Illustration by Dan Evans

Twenty years ago today, a young man from America’s largest housing project, Queensbridge in New York, released a record that changed the face of hip-hop forever.

Videos by VICE

Nas began recording Illmatic when he was 18. It came out when he was 21 (it was almost canned by the label because it took so long) and even within an era of hip-hop defined by the hunger of youth, it’s staggering. It immerses you in claustrophobic Queensbridge and paints vivid canvasses of the frontline of America’s domestic wars on crime and drugs. Yet it remains a deeply personal record, ultimately about young man trying to find his way.

Featuring a dream team of producers (Large Professor, DJ Premier, Pete Rock and Q-Tip), Illmatic picked up a haloed five-mic review in hip-hop bible The Source, with the reviewer Shortie concluding: “I must maintain that this is one of the best hip-hop albums I’ve ever heard. Word.” Jay Z describes Illmatic as a “blessing and a curse”, as in: where is there left to go when your debut record is regarded by many as the greatest hip-hop record of all time?

In the foreword to 2009’s Born To Use Mics, which sees scholars, rappers, poets, writers, and filmmakers reflect on Illmatic, Common captures a sense of the indefinable X factor that separates the great from the good: “Illmatic was brilliant. His lyricism, his storytelling, his control on the mic, that production. Illmatic had all the elements, but it was greater than the sum of its parts. It had that something else – that rawness, that realness, something you could feel but not say.”

Co-edited by scholars Professor Michael Eric Dyson and Associate Professor Sohail Daulatzai, Born To Use Mics points towards Illmatic as a landmark record worthy of academic research and theorizing. In a recent conversation with Nas at Georgetown University, Professor Dyson, places Illmatic alongside Hemingway and Homer.

For Sohail Daulatzai, who runs classes on Early hip-hop from the mid-1970s to 1995 at the University of California, it’s the defining document of that period. Sohail wrote the liner notes for Rage Against The Machine’s 20th anniversary box set and the DVD of Freestyle: The Art Of Rhyme He’s also the author of Black Star, Crescent Moon: The Muslim International and Black Freedom Beyond America. Noisey sat down with a hot brew (it probably should have been Courvoisier) for a Skype session with Sohail to pick away at hip-hop and academia and what Illmatic can tell us about America? We hope you’re sitting comfortably, because the answer is a helluvalot.

Noisey: Hi Professor. I think we can both agree that Illmatic is pretty darned tootin, but what does hip-hop bring to academia?

Sohail Daulatzai: There’s a generation, myself included, that grew up with hip-hop. By the time we reached our early 20s and made our career choices, hip-hop was part of who we were. For those of us that decided to write a PHD, hip-hop informed what we were doing, not only our approach and posture, but the subject matter itself.

Hip-hop gave me a worldview and I take that with me everywhere I go. Even if I’m writing about something that has nothing to do with hip-hop, hip-hop informs my approach – which is to reject traditional academic theories and instead focus on the ideas of everyday people. In academia, there’s this “theory-object” distinction and I’m interested in turning it on its head and that came from hip-hop. Hip-hop inverts that hierarchy, so instead of looking at how power speaks to every day people, I look at how people speak back to power.

Right, but you can’t just answer an English Lit exam with “poetry, that’s part of me, retardedly bop”. So how, specifically, does a cultural movement like hip-hop influence a school of thought?

Erik B & Rakim, Boogie Down Productions, Public Enemy, Kool G Rap, NWA – these were the artists that shaped my identity as a person of colour growing up in the United States, where I was subject to racially motivated attacks.

The overt political posturing of BDP, Public Enemy and NWA taught me so much – Chuck D talking about the Black Panther Party and hearing about Malcolm X for the first time, hip-hop got me to open that book. It shaped my political consciousness, and gave me a way of understanding this place called America that I live in and ask questions like, what is its history? What is it doing right now to minority communities? It gave me a critical and political stance in high school that I’ve carried with me ever since.

