“THIS IS NOT FUN,” Dan Teitel thought.

Fallout 3 was full of computer terminals, and if a player wanted to hack one, they’d have to beat some minigame abstractly representing the hacking process. Teitel, a programmer at Fallout developer Bethesda, was, in 2007, responsible for implementing the design for that minigame, and he remembers thinking players would just hate it. “It was going to have letters that would appear on the screen and a countdown timer… yet another that would be panned by gamers as tedious and obtrusive,” he says. “I was no game designer, but I saw it as my duty to improve upon this idea somehow.”

Videos by VICE

Later that week, and still with no idea for something better, Teitel got an email from his friend Bob. “It seemed like an amazing gift from the gods… when I opened this email [with] the message, ‘Hey, do you remember this?’ along with a link to an online version of the game Mastermind.”

Teitel was in heaven. Mastermind would be fun.

Mastermind, the codebreaking-themed board game, turns 50 this year. But that’s not how old it really is, and how old it is, nobody can say. Ironically, this is a codebreaking game whose own origins can’t be solved.

If you only know Mastermind as a well-worn and underplayed fixture of living room closets and nursing home common areas, you may have no idea just how big this thing was in its early years. Invented in 1970, Mastermind would sell 30 million copies before that decade was up, and boast a national championship at the Playboy Club, a fan in Muhammed Ali, official use by the Australian military for training, and 80% ownership amongst the population of Denmark. “I never thought a game would be invented again,” marvelled the manager of a Missouri toy store in 1977. “A real classic like Monopoly.”

This was the good time.

If you don’t know Mastermind at all, i.e. you never lived in Denmark, it’s played over a board with a codemaker who creates a sequence of four different colored pegs, and a codebreaker who must replicate that exact pattern within a certain number of tries. With each guess, the codemaker can only advise whether the codebreaker has placed a peg in its correct position, or a peg that is in the sequence but incorrectly placed. According to the game’s creators, an answer in five tries is “better than average”; two or fewer is pure luck. In 1978, a British teenager, John Searjeant, dominated the Mastermind World Championship by solving a code with just three guesses in 19 seconds. (In second place was Cindy Forth, 18, of Canada; she remembers being awarded a trophy and copies of Mastermind.)

Mordechai Meirowitz, an Israeli telephone technician, developed Mastermind in 1970 from an existing game of apocryphal origin, Bulls and Cows, which used numbers instead of colored pegs. Nobody, by the way, knows where Bulls and Cows came from. Computer scientists who adapted the first known versions in the 1960s variously remembered the game to me as one hundred and one thousand years old. Whatever its age, it’s clear nobody ever did as well out of Bulls and Cows as Meirowitz, who retired from game development and lived comfortably off royalties not long after selling the Mastermind prototype to Invicta, a British plastics firm expanding from industrial parts and window shutters into games and toys.

Mastermind entered a young, fast-growing “adult games” market, where new favorites Scrabble and Monopoly vied with Chess and Go for pole position atop sales charts and coffee tables. “People would rather stay home and play backgammon, than spend $30 for dinner,” said Jock Miller, an adult games sales manager, of the phenomenon. To Leslie Ault, psychologist, chess scholar and the author of the Official Mastermind Handbook, an adult game was a lifestyle accessory (“the game can serve a party function similar to that of a plate of food, a bowl of nuts, or the liquor table”) and appealed to man’s primal desire. “[I] call it the hunting urge,” he wrote. In the modern age, “people search out their prey in the form of games.”

Ault confirmed to the Tampa Times that a sexual element was also very much in play. “A male and female locked in combat in a tense game can create an emotionally charged situation,” the Times summed up. “Marketing tactics, such as the outer covers on games that feature a man and woman facing each other across a table with knowing looks, exploit the sexual turn-on theme.”

Mastermind slipped comfortably into the adult game canon. Invicta flooded the market with deluxe, miniature, braille, children’s, grand, royale and electronic variants (“It is reasonable to expect that people playing Electronic Mastermind will be mistaken for hard workers laboring over their calculators,” predicted the Louisville Courier-Journal,) and, appallingly, a “solid gold edition” with “a diamond-studded shield and coloured pegs of hand-cut stones—jet, ivory, amber, coral and lapis lazuli.” In 1978, this cost $29,000 (or, adjusted for inflation, “class warfare.”)

