Michael Kwet is a Visiting Fellow of the Information Society Project at Yale Law School. He is the author of Digital Colonialism: US Empire and the New Imperialism in the Global South, and hosts the Tech Empire podcast.

“Beggars” and “vagrants” are not welcome in Parkhurst, South Africa, a mostly white, middle-class suburb of about 5,000 on the outskirts of Johannesburg’s inner city. Criminals are on the prowl, residents warn, and they threaten their neighborhood security. To combat crime, the locals came up with a solution: place CCTV surveillance cameras everywhere.

Videos by VICE

However, these are not the camera networks of times past. Thanks to advancements in machine learning and AI, CCTV systems are now equipped with sophisticated video analytics that can track a wide range of behaviors, objects, and patterns, in addition to individual faces. Armed with powerful new tech, communities of color can be watched, flagged, policed, and intimidated into submission.

I’ve spent the past several years studying the video surveillance industry in South Africa. During that time, a private corporation called Vumacam has been quietly assembling a “smart” CCTV surveillance network in the suburbs of Johannesburg. Earlier this year, the company announced it would blanket Joburg with 15,000 cameras.

The story of Vumacam goes back more than a decade, with the buildup of a surveillance empire that has capitalized on advances in artificial intelligence, the deployment of high-speed internet to the suburbs, and the monopolistic dynamics of the CCTV industry. The end result is an attempt to roll out an AI-driven, nationwide CCTV network across one of the world’s most racially divided countries.

The CCTV “Revolution”

In 2014, the South African press reported that neighborhoods in Johannesburg and Cape Town would be among the first residential areas in Africa to receive fiber-to-the-home (FTTH), an initiative led by two ambitious new startups, Fibrehoods and Vumatel. The public was led to believe this was merely an extension of fiber optic internet to households craving high-speed connectivity. What they weren’t told is the fiber project was first created for high-tech surveillance.

For years, many security firms used CCTV cameras, but they were the old-school type: blurry, low-resolution cams feeding into a control room over copper wire or Wi-Fi internet, watched by a person sitting in front of a giant panel of screens. The camera feeds are too numerous and boring to watch efficiently, so human officers in the field were tasked to observe the neighborhood.

South African private security forces employ 500,000 officers—more than the police and army combined. But guards can’t be everywhere all the time, and most areas are left unwatched by authorities.

Smart CCTV surveillance, powered by AI, aims to solve this problem. Machine learning systems perform video analytics to recognize things in the video, such as objects or behaviors. With enough cameras, computers could intelligently “watch” the neighborhood and notify private security forces in real-time when the algorithm detects something it deems suspicious.

