Nintendo: one of the world’s top fantasy-smiths, creator of products with truly planetary pull, from Link’s and Mario’s many outings to the newest horizon of Animal Crossing, a video game released in the middle of a lethal pandemic that somehow managed to sell twenty-two bazillion copies anyway. (Okay, twenty-two million as of this August, but still.)

Also Nintendo: gimmicky toys, instant noodles, a taxi service, and a by-the-hour “love hotel” in downtown Kyoto.

Videos by VICE

Nintendo didn’t always have the Donkey Kong-sized reputation it enjoys today. You might know that Nintendo can trace its origin back to 1889, when a mom-and-pop card company called “Nintendo Karuta” launched in a Kyoto suburb. This Nintendo was a humble purveyor of paper hanafuda (literally, “flower cards”) used in a traditional game of chance. But how did Nintendo transform from a supplier for gamblers into the family-friendly pop-cultural powerhouse it is today?

One might be tempted to cite Mario’s creator Shigeru Miyamoto, who rightfully takes the spotlight for designing Nintendo’s first superstar character. This is true, but Miyamoto wasn’t the firm’s first hit-master. The original turnaround king was one Gunpei Yokoi, an engineering whiz whose gadgets kept Nintendo afloat in the late Sixties when it was a struggling toymaker, and who oversaw the company’s pivot into video games in the late Seventies. Yokoi, more of a garage tinkerer than a computer geek, was uniquely positioned to realize that the best programmers didn’t necessarily make the best game designers.

In many ways, Miyamoto—who’d originally been hired as a graphic designer and couldn’t code at all—was another of Yokoi’s creations, painstakingly crafted and released into an unsuspecting world. In a certain sense so are we all, our dreams forged on the anvil of his hardware, realities inflected by the fantasies they delivered. Every time we switch on our Switches or simply glance down at our smartphones we are, in a real way, paying homage to the original grabbers of eyeballs and fast-forwarders of downtime that Yokoi pioneered.

The pocket-sized Game and Watch series of LCD games. The D-Pad. Light-guns and Robotic Operating Buddies. The producer of classic titles ranging from Donkey Kong to Metroid, Tetris, and Dr. Mario. And most of all, the Game Boy, which singularly transformed the way the planet spent its leisure time, whether in the schoolyard or aboard Air Force One. All of them his brainchildren, or delivered into the world by him.

All of it started with a “mercy hire” in 1965, as he explained in his yet-untranslated Japanese autobiography, Gunpei Yokoi’s House of Games (co-authored with journalist Takefumi Makