This article appears in VICE Magazine’s October Prison Issue

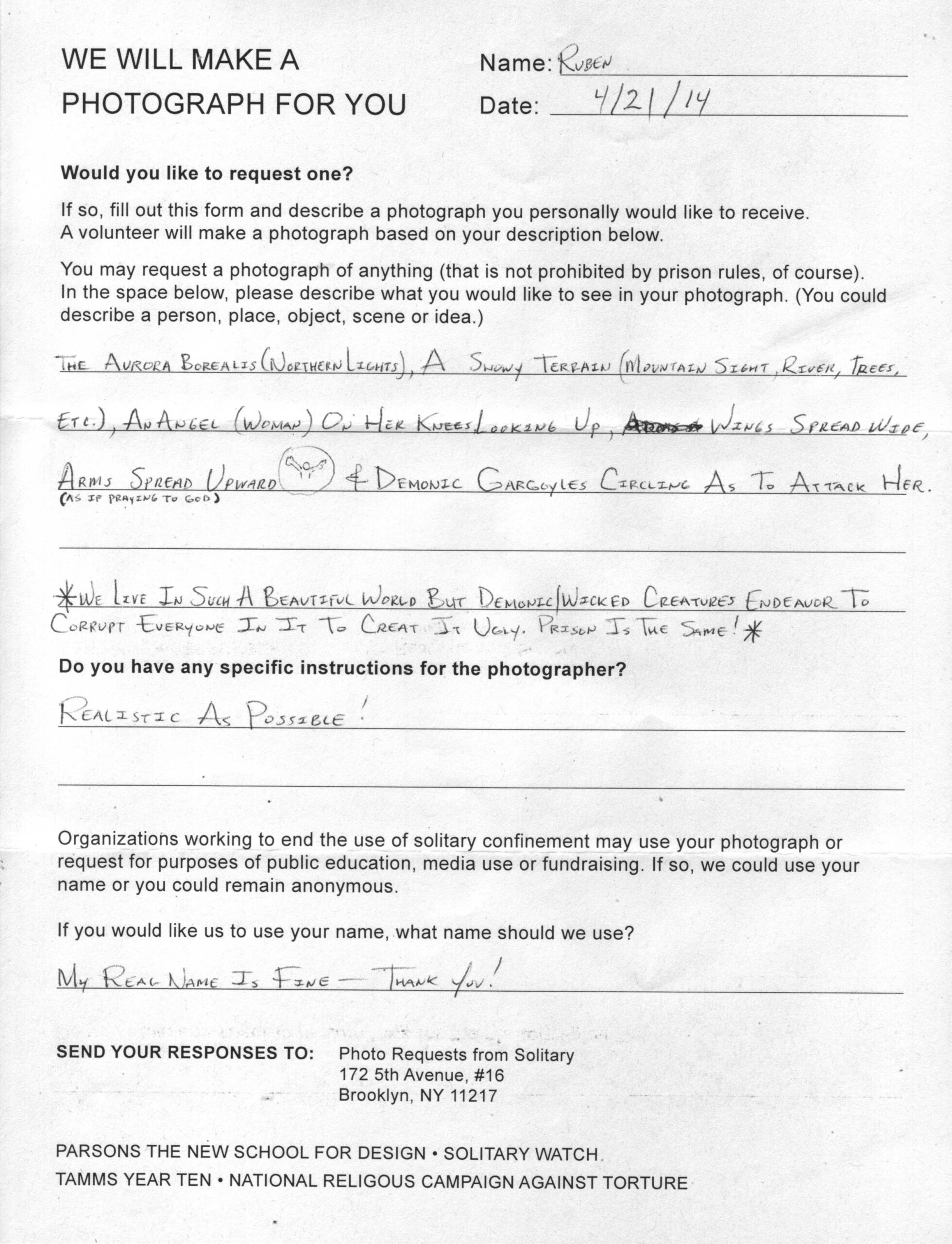

Over the past few years, Photo Requests from Solitary has invited men and women in solitary confinement to request a photograph of anything—real or imagined—and promised to find them an artist to make the image. The variety of requests they’ve received is astonishing: ranging from “a picture of my family in St. Louis” to “a gray and white horse rearing in weather cold enough to see its breath.” The pictures offer a new way to think about people in isolation. We don’t see what prisoners see, but what they envision. Taken together, these requests provide an archive of the hopes, interests, and memories of people in the “hole.”

Videos by VICE

Though foremost a form of support to people in isolation, the project has also helped advance campaigns to abolish solitary confinement. PRS was started in 2009 by Tamms Year Ten, a grassroots coalition initiated a year earlier to campaign for the reform or shuttering of Tamms prison in Illinois. A year after the coalition’s inception, Governor Pat Quinn introduced a reform plan, and in 2012, he proposed closing the facility.

In spite of tremendous opposition from the guards’ union and downstate legislators, Tamms closed in January 2013. That year, PRS collaborated with Parsons School of Design, Solitary Watch, and the National Religious Campaign Against Torture, expanding its efforts to prisoners in California and New York.

For our Prison Issue, VICE reached out to PRS in hopes of assigning some of the requests to our contributors. Some were simple, like one from Christopher (California): “Can the photograph be a photo of my daughter?” Others required a bit more imagination, like one from Robert (Illinois): “At 66 yrs. of age I try to use a little humor: I want a picture of a trash can with the lid half off and 2 eyes peeking out of the half open lid as the trash can is rolling down the hill toward an incinerator with the caption: ‘I seem to be picking up speed I must be headed towards a bright future.’”

Our hope is that some of the issue’s visuals, generated by and for inmates, offer a better understanding of the vagaries of the confined.

Photo by Jason Altaan

Photo by Fryd Frydendahl

“Daddy’s Angel.”

Photo by Edward Cushenberry

Photo by Matthew Leifheit and Ole Tillmann

Photo by Keisha Scarville

“I seem to be picking up speed I must be headed towards a bright future.”

Photo by Michael Marcelle

Photo by Anthony Tafuro

Photo by Molly Soda and Zoe Ligon

Photo by Keisha Scarville