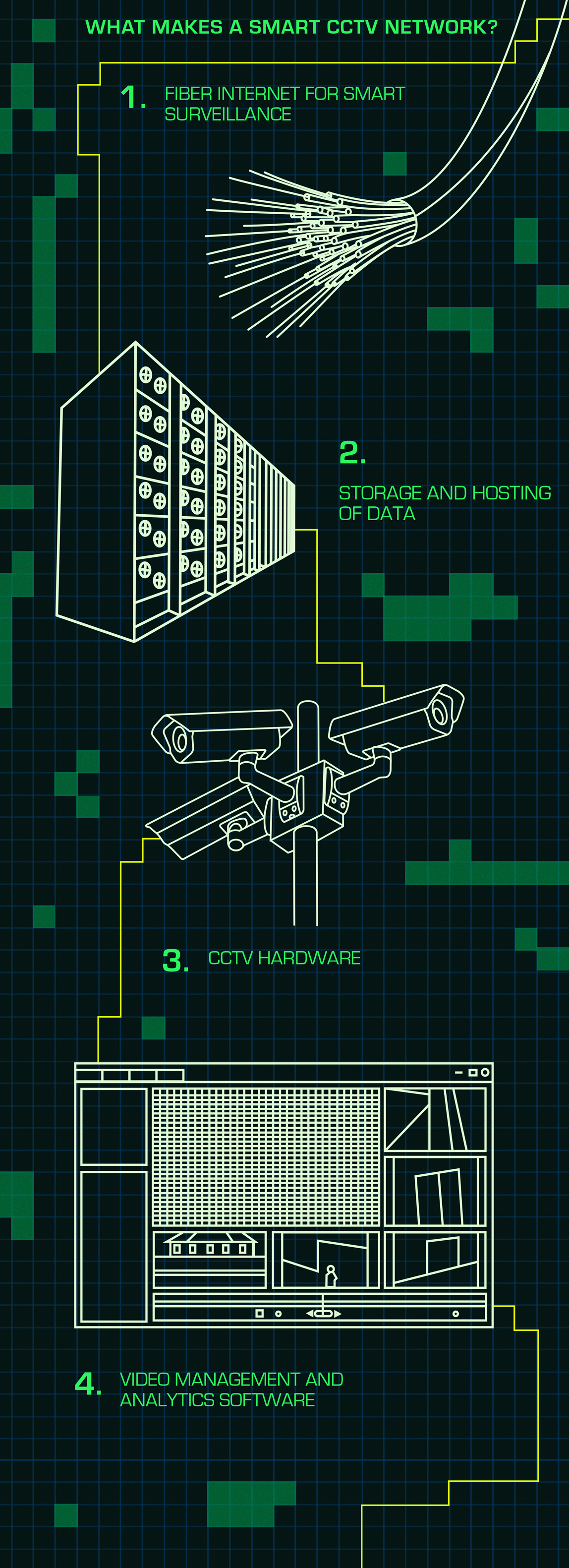

High-speed internet is critical to smart CCTV networks. For quality video analytics, video feeds must be in high-definition: Like humans, AI struggles to recognize things in fuzzy pictures. However, high-res videos use lots of data. To stream HD video to a control room for monitoring and server-side analytics, the reliable, high-speed connectivity offered by fiber optic networks is ideal.

In a 2015 documentary by the Dutch TV broadcaster VPRO, Cheryl Labuschagne, the chair of Parkhurst Village Residents and Business Owners Association, explained that “the fiber-to-the-home [initiative] was actually born out of a security need.” Parkhurst was experiencing a series of thefts and other crimes, she explained, and residents felt “using modern technology was the best way to improve safety in the neighborhood.”

Cameras would now come equipped with modern video analytics, along with infrared and thermal imaging. “We’re going to be using […] GPS technology and so on to map where incidents occur, and to map movements, and to map unusual movements,” Labuschagne told VPRO. She added: “I’m really, really hopeful that what we’ve started is a revolution.”

Johannesburg gets “smart” surveillance

This surveillance “revolution” comes in a country with a history of racial violence. From colonial conquest through apartheid, white colonizers seized African lands and forced the majority black population into segregated townships. Today, 25 years after transitioning into a neoliberal democracy, South Africa ranks among the most unequal countries in the world. Over half the population lives on about $3/day or less—and they are almost exclusively people of color. Official unemployment is at 29 percent, with 46 percent of the black population out of work. In 2018, HIV/AIDS rates reached as high as 20 percent among adults in poor areas, and citizens blame corruption and a society run by elites for a declining standard of living.

Racialized forms of inequality underscore the formation of Vumacam. Some photos and a map help us understand the rollout of smart CCTV networks:

To guard against crime, the mostly white, wealthy households of the suburbs have traditionally been fortified with high concrete walls, electric wire, guard dogs, surveillance cameras, and alarm systems. Smart CCTV networks offer a powerful upgrade to neighborhood policing.

South Africa’s foray into CCTV-based security began about a decade ago. In 2008, a Johannesburg suburb called Sharonlea became a model for surrounding neighborhoods with the introduction of high-tech cameras.

The driving force behind smart surveillance networks in South Africa is a man named Ricky Croock, the co-founder and CEO of Vumacam. Before Vumacam was formed in 2016, Croock was the CEO of a private security firm, CSS Tactical, which patrolled the streets with armed guards and vehicles, aided by CCTV surveillance. CSS Tactical was among the first companies to take a “proactive” approach to neighborhood security, rather than a “reactive” one that responds to incidents after they occur.

Croock’s first tech innovation was to blanket a handful of suburbs with cameras and integrate video analytics into private security patrols. Around 2008, Croock and CSS Tactical began using software called iSentry in their day-to-day operations.

iSentry was developed for the Australian military to detect “unusual” behavior. It works by fixing a camera to a single spot and letting it film for an extended period of time. Eventually, the software learns what to look for. It issues alarms when it determines something is “abnormal”—like loitering pedestrians or minivans—and prioritizes video streams for review by human operators in a control room.

