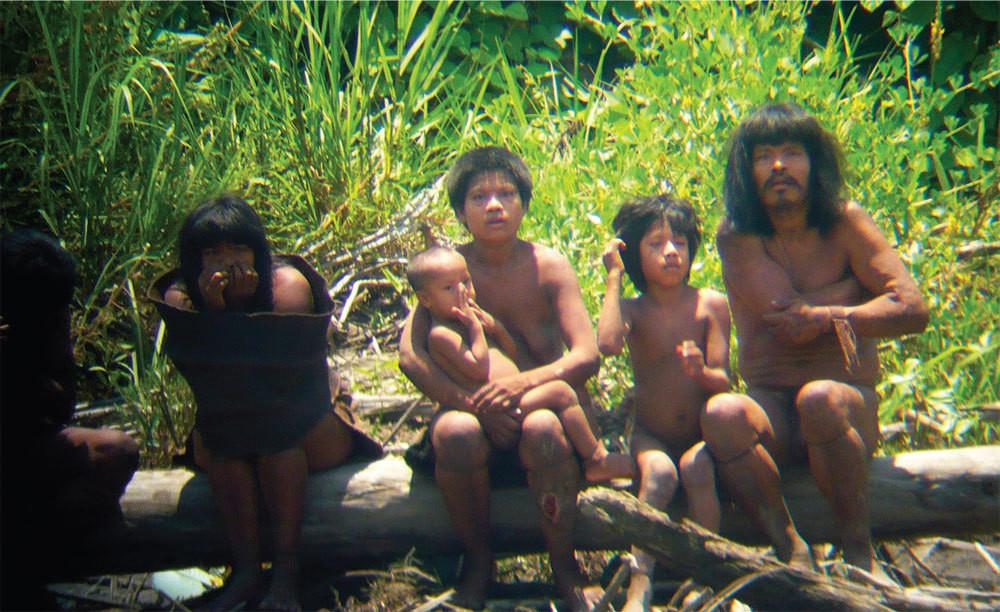

Photo courtesy of Stringer Peru/Reuters

This article appears in the September Issue of VICE

Peru recently announced plans for its first official contact with the Mashco-Piro people. Local officials had long opposed interacting with the group, one of Peru’s 15 uncontacted tribes, which know of the wider world but remain aloof from it. By breaking its policy of nonengagement, Peru may set a precedent with big ramifications for the world’s dozens of other isolated peoples.

Videos by VICE

Peru claims it’s initiating contact because the tribe is already reaching out—in troubling ways. Since 2011, the Mashco-Piro have approached “contacted” villages, sometimes killing residents and pillaging supplies. Their advances are escalating, with around 100 sightings reported last year, including raids that forced two indigenous villages to evacuate and led to the death-by-arrow of a boy in a third village. Locals suspect that incursions onto Mashco-Piro land by illegal loggers and miners are leading the tribe to desperate measures. Meanwhile, missionaries and “human safari” tourists are leaving gifts for the Mashco-Piro, either out of pity for their perceived poverty or in a bid to tempt them into the modern world. Whatever the reason, these gifts could carry diseases to which the isolated tribe has not been exposed. At this rate, the government thinks it’s the only group that hasn’t entered the Amazonian fray.

Some academics support Peru’s “controlled contact” plan, provided the government offers long-term aid to protect the tribe. University of Missouri anthropologist Rob Walker wishes that Peru had reached out even earlier, preempting dangerous informal outreach programs. “A good template is that the government steps in before the rest of the outside world shows up,” he said.

Even Survival International, usually an anti-contact activist group, believes that Peru needs to communicate with the Mashco-Piro in the current circumstances. Still, the organization fears that controlled contact could give the nation pretext to resettle the tribe, develop its lands, and encourage other nations to pursue similar courses of action. (Peru has a history of exploiting uncontacted lands, which in the 1980s led to an interaction between Shell and the Nahua that wiped out half the tribe.)

Walker agrees that tribes should have the protection to initiate contact on their terms, coercion-free. But the number of uncontacted peoples reaching out in recent years suggests that in many cases we may be too late to provide security. Necessity dictates that we’re bound to see more controlled contacts soon.

Follow Mark Hay on Twitter.