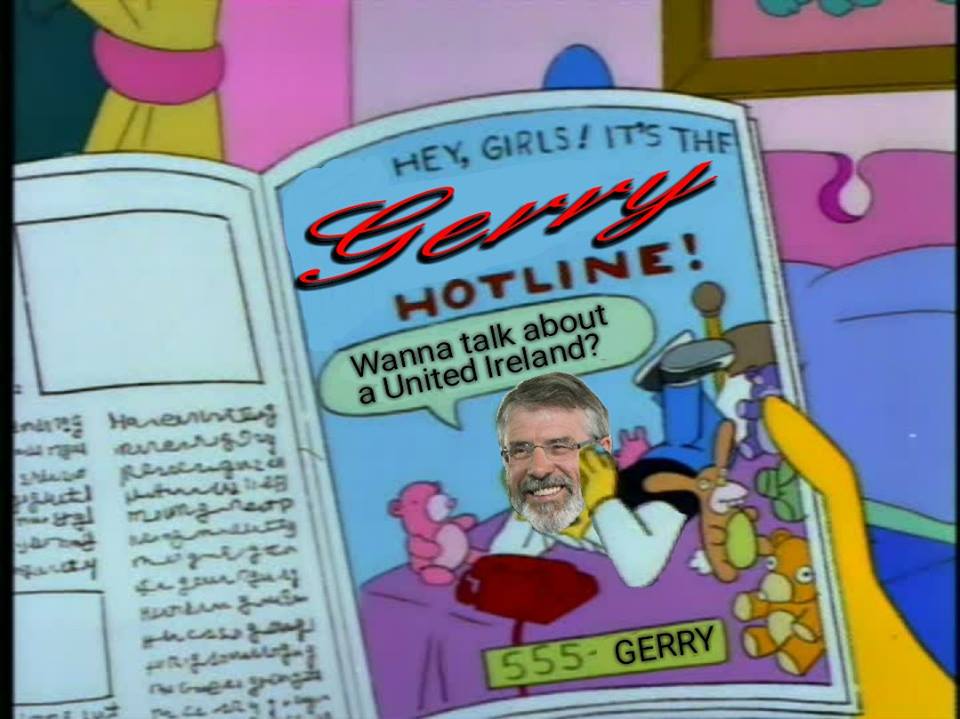

Twitter Adams’ popularity would soon result in the proliferation of “Gerry memes”. This whacky caricature of County Antrim’s bespectacled republican son, now ubiquitous on Irish meme pages like Ireland Simpsons Fans and others, enhances Sinn Féin’s PR efforts, regularly appearing on their official social media accounts. “Good heavens! Just look at the time!” Gerry says in one post, grinning and pointing towards a watch, the hands of which all say “Reunite Ireland”. “I was calling for a united Ireland before it was cool,” he says in another.

The development of Sinn Féin’s sophisticated media machine is rooted in Irish Republicanism’s history of radical publishing, from Jeremiah O’ Donovan Rossa’s The Irish People to the modern day An Phoblacht, Sinn Féin’s newspaper. According to Senator Fintan Warfield, in recent times, initiatives by Irish and British governments aimed at curtailing Sinn Féin’s political message – such as UK restrictions on broadcasting the voices of all Irish republicans – would facilitate the creation of a culture of side-stepping traditional media within the party.

Efforts were even made to prevent access to Ireland’s state broadcaster. “In 1971, under section 31 of the Broadcasting Act 1960, a Fianna Fáil minister issued an order instructing RTÉ not to broadcast any content that would promote or the activities of an organisation who engaged in violent means,” Warfield explains. “Then, in 1976, this was amended to include specific organisations, like Sinn Féin and the IRA. That ended in 1994. So, you can see the need for Sinn Féin to have had its own media team.”

Many of the young people currently at the helm of Sinn Féin’s completely in-house social media unit spent their formative years in the party’s youth wing, eventually landing jobs in Leinster House. “That’s when the memes came along,” adds Warfield.

This current PR approach is proving extremely effective at reaching out to young voters; a recent Irish Times poll found that Sinn Féin are the most popular party for people under the age of 34. Johnny Walker, auditor at University College Dublin’s (UCD) Sinn Féin society, is of the opinion that embracing Gerry memes has facilitated this increase in appeal: “During freshers week, a lot of people kept coming over and asking, ‘If we join, do we get to meet Gerry?’” he says. “I’ve met the man a few times, and you can tell he’s a bit larger than life… he’s a bit of a meme himself.” This year, Sinn Féin’s UCD freshers stand had a ‘Where’s Gerry?’ board game.

Some commentators have speculated that Gerry’s online personality is contrived, a carefully managed PR initiative aimed at humanising a figure perceived by many Irish people as monstrous. However, if this was the case, a number of social media scandals involving Adams – including an ill-advised dropping of the N-word – would likely not have occurred. It seems as though Gerry’s Twitter presence is authentic, for better or occasionally worse.

Later this month, at their annual Ard Fheis (AGM), the living, breathing Gerry is expected to reveal plans to step down as leader of Sinn Féin, after 34 years as president. He will leave a complicated legacy: while Adams’ comrade Brendan “The Dark” Hughes alleged he ordered the execution of mother of six Jean McConville, his later role in achieving the Good Friday Agreement cannot be understated. Depending on whom one asks, Gerry was either a freedom fighter or a vicious sectarian thug.

Once Adams departs, Sinn Féin will acquire yet another PR boost, and a long sought claim of legitimacy – officially, their leadership will have no ties to The Troubles. In the interim, it looks as though millennials will continue to engage with Republican Socialism through the prism of Gerry memes.

UPDATE 17/11/17: An earlier version of this article misspelled Jean McConville’s name. This error has been corrected.

More on VICE:

The Bizarre World of Ireland’s Celebrity ‘Gangsters’

The Irish Prime Minister Keeps Embarrassing Ireland and Irish People