The security guards receive prompts to decide whether an event is notable or suspicious, and they can dismiss, escalate or categorize items like “single person,” “taxi,” or “traffic incident.” Their ongoing input trains the system to determine what is “normal” for each camera. iSentry also sets digital “tripwires” to detect intruders and claims it can detect when objects have been left in busy or outdoor areas.

Vumacam incorporates iSentry, and is further aided by BriefCam, an Israeli software program frequently used to summarize the action in a video for post-incident investigations. It performs object and behavior recognition that allows investigators to compile statistics and search through videos for things like “people wearing red shirts” or “people riding bicycles.” BriefCam includes an option for facial recognition, but Vumacam says it is not currently making use of it.

The Vumacam CCTV network also performs automatic license plate recognition (ALPR). Suburbs typically place ALPR cameras around the entry and exit points, forming a virtual fence to detect who enters and exits the neighborhood.

Dreams of Monopoly Power: Vumacam’s CCTV Strategy

Behind the scenes, various business developments were pushing Johannesburg suburbs towards smart surveillance solutions. Imfezeko Investment Holdings was founded by the Croock family in 2006, and has a portfolio of around a dozen surveillance and tech-related companies, including Intelligent Surveillance and Detection Systems (ISDS), the developers of iSentry.

By 2010, CSS Tactical was expanding with its proactive patrols and iSentry CCTV solution. At the time, they operated 44 cameras in a small suburb called Dunkeld and serviced 15 Johannesburg suburbs. Then, around 2011, Croock began rolling out a fiber network to improve the CCTV network in Dunkeld. In 2013, he formed a residential fiber Internet offering called Fibrehoods.

Croock and Fibrehoods began connecting cameras through aerial fiber rollouts. As a secondary venture, Croock doubled up his revenue stream by offering home fiber connections at a time when fiber internet was not widely offered to residential neighborhoods in South Africa.

Meanwhile, a startup called Vumatel began pitching fiber internet for household use and “smart” CCTV surveillance in Johannesburg suburbs, beginning with Parkhurst in early 2014. That August, Vumatel started laying down the fiber optic cables for use by ISPs and private security companies.

In 2016, Vumatel acquired its Fibrehoods competitor. Shortly thereafter, Croock and Vumatel formed a company called Vumacam, which would be jointly owned by Vumatel and Imfezeko Investment Holdings. Vumatel would now handle FTTH rollouts, whereas Vumacam would take up the CCTV component.

Vumacam offers a video-management-as-a-service platform that collects data from video cameras. Its main source of value is not so much the hardware it leases—the video camera infrastructure—as it is the centralized repository of video data captured by the cameras. Access to the company’s infrastructure can be licensed to security providers, while the intelligence it gathers, processed by video analytics, can be sold to third parties.

Most CCTV networks cover a limited area, such as a city district or suburb. If you steal a car and drive into another suburb, you escape the local CCTV network. Vumacam changes this. Instead of each suburb operating its own isolated CCTV network, any neighborhood using Vumacam’s centralized platform feeds video into its data center. The system can then track activities—such as a stolen car or a person’s movements—across all of its CCTV networks, in real-time.

Put another way, Vumacam is creating a network of CCTV networks.

Most South African suburbs do not already have their own camera networks, so when Vumatel rolls out fiber to a new neighborhood, it also pitches the Vumacam CCTV solution. If a neighborhood has a legacy CCTV network installed—which usually features low-res cameras poorly suited to video analytics—Vumacam might offer to replace it with its own network. A resident from Hurlingham, for example, told me Vumacam “bought back our old cameras and they installed new cameras.”

As Vumacam’s network grows, each camera added to their platform makes it more valuable, because it’s being added to the Vumacam super-network. The result is a full-stack, vertically-integrated, end-to-end CCTV solution, with the fiber owned by Vumatel, and the data center and surveillance software controlled by Ricky Croock’s Imfezeko companies.

