For Westerners trying to peer in, Russia seems impossibly secretive. But to Russians themselves, their cities are sprinkled with places deemed inaccessible to the general public. Places where rockets are built and spent nuclear reactors are stored, derelict bunkers and bomb shelters— a million eerie vestiges of a bygone Soviet era. And these are the places that 29-year-old urban explorer Lana Sator inevitably finds herself drawn to.

Lana lives in Moscow, and she’s been infiltrating some of Russia’s most secretive abandoned sites and buildings for more than 10 years. This act of “urban exploration”—commonly referred to as”urbex”—is highly illegal in Russia, insofar as it involves entering private property without permission. But for Lana, it’s a hobby and a way of peeking behind the curtain and lifting the lid on the country’s unique and enigmatic history.

Videos by VICE

Speaking to VICE over email, Lana explained where her passion for abandoned places comes from, why Moscow is a wonderland for urban explorers, and how she’s dealt with the Russian authorities on the occasions they’ve caught up with her.

VICE: What is it about Moscow that makes it so good for urbex?

Lana: The Moscow region is saturated with industrial facilities. Property disputes, renovations, demolitions, and reconstructions are constantly taking place. New objects of interest appear often; old enterprises are being closed; hospitals and other institutions are being reorganised. It’s impossible to get bored here.

What are some of the most amazing abandoned places you’ve visited?