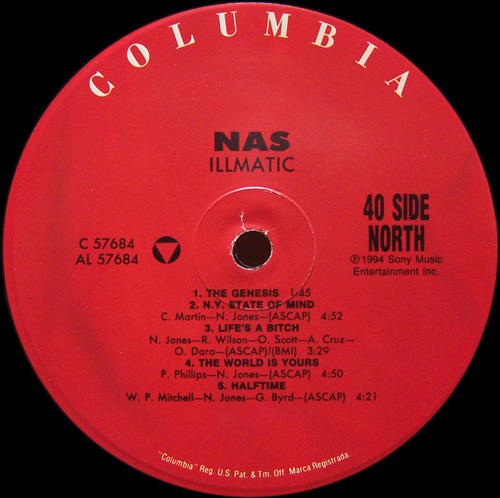

Illmatic isn’t divided into Side A and Side B it’s “40 Side North” and “41st Side South” – they are the boundaries of the Queensbridge project where Nas grew up. So it’s a sonic map, that’s about about space, geography and the housing project – for Nas it’s the Queensbridge project – but more broadly housing projects and the violent forces that created them.

When Nas centres in on Queensbridge, to me, he’s forcing us to look at why the housing project came about and why hip-hop emerged – which had to with the containment and confinement of black people and the poverty that was imposed upon them.

So let’s look at the conditions that created housing projects: in 1964/1965 the Civil Rights Voting Act passed – now according to the law, America is a free place – everyday segregation and racism are eliminated and everyone is considered equal. Yet within a year or two, hundreds of cities experience urban rebellion and black power emerges in the late 1960s. Vietnam was key in the black power movement – black power felt America was an imperial aggressor against non-white people both abroad and domestically.

For the American establishment, this is alarming. So there was a counter insurgency to destroy these black radical movements in the late-1960s/early 1970s, through a host of violent measures including state repression, COINTELPRO [a covert counter intelligence program] and the assassination of Black Panthers. Then there was the white political backlash to black power –– led by Reagan and the war on crime and war on drugs: these establish the idea there is a criminal element in America and they will destroy America and become ways of undermining and containing black rebellion and ensuring it never rises again. Prisons also emerge: today America has the largest number of prisoners in the world. The state of California where I’m from and live has the fifth largest population in the world. This move of mass incarceration is a concerted effort to contain black and brown people and reflects a racial logic and white anxiety that has defined America since its inception.

To come full circle, hip-hop is a response to this, it’s urban America speaking back to post civil rights repression, militarisation of urban communities, the rise of the prison, and the infiltration of crack and weapons into these areas to create a violent geography. There were different responses – KRS One and Public Enemy, raised consciousness, other rappers like Kool G Rap, who is one of my favourite rappers and is the precursor to Jay Z, he’s giving us intimate portraits of street life, what it means to survive, he’s not thinking in these grand manifesto ways that Public Enemy did.

It’s no coincidence at the time Chuck D called hip-hop “the Black CNN” it was pirate radio and guerrilla cinema, a space for young black and brown youths to articulate their suffering and survival in this very violent place called America. Hip-hop is the one triumphant answer to emerge.

How is the Queensbridge project Nas talks about in Illmatic connected to those wider themes?

Based on the power of America, globalisation, the free market and neo-liberalism, the world has always been New York. So when Nas centres New York in the housing project and the violent forces that created and maintained them, I think about how does this suffering connect to suffering around the world and housing projects like tenements, shantytowns and refugee camps? How were they created, what are the forces that create and maintain them?

On “New York State of Mind”, Nas says “I think of crime when I’m in a New York State of Mind” – for Nas New York isn’t this cosmopolitan global city of sophistication and allure. He speaks of violence, resistance and survival and when you begin to think about, ‘What is New York? What is America? What is Wall Street?’ you realise America maintains its power through exploitation of the Global South or Third World whether through IMF/WTO loans, creating civil wars, invasions and backing of dictators.