Much like Facebook, Amazon, and Uber, Vumacam’s strategy is to build private infrastructure that it can exploit to lock in consumers and establish a virtual monopoly.

Race, Class, and Video Analytics – Powered by AI

Some supporters I’ve spoken to say Vumacam’s CCTV deployment is acceptable so long as those deciding who is guilty do a fair job evaluating the evidence. Proponents maintain that smart CCTV surveillance is neutral: it will flag any person who loiters, walks suspiciously, or travels in groups, irrespective of race.

But what constitutes “abnormal behavior detection” appears to be racially biased in a region where security officers disproportionately target people of color.

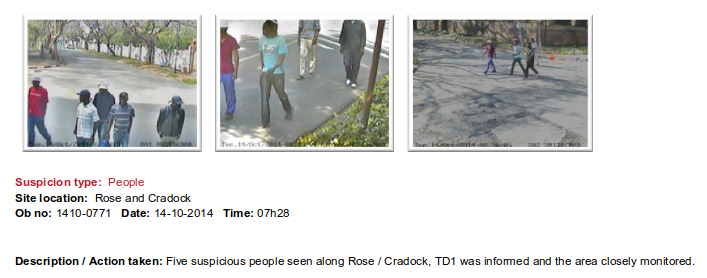

A few years ago, Fibrehoods posted a real-life iSentry “shift report,” which lists 14 incidents flagging 28 “suspicious” people in the Johannesburg suburbs. All 28 people flagged for “unusual behavior” are black, even though the majority of the suburb’s population are white. Case examples include an electrician leaving his place of work, five people walking together, a person sitting on the road, mail delivery men, and construction workers unloading bricks.

In several examples, security was notified and individuals were “closely monitored,” according to the report. In many instances, those flagged were paid laborers, or simply walking through the neighborhood.

Last year, Beagle Watch, the private security firm which acquired Croock’s CSS Tactical, published a racist advisory of “Things to look out for and remember when describing a suspicious looking person(s).” The advisory explicitly notes features like “skin tone,” “scars,” and baggy clothing as worthy of suspicion.

According to Meredith Broussard, author of Artificial Unintelligence, “it’s not surprising” CCTV behavior detection systems would disproportionately flag black and brown people, because AI is often imbued with bias by the small and homogeneous groups of engineers who create it.

“The problem with these kinds of systems is that they tend to pick up all of the underlying racist assumptions of the culture that makes the system,” she told me.

“If you train a visual system on a neighborhood where mostly white people live, then, yes black and brown people are going to look like anomalies.” And if there is biased input into the machine-learning model—say, the control room monitors are more likely to flag poor or black people as “suspicious”—then the system will replicate those biases.

During a November 2014 briefing on fiber-driven surveillance for Parkhurst, James Bowling, then security portfolio manager of the suburb, told the audience that security systems would be used “to start profiling people.” He said a security company could take pictures and digital fingerprints with a mobile touch machine, and utilize the South African Police Service and private companies to build up profiles about people who frequent the suburb. “If they become a problem,” Bowling remarked, “you’ve got a profile on them and you know who it is, and that’s how you start to bring down the crime.”

Those walking the streets are not legally obliged to respond to show papers or respond to inquiries from private citizens or security. “But when you have people in an intimidating vehicle with bullet-proof vests and big guns, it can … serve to disrupt crime,” another SafeParks speaker noted. “If they choose not to answer and not give a valid reason for being there, then there’s a reason behind it. You raise a flag.”

Six months earlier, Bowling told suburbanites that private security will stop and search people who “look out of place” and call the South African Police Service if they deem necessary. “We’re going to be profiling people,” Bowling said. “We have to start to actually control the suburb, rather than let outside people control us.”

In 2016, Parkhurst updated its SafeParks website with a message instructing its residents, “Don’t feed beggars and vagrants or give them money, it encourages them to stay in the area and some of them contribute to crime.”

Over the past decade, a handful of suburbs have deployed the iSentry video analytics solution in their communities. Most recently, Parkhurst announced it is finally ready to begin rolling out the Vumacam system, continuing the network’s spread throughout Johannesburg.

The technology’s use in South Africa recalls a harrowing past.

