“Leave Britney Alone!” It’s a phrase that reverberates throughout the halls of YouTube history, and also remains relevant for our celebrity-obsessed age where the power of fame has fanned out so far and wide through society that it’s practically compulsory for survival. You can probably make a better living by sacrificing your life for content, as opposed to delivering any particular good. Meltdowns are a common plot point on a career path now, and rubbernecking as public figures hit their breaking point or make a misstep is a modern day spectator sport. The internet is the friend along the way that helped usher us into this furnace of spectacle, but the thirst for intimacy, particularly with the special and talented, seems all too human—everyone wants to watch someone who believes in themselves, or, at least, can convince us that they do. Idolatry may be a sin, but worship has to land somewhere in a godless place, so the pop idol often has to report for an impossible duty.

Mima Kirigoe is introduced as an idol, a J-pop singer in a trio called “CHAM!,” and the heroine of Satoshi Kon’s debut feature film, Perfect Blue (1997). On the cusp of a career change when we meet her, she announces at one her group’s concerts in the first segment of the film that she is leaving music to become an actress. She wants to be taken seriously, or, at least, her management wants her to be, and so she has to move onto another even more elaborate charade. In the audience during her show is a strange looking man who holds his hand towards her dancing figure so that, in a trick of perspective, it looks like she’s standing in his grasp, on his palm.

Videos by VICE

Mima’s minder, Rumi, was an idol herself when she was younger, and resolves to stick around to help shepherd her protégé into acting, but constantly reminds Mima that she originally moved to Tokyo because she, the ingénue, wanted to sing. Mima forges ahead with bit parts on TV dramas, frantically repeating on set before cameras start rolling the one line of her debut role. Nothing has even happened yet, but one gets the distinct sense when watching her that she’s not safe. “Who are you?” is her line, and she seems to be reciting it to, and for, herself. She thought she could change her life, like buying a new outfit, but she doesn’t mean anything to the new creatures she’s surrounded by, except what she was before: an idol. This is her second chance, and being secondhand can often crater value. She’s not even old enough to be vintage, but the scriptwriters decide it would be fun to treat her like she’s washed up anyway, so they write a rape scene just for her.