So I feel there is a connection between Nas and tenements and shantytowns in Palestine. For example the track New York State of Mind allows me to explore the local and the global: the local was in the midst of this authoritarianism era, where survival was the name of the game. It was a situation where bootstrap capitalism, jackboot militarism was the norm, and this situation while not exact is similar to situations in the global south whether Kabul, Baghdad, or the Gaza Strip.

Illmatic allows us to think about Pelican Bay, the largest prison in California and Guantanamo Bay – so we can see America is exporting incarceration, which has already been practised on black and brown communities in America. There’s a scene in Gangs of New York when Daniel Day Lewis says, “the rule of law must be upheld especially when it’s being broken.” He’s saying you have to uphold the law when the powerful are breaking it – gangster films really play with this, with the outlaw figure, like the Godfather, revealing the poverty of law.

Law isn’t an instrument of justice it’s an instrument of power – whether it’s the War on Crime – creating the fear of the black criminal, or the War on Terror creating fear of the Muslim terrorist, laws are created to maintain power and establish who belongs and who doesn’t, who’s a threat and who isn’t and what activities are legitimate and illegitimate.

That’s what laws are: American can take oil from another country and sell it in America and that’s legitimate, I can wear clothes made in a sweatshop in Bangladesh – that economic process is legitimate, it’s capitalism.

But other forms of economic activity are deemed illegitimate, and Nas points out how perverted and wrong this is.

Isn’t that projecting too much onto the record? I don’t remember much on Illmatic about Palestine or oil – is not even discussed.

When art enters the world, people make different meanings out of the art based on who they are – some people like certain songs, others don’t.

Different characters speak to different people – why is it black and brown youth identify with Scarface, why not a James Cagney gangster figure from another era? Because Tony Montana was a racial other, he spoke a different language.

When it comes to art, the way we make meaning is based on our own experiences and ideas that we bring to bear on it. So we should resist the temptation, to allow meaning to reside in what the artist intended because that doesn’t allow the listener any authority or agency make sense to them. That’s why hip-hop doesn’t need university or scholars to make it legitimate, hip-hop never needed the stamp of approval, it’s serious and legitimate in its own terms.

Once it is in the university classroom, it’s important that it’s resourced and supported in the same way as other disciplines. For example Illmatic is part of my Early hip-hop class, so I periodise hip-hop, the early period is mid-1970s to 1995. So in the same way the English novel is periodised and we can say at this point it went through these ideas and these genre conventions, I feel hip-hop is the same.

If Picasso has his blue period why can’t Nas have his period of artistic ideas? If James Baldwin is considered worthy of study then so are Nas and Rakim – they are writers and theorists of the world in which they exist. Edgar Allan Poe gives us an insight into a particular era of London, with a dystopic vision, in the same way so did Nas – Illmatic is a powerful lens to understand New York, America, and its relationship with the world at that moment.

Is Illmatic, the greatest hip-hop LP of all time?

It’s between Illmatic, Public Enemy’s It Takes A Nation Of Millions, Ice Cube’s AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, Wu Tang’s Enter the 36 Chambers, they are all canonical. On different days, I’ll listen to them and change my mind – Illmatic is definitely in the top three or four, a lot of the time it’s No.1

In early hip-hop, manifesto hip-hop was what people wanted. After The Chronic and Snoop the industry changed, there were fears over the black revolutionary and the figure of the gangster was celebrated instead. Nas grew up in that conscious era of Public Enemy, Brand Nubians and Rakim, then in the early 1990s Dre, Snoop and Mobb Deep come along, while Gang Starr were in between – both street and conscious raising – Nas brought all of this together. He was influenced by the overtly political and the deeply personal politics of resistance and rebellion, and crafted a unique way of talking about, which is why we’re still talking about it.

Illmatic XX is out now

Nas performs Illmatic at Lovebox in July

Celebrate The 20th Anniversary of Nas’s ‘Illmatic’ With An Exclusive Track and Illustrations