During the colonial and apartheid eras, the government forced Africans to carry internal passports designed to segregate the population and allocate labor according to racial quotas. Apartheid passbooks were derisively called dompas, or “dumb pass,” by the black population. The system was a staple feature of apartheid, designed to monitor and control Africans from a centralized location.

As Keith Breckenridge’s Biometric State details, police desired the ability to swiftly identify and locate “Natives” by their national ID or fingerprints contained in the passbooks. Yet the paper-based system was too frail and difficult to manage efficiently, and the dystopian dream of panoptic population control by an all-seeing state failed. Nevertheless, the consequences were brutal: apartheid cops used the passbook system to perpetrate mass violence and incarcerate the African population. Police would pull black people over, ask for their pass, and do with them as they saw fit.

Thami Nkosi, an organizer with the Right2Know Campaign—a digital rights organization similar to the Electronic Frontier Foundation—said the Vumacam system is a new form of dompas in South Africa. “As a black person, if you’re going to be entering [a Vumacam] area, you’re going to be surveilled,” Nkosi told me.

Many Johannesburg security organizations and residents associations post pictures of alleged criminals apprehended by private security forces. They are always black, and often handcuffed or pinned to the ground.

This August, television anchor and producer Doreen Morris opened a criminal lawsuit against a suburban resident in Morningside, Sandton. Morris, a black woman, had parked on public property to send an email on her phone. A nearby resident felt she was suspicious, and called private security firm Fidelity ADT, who proceeded to call the South African Police Service. The firm publicly acknowledged that Morris was parked on a public street, and did not do anything illegal.

“Had that been a white person, would they have treated her the same way?” Nkosi asked.

Smart surveillance solutions like Vumacam are explicitly built for profiling, and threaten to exacerbate these kinds of incidents. Melody*, a resident involved with a Vumacam rollout in a different suburb, told me, “with all this predictive stuff, the people who are likely to be seen as guilty are going to be the poor black people.” (Several people agreed to speak for this story only if identified by pseudonyms. They are denoted with an *.)

Violence, Crime and Fear

To be sure, crime is a serious problem in the suburbs—as it is throughout South Africa.

Despite halving the homicide rate since the 1994 elections, South Africa has some of the highest rates of murder, assault, robbery, and rape in the world. Gender-based violence is widespread. In September, thousands of people took to the streets to call for a national state of emergency after an especially deadly month for South African women.

General crime has fallen significantly since 1994, but surveys show public fear is increasing.

“If you live in South Africa, you have a constant feeling of discomfort around crime,” Mark*, a resident actively involved in a Vumacam rollout for the CraigPark Residents Association, told me. “I think the closer the crime is to your person, the harder it hits people.”

The underlying strategy driving CCTV networks is to push private security and police to cover increasingly wider areas with cameras—and in doing so, move the crime out to other neighborhoods that are not covered. In criminology literature, this is referred to as the “displacement” of crime to non-camera areas.

“Yes, you are making it someone else’s problem,” James Bowling told Parkhurst residents during a public forum about the rollout of fiber and CCTV in the suburb. But that’s exactly why pooling resources into surveillance is desirable. “Now, collectively, you’re able to push it out further”—into other communities, he said.

Security vendors like Vumacam, of course, claim their solutions help reduce crime.

Croock’s Fibrehoods touts a 95 percent drop in crime for the Dunkeld suburb, while Vumacam’s managing director Ashleigh Parry claims an 80 percent drop there. Croock recently announced, “in some areas” with Vumacam, “crime rates are down by up to as much as 30 percent (year on year).”

In reality, it’s not clear how much CCTV cameras have impacted crime in South Africa, as there are no peer-reviewed studies on the topic.

Mark told me that according to the Residents Association’s data, crime escalated 20% year-on-year in each of the last five years in the Craighall area, but “I can’t think off-hand of one [incident] where the cameras have proactively stopped a crime in the last four and a half years.” However, he said, the use of CCTVs for “post-crime analytics”—understanding “where did they come in, what did they do, how did they get to our suburb”—has been “very beneficial.”

Let’s assume the cameras make it more difficult to steal property or commit a violent crime. In this case, Brett Fisher, CEO of private security firm RSS Security Services, told me, those committing crimes “will typically move to the next suburb.”