If you ask Ault, the secret of Mastermind’s success is straightforward. It’s easy to learn, plays quickly, requires no translation and rewards mathematical analysis and strategy, e.g.: “If the Codebreaker is thinking out loud or putting some trial Code Pegs on the board, don’t react. If necessary read a magazine or otherwise occupy your mind.”

There’s also, Ault wrote, a deeper attraction. “In the modern world the average person is constantly reminded of his own powerlessness—the threat of global disaster from bombs, pollution, germ warfare, or what have you; the impact of far-away events such as the Arab oil policies; the many abuses of ‘big’ governments against life and liberty; and the worsening of problems such as crime and social unrest for which there seem to be no clear or effective answers. Unlike most games, in Mastermind there is an answer, one single correct hidden code.”

What’s also important, I think, is the aesthetic that Meirowitz and Invicta applied to the Bulls and Cows framework. Specifically, the cover. Adorning the original Mastermind box was the portrait of a woman, dressy and unimpressed, leaning behind an older gentleman, suited and seated, fingertips pressed. Or, to defer to the commentators of the era:

- “a slinky female and a mysterious chap” (Les Gelber, president of Invicta’s American branch

- “an aloof, bearded, red-headed man and [an] Eurasian beauty. The arts editor asked me who they were…. He said he knew and it would be important to the story” (Patricia Rice, St. Louis Post-Dispatch)

- “Clearly he thinks you will never crack his secret code…. will she too sneer at your failure, or perhaps be impressed with your success? [They] represent the rich international power elite who control much of the destiny of nations; or, more abstractly, the powerful forces threatening and to some extent controlling our lives. By playing Mastermind and solving the hidden code, one is symbolically outsmarting such people or forces, thereby compensating for the virtual inability most of us have to control the real world around us.” (Leslie Ault)

Those powerful forces were Cecilia Fung and Bill Woodward; respectively, a computer science student at the University of Leicester, and the owner of a chain of Leicester hair salons known locally as “Mr. Teasy-Weasy.” Woodward later switched nicknames to “Mr. Mastermind,” claiming he even bore that title in his passport. (Fung did him one better, taking as her married name “Cecilia Masters.”)

You don’t see Mr. Teasy-Weasy and a self-described “impoverished student” on the cover of Mastermind, nor the woman crouching behind Fung to hold her too-large dress in place, nor the urine stains on Woodward’s trousers from an attempt to photograph a cat in his lap. You see in these anonymous and well-dressed figures—directed, Masters recalls, to look “demure and mysterious”—a suggestion of “the international power elite.” You see mystery, and a question inherent in that name, Mastermind—is he the mastermind? is she? are you? Mastermind’s aesthetic treatment was well-timed for the era of James Bond, John le Carré and congressional investigations into the clandestine activity of intelligence agencies. It’s a case for the power of the image, or narrative design: with a name and a cover photo, Invicita transformed Bulls and Cows into espionage and intrigue, and a Teasy-Weasy into a Mastermind.

While Bill Woodward continued to pose for the covers of successive editions of Mastermind, Cecilia Masters had no further involvement, though not for lack of interest on her part. After the photo shoot, Masters did not hear from Invicta, but did happen to run into one of the agents who had selected her. He promised to contact her, but again, Masters heard nothing. “I started to notice my flatmate always ran to the post box every morning before me,” she remembers. “I found out later she was destroying letters from the studio.”

Masters’ flatmate, a fellow computer science student, was with her when she was approached for the photo shoot, and Masters thinks her flatmate may have been upset that she was not chosen instead. “She said she was curious [about] the results of the photo shoot and once she opened and destroyed the first letter to me, she had no choice but to keep on destroying all further correspondence.”

“I was very upset about the whole incident.”

Mastermind is itself a costume for an older and frankly more mysterious game. Most people don’t even know its real name. It might be known as “Bulls and Cows” if you go searching for it, but most people who learned the game as children don’t remember the name they called it. There’s no record of why it’s called that or how old the thing is. It could have been invented by a T-Rex. And I think to properly understand Mastermind requires understanding Bulls and Cows—they are, after all, basically the same—so I’ve gone back as far as possible to solve this mystery.