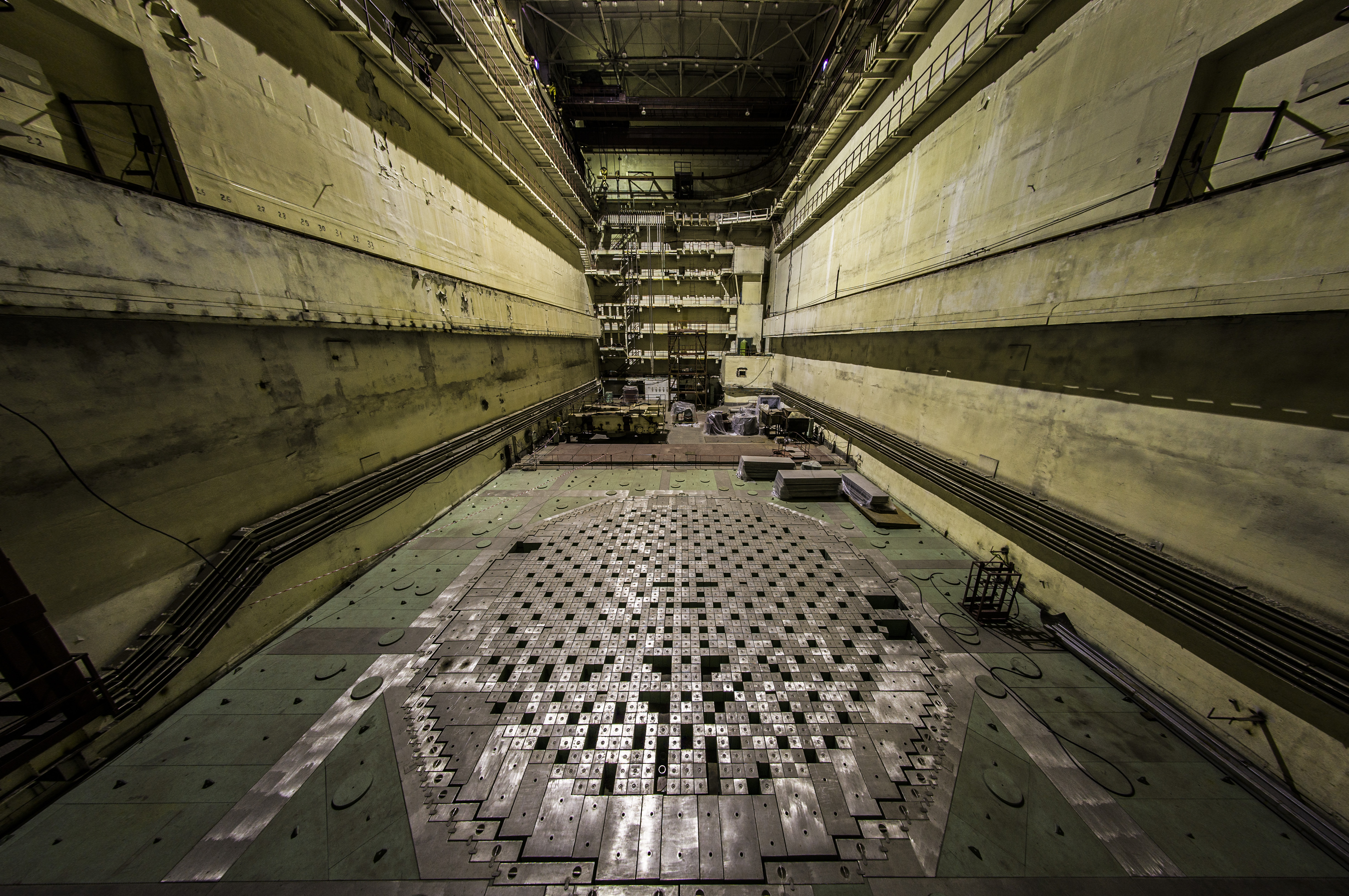

Bomb shelters and bunkers, unfinished nuclear power stations, and the underground state reserve granary. Almost all of the abandoned places are beautiful and attractive. Apart from asylums and shelters I love abandoned science labs, dead machinery, and factories.

How do you find these places?

We have a rather big urbex community, and its members share locations. We also search using satellite maps, news, archives, and some reconstruction or demolition city tenders.

How often do you usually head out to explore?

At least once or twice a month. Maximum four or five nights a week. I need this process to be happy. It’s like a drug.

When did you first get into urbex?

Two situations in my childhood defined my future interest. At the age of 11, I found myself inside an old cement factory when I shortened my way home from my grandma’s. Then at 13, me and my mother were visiting a sanatorium in Abkhazia. Abkhazia was some years after the war: the landscape and exteriors looked fantastic; destroyed and forgotten. Houses and flats after fires, holes after shootings and explosions. Rusty and knocked-over trains, cars, trucks. All of this impressed me so much that I started to love abandonments, and after about a year I understood that a part of my soul needs them. At 16 I started to take pictures of the places that I visited.

What’s the riskiest place you’ve been to?

I think unfinished nuclear power stations and stopped particle accelerators were the riskiest abandoned objects, because they’re sometimes guarded almost as much as active ones. Visiting some active territories is a great risk because of cameras and security alarms.

Do you usually explore by yourself or with a group?

We explore in a group. Sometimes the group divides, and I spend a few minutes face-to-face with the decay. I prefer to explore with guys that are older than me. Some have their own families, and the exploration is a kind of shadow life for them.

Why is there such a big urbex community in Russia?

I can’t say why it’s so big. Maybe because of soviet heritage and our love to former URRS. It’s a way of connecting to our history: touching it, feeling it.

How do you usually gain access to these abandoned places?

Russia is a republic of fences. Sometimes they have holes or strange finishings. Sometimes we need to find a way of opening locked doors or windows with no destructions.

What equipment do you usually bring with you when you go and enter these places?

I don’t use any specific equipment—just flashlights, camera and tripod, and a rope-ladder. If there’s dust I take a respirator. If the object of interest has something nuclear in its past, I take a dosimeter. Also a bolt cutter, nippers, and adjustable wrench, for removing barbed wire and unlocking doors and windows.

You’re probably most well-known for gaining access to the Energomash factory (Russian Rocket Engine Manufacturer). Can you tell us about your time there?

In December 2011 we spent five nights exploring its territory. Its fence was destroyed by some construction works. The first night we walked around the buildings outside, climbed the rooftops and towers, and looked inside the pool. The next night we went looking for a way to get inside. We found unlocked doors on the roof and fire escape, and examined one of the two test benches. A few more nights we returned to take pictures and found the entrance to the second test stand, as well as the factory museum and the bomb shelter. The bomb shelter was flooded and abandoned. I was impressed by the ascent to the tower: from the top there is a view of the whole enterprise. The company is engaged in testing space rocket engines, but there were no tests during our visits. We did not see any engines.

You run a blog and Instagram account dedicated to your urban exploration. Have the Russian authorities ever tried to contact you?

They’ve made a couple of attempts to contact me, asking me to pay some fines for illegal infiltration or help with fixing holes in perimeters. Sometimes a policeman comes and asks for reasons of my curiosity. I like the slogan “URBEX IS NOT A CRIME”, and tell them that of course I will try not to make more problems.

Can you tell us about the first-time Russian authorities made contact in person?

They didn’t know how to find me, so after the Energomash story they followed my Twitter. After I said that I was going back to Moscow, they were waiting for me in three airports. We met after the passport control, and they asked me if I am Lana Sator. I said yes, and followed them to the police office where we had a talk and I got a fine (the equivalent of five Australian dollars).

What continues to drive you to do urban exploration?

Every week I spend some hours searching places to visit. The more I do this, the more I understand how extensive the possibilities are for further exploring. Our country has a great collection of historical relics and urbex heritage.

Do you think you’ll ever stop?

Maybe I’ll stop after starting my own family. If the authorities tell me to stop exploring inside of Russia, I’ll try to continue outside.

Words by Mia Milovanovic. Follow her on Instagram.