The end result is a surveillance arms race: the more prevalent CCTV surveillance becomes, the more nearby areas are pressured to install their own camera networks. As cameras proliferate, mass surveillance becomes the norm.

The logic of mass surveillance underlies modern CCTV initiatives. If a person commits a crime and runs away, eventually they will reach a spot not covered by that camera network, and they can proceed to their getaway. If smart cameras were everywhere, people would be analyzed from the time they leave their home to when they reach their final destination. For anyone deemed “suspicious” or targeted by the system, there would be nowhere to hide.

If Vumacam gets its way, the company will soon extend its CCTV network to township areas.

In 2018, Kirsten Eddey, then Head of Marketing at Vumatel, told me that by rolling out to the suburbs, Vumatel was deepening the digital divide. In the interest of internet equality, in 2017, the company announced plans to bring fiber connectivity to the townships, starting with Alexandra—which is adjacent to the current rollout—then extending into the Diepsloot, Soweto, and Tembisa townships.

Eddey told me the township rollout “will start with fiber and then we’ll look at introducing cameras as well” through Vumacam.

This August, Vumacam announced its plan to cover the Alexandra township in CCTVs. The initiative will be undertaken with eBlockwatch, a “neighborhood watch” organization that pools information about crime from its members into a centralized database. Founded by Andre Snyman, its motto is to “use smart tech on dumb criminals.” It recently proposed an app that would use the Vumacam network to generate an alert if it thinks one vehicle is being followed by another.

Ricky Croock agreed to sponsor R 5,000,000 (~$350,000) worth of cameras for the project.

Eventually, the Vumacam network would cover “the whole of Johannesburg” with an “intelligent software layer over that network, which allows you to isolate incidents and anomalies,” Eddey said. This allows authorities to search for things like “people wearing a red shirt on this road between one and two PM on this day.”

Eddey’s description matches a conversation I had in November 2016 with a member of the Parkhurst residents’ association, who told me Vumatel was talking about blanketing all of Johannesburg in surveillance cameras.

The goal, Eddey told me, is to make the camera feeds and the software available to police and local security companies.

Vumacam is also rolling out CCTV to public schools as part of its “Kids Custodian Initiative (KCI)”, placing students across Joburg under the centralized surveillance of the Vumacam network. Vumatel provides fiber to 255 schools in the South African province of Gauteng. As I argued in my 2017 paper on tech in schools , the trend toward more surveillance could have a chilling effect on education and threaten civil rights and liberties.

In the meantime, South African suburbanites have begun pursuing new paths to expand CCTV coverage. One member of a residents’ association, Andries*, told me his community is discussing the possibility of adding their own personal CCTV cameras to a community network—what I call “plug-in surveillance networks.”

Should Vumacam (or any other network) allow residents to plug into their network, its coverage would expand beyond traffic intersections—where the company currently installs most of its cameras.

Mission Creep

Vumacam has said it “engages” with the police, but that any data requested by the South African Police Services requires a subpoena. The precise terms, however, remain fuzzy.

For example, city police may be able to tap Vumacam feeds for monitoring and investigation. They may also be able to access metadata from Vumacam’s video analytics, and then request the actual footage using a subpoena.

Like many other surveillance systems, Vumacam may also provide services beyond policing theft and violence. In 2018, Vumatel’s Eddey told me the company was “looking at other models” and “engaging with different companies [to] monetize” the service and reduce the costs of using it. For example, access to the surveillance network could be valuable to insurance companies who could “pay for the network, then we could make it available to security companies, and the police, for a very nominal fee or for free,” she said.

Eddey provided a case example in which Vumacam demonstrated its system to a skeptical insurance company. The company was dealing with an expensive insurance claim involving an alleged hit-and-run involving multiple people and injuries. Vumacam retrieved footage from its CCTV network near the site of the incident, which showed the claimant had actually sped through a roadblock and into a wall, allowing the insurance company to avoid paying.

Companies from other industries, like housing insurance, could also become clients, Eddey added.

Vumacam isn’t the only company pitching its surveillance software to private businesses. The ISDS software suite, which includes iSentry and BriefCam, advertises video analytics for property management, business intelligence, retail, mining and agriculture, education security, healthcare facilities, and smart cities.