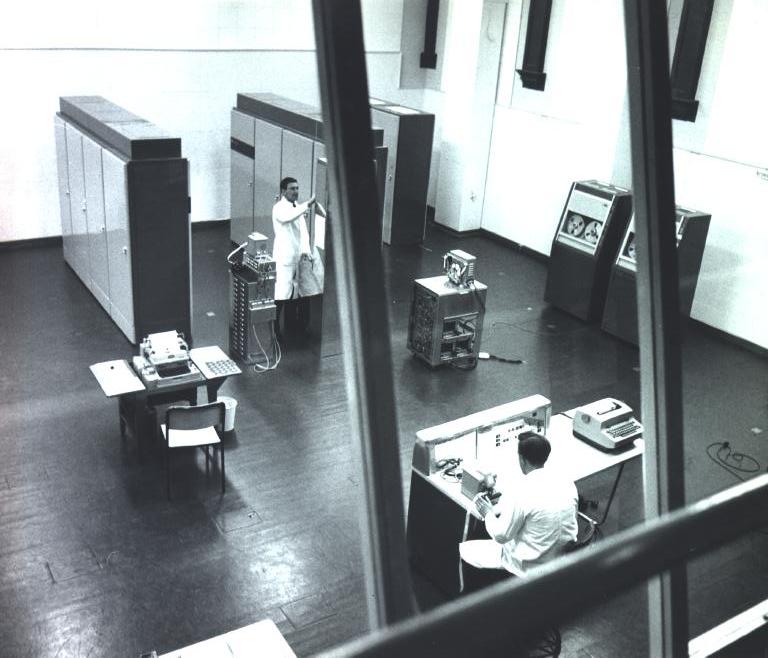

The earliest reference to Bulls and Cows is in the work of Dr. Frank King. In 1968, King was studying for a PhD in electrical engineering at Cambridge University and looking for something to implement on the university’s Titan computer, which had recently been equipped with Multics, a time-sharing operating system allowing multiple users to access one computer concurrently and remotely.

Thinking a game would be enjoyable, and something more sophisticated than Tic-Tac-Toe even better, King wrote a version of a childhood puzzle. “Good grief, you’ve implemented Bulls and Cows,” he remembers other students saying, though he called it MOO.

King also wrote in what was then a new feature for computer games: a league table, or leaderboard, on which players could record their score. “For the first few days people vied with one another to get higher on the league table,” he says. “People were clearly getting better and better, and then someone was at the top of the league table with an impossibly ridiculous average.”

It was a new kind of security vulnerability against which the operating systems of the day had no inherent defense. If a MOO player was allowed to update one of King’s files—specifically, entering their name and score in the league table—they could, in theory, just as easily input a fake score, delete another user’s score or even change the source code itself.

King’s hackers would come clean, but every time King tried to fix the vulnerability, he’d be hacked again. “This was a very friendly ‘war,’” he clarifies. “No trying to say ‘I’m better than you are,’ no oneupmanship. Everyone was cooperating [to improve the system.]”

Nonetheless, King, distracted by his PhD, fell behind the hackers’ efforts, prompting an intervention by the attention of Cambridge’s then-informal computer security group, who told King that the problems he was dealing with in MOO were “going to be very important in the future.” If allowing a user to update a MOO league table with their own score opened the door for them to make unwanted changes, the same thing could happen to a bank allowing a customer to make remote electronic withdrawals. Both, as King explains, are just users making changes to someone else’s file.

Cambridge’s computer group was able to secure MOO, but only by hiring the hackers. (One hacker refused to explain how he’d broken MOO until he was threatened with a ban from the computer; he then ended up working at Cambridge for 50 years.)

“Very late in the day, people like IBM realised this was something they were going to have to do for their own PC. IBM mainframes in the late 1970s weren’t properly secure,” King remembers. Cambridge bought an IBM computer and, using the fixes developed for MOO, worked to improve the security of its operating system; thus, the DNA of Bulls and Cows today can not just be found in video games like Fallout (and Neverwinter Nights, and Sleeping Dogs) but basic computer security features.

Now this is the bad time.

Leslie Ault remembers Mastermind falling apart abruptly. After the prodigal teenager John Searjeant ran the table on the first two international championships, Ault was asked to find a chess player who could defeat him at the third, in 1979 in Rome. Then, with no warning, the whole event was off. “It was my impression that market craze had run its course, that the market had become saturated,” Ault says. Just as quickly, the author of the Official Mastermind Handbook closed the chapter. “My first wife was staying in California, leaving me a single parent in Jersey… and my father was dying of prostate cancer,” he tells me today. “[Mastermind was] interesting while it lasted, but with other things to occupy my attention I moved on.”