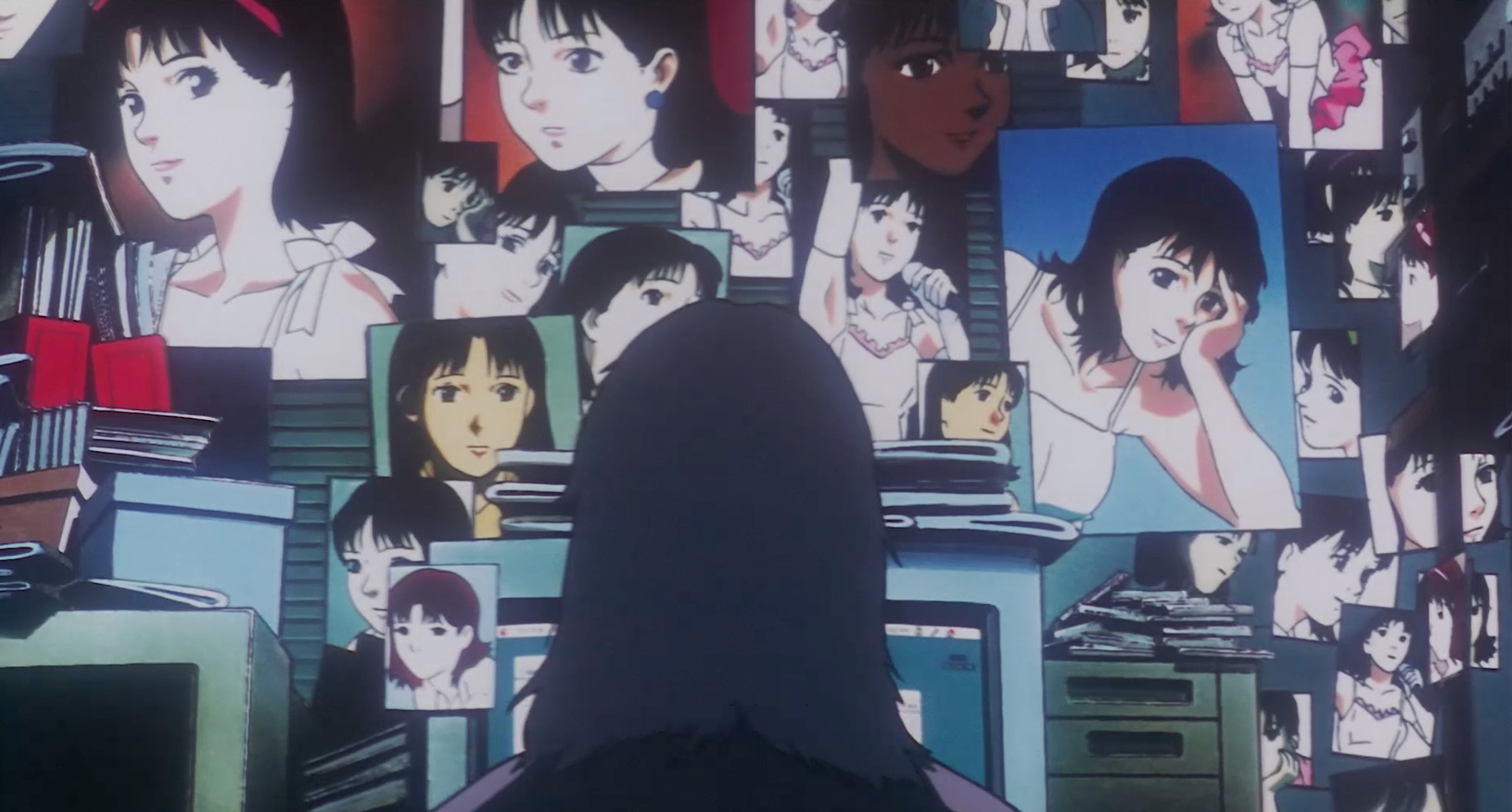

The man she noticed at her concert keeps appearing on set of her film shoots. A fan letter for her delivered to a set turns out to be a rigged explosive, and then Rumi shows Mima a website someone has set up that publishes a first-person diary of Mima’s daily activities, along with articulated desires and motivations that seem at odds with her stated wish IRL to become an actress and move on from singing. She starts to have visions of herself in the stage costume from her days in CHAM!, and that giggly ghost continues to haunt her as her management doubts the evidence of what is quickly becoming a flaming pile of red flags: Mima has a stalker. She doesn’t express this suspicion though, not when the man who wrote especially for her the role of a stripper getting gang banged turns up dead, his eyes gouged out, nor when the photographer who goaded her into taking her clothes off in a photo shoot receives death by umpteen stab wounds. There’s a bag of bloody clothes in her closet on the morning the photographer was found dead, and even though we just saw her kill him in a previous scene, the film casts doubt at almost every turn that what we’ve seen was really how it was. Her stalker might be a figment of her imagination, but is it more or less likely that being haunted by a fear of failure and having her insecurities mercilessly exploited is what’s really shredding Mima’s sanity?

Shuttling back and forth between her tiny apartment and her various jobs, usually chauffeured along the way, she starts to compulsively check in on the version of her life that the website is projecting to her fans. The story it tells about her days is sunnier than her real life, and no one in this tale is forcing her to do anything. It seemingly executes itself, but may in fact be dictated to her stalker, dubbed Me-Mania, who dutifully transcribes it for the record. She can’t contradict the narrative it presents, because it reads much better than her life does. It’s too close, it knows too much, and it might even know better than she does—her fans loved her when she was singing, now she apparently has to let herself be taken advantage of to prove she’s worthy of respect.

Eventually there’s a plot twist that ostensibly resolves who is actually gunning to take down Mima, but by then the film has already rattled a viewer’s grasp of the reality of the world it’s presenting too vigorously to make one believe that solving a mystery is the point of Perfect Blue. It doesn’t matter if you can put away an enemy, if the entire apparatus of your life—selling intimacy to the lonely—makes close interaction with anyone a dangerous game of Whac-A-Mole for the psychotics and garden-variety leeches that will swarm on over to get blood. Unhand the stars, because, honestly, you can survive without seeing them.

Perfect Blue screens on September 10 in an English dubbed version as part of a Fathom Events screening and at Metrograph in Japanese with subtitles from September 7 through September 13.