With cameras placed everywhere, people and cars can be identified and tracked across the networks, behavior scrutinized by automated systems for security and police forces, and patterns of life evaluated by algorithms for government and corporate analysis.

Democracy, Law, and Transparency

As I first reported at Counterpunch two years ago, the deployment of smart surveillance networks in South Africa has taken place in the shadows, with little public disclosure or debate. The issue only received considerable attention this February, when Vumacam went public. A few months later, the company announced it had deployed 2,000 active cameras and that it will “blanket Johannesburg with 15,000 cameras” by year’s end, as if the rollout were a foregone conclusion.

As with the deployment of surveillance technology in schools, the South African government has been mostly silent on the topic. Members of the two major parties—the African National Congress (ANC) and the more right-wing Democratic Alliance (DA)—have shown enthusiastic support for smart CCTV networks.

In 2016, facial, license plate, and behavior recognition technologies were introduced to Johannesburg under then-mayor Parks Tau (ANC), who claimed the cameras helped reduce crime in the central business district. Writing in the Daily Maverick, Zakhele Mbhele (DA), who serves on the Police Portfolio Committee, lauded Shanghai’s “impressive” deployment of 31,000 cameras to compensate for police staff shortages—a shortage shared by South African police. The Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), who garner about 10% of the South African vote, are silent on the issue.

South African civil rights and liberties organizations like Right2Know and the recently-established LCII Foundation are pushing back against the Vumacam project, on legal grounds.

The groups contend that Vumacam is not compliant with South Africa’s Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA), a law similar to Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which was signed by the President in 2013 but has still not been brought into effect. They claim that under the law, Vumacam requires consent from individual users to collect personal information such as license plate data. Vumacam counters that their product is POPIA compliant, and that their data procedures adhere to European data protection laws like the GDPR.

Collen Weapond, one of five Information Regulators tasked with enforcing POPIA, told me “there is no reasonable expectation of privacy in public places.” If the surveillance protects the “safety and security” of the data subject, he said, then it is permissible under POPIA because it is in “the legitimate interest” of those being surveilled. Weapond also holds that always-on camera surveillance is permissible if it uses “intelligent surveillance technology” to reduce video processing and recording.

In other words, POPIA appears to permit mass-surveillance, as long as it is done in the name of security.

Similarly, Vumacam believes it has the right to spy on everyone in public all the time. In a Q&A section on its website, the company claims that, “nothing in the public space is considered private.” As soon you as you leave your driveway, they argue, anyone can capture your information, including license plates, “facial features,” and the “physical movement by people.”

Residents have criticized Vumacam for rolling out its surveillance network with little engagement from local communities. Melody told me that in the Johannesburg suburb of Emmarentia, a meeting to propose putting up cameras was facilitated by a local security company called CAP, which was buying access to the camera network from Vumacam. Only fifty or so people attended the meeting, she said.

“I don’t think everybody is on board with it,” Melody remarked. “They certainly didn’t do a proper job of consultation… Even if they did get 100% attendance of all residents in the suburb […] there are plenty of non-residents of the suburb who drive through the suburb and would be filmed on their cameras. So I would say their process of consultation is wholly inadequate.”

It is difficult to discern general opinion across the suburbs. Melinda*, a resident from another suburb, told me “we didn’t have one person come forward” as Vumacam rolled out cameras, and there was no pushback. However, Vumatel’s Kirsten Eddey told me that when approached by Vumacam to install cameras, a few suburbs refused, citing privacy concerns.

Data protection laws like the GDPR and POPIA seem poorly equipped to address mass video surveillance, which fundamentally changes the experience of moving through public space. By offering communities a system that allows all human activity to be automatically tracked, recorded, and algorithmically scrutinized, Vumacam is creating a public-private surveillance state.

New legislation could ban the use of video analytics for surveillance of publicly accessible spaces and limit the size and scope of CCTV networks.

Gavin Borrageiro, Founder and Director of the LCII Foundation, told me he supports this proposal. “Public spaces belong to the citizens and public at large,” Borrageiro said. “This kind of surveillance needs to be banned, because so many human rights can be contravened in South Africa, taking us back to the days of apartheid.”

Vumacam CEO Ricky Croock responded to inquiries about its CCTV surveillance network, but refused to go on the record.