Even Denmark, with its near-universal Mastermind ownership, apparently tired of the game. I spoke to multiple Danes who agreed that Mastermind, after a hot decade, simply cycled out of fashion in the early ’80s. (One woman, however, remembered “some kind of scandal that killed the popularity… something about it… hypnotizing you or something.”)

Unlike a game of Mastermind, there’s no one correct answer to explain this decline. Oversaturation and endless variant versions couldn’t have helped (famously, Icarus was warned not to make a solid gold Mastermind) and that oversupply was probably spurred on by Invicta’s inability to recapture Mastermind’s success elsewhere. Titles like Omar Sharif Teaches You Bridge and Ouija (“Invicta says that playing the game is a way to develop the latent psychic powers that everyone possesses”) did not do the job. Invicta itself was wound down and its assets sold in 2013; the toy giant Hasbro now controls and licenses the intellectual property.

Today, Mastermind continues to be produced, by a division of Goliath Games, but no version available today features Bill Woodward or Cecilia Masters on the box. Both were replaced some time ago with a product photo of the game board itself. The writer Richard McKenna describes the current Mastermind as “packaged in a riot of abstract bright colors that screech “toy,” all traces of its previous incarnations—rooted in ideas of success and power that have shifted hugely since the game first appeared—now erased.”

When Woodward and Masters’ enigmatic, diffident stares are out of the picture, you realize just how much of the work they were doing to give the thing an identity. At 50, Mastermind no longer aspires to be a chic lifestyle accessory or an invitation to battle the powerful global elite. It’s a toy, now indistinguishable from its knock-offs. It’s Bulls and Cows.

It strikes me that checking in on just about anything after 50 years is a pretty rude thing to do. I thought of this when I spoke to Leslie Ault, who recalled attending Mastermind tournaments at the Playboy Club for me in between visits to his wife at her dementia care home. Bill Woodward passed away in 2013; a family friend told me Woodward was “a fine gentleman” and that his adult daughter had died in a horrible accident. Cecilia Masters had a successful career as a developer of banking software; now semi-retired, she has traveled the world and operates several holiday cottages in East Sussex. Mastermind, she says, did not have much impact on her life, though she does wonder “if life may have been more exciting if my friend had not destroyed my letters from Invicta.”

Mordechai Meirowitz, after inventing Mastermind, got involved early with an educational program for gifted children, Odyssey of the Mind. I asked Odyssey of the Mind what they could tell me about Meirowitz, and they didn’t remember anything.

Mastermind still exists, but a 50th anniversary doesn’t serve to celebrate the game as much as emphasize its decline—and to remind you that, by the way, everyone dies.

Frank King doesn’t really remember where he learned Bulls and Cows, the game that leaped from his subconscious and into Cambridge’s ancient Titan computer.

He was just always aware of it, he says. “I played it as a child in the 1950s. I must have played it at primary school.” He wonders if it’s coincidence—and thinks it probably is—that the person from whom he remembers learning Bulls and Cows was the child of a dairy farmer.

Is it possible that Mastermind evolved from some kind of traditional farm game? Siobhán Gleeson, who grew up on a farm in County Cork, Ireland, doesn’t really think so, but offered a theory to explain the name why Bulls and Cows was ever an appropriate name for a game of numbers and taxonomies. “Maybe it had something to do with cattle tags? Like the ones that are on their ears? I keep one of our old ones in my jacket pocket as a reminder of my [late] dad which is why it came to mind. Maybe when this game came about only bulls had ear tags with numbers?” Gleeson brought up the puzzle to her sister Marie. Marie recognized the puzzle but didn’t know it had a name, and couldn’t remember exactly how she learned of it.

In a game of Mastermind, there is always an answer. “One single correct hidden code,” Leslie Ault wrote: a gift in a mysterious and disordered world in which “the average person is constantly reminded of his own powerlessness.” But in answer to the question of where Mastermind came from, I’m really leaning, in the absence of other evidence, towards “it’s just something that farmers know.”

But I think—contrary to the spirit of the game—there’s something satisfying in the mystery. To think of Mastermind not as an intellectual property with a defined legal creation, but as one face of an apparently immemorial puzzle of mysterious origin that has spread throughout history and culture like a meme, with no owner or master.

It’s tempting, anyway, to think of Mastermind not as a brand, but an idea, which is ageless. Because otherwise, it’s something that can turn 50, and so it’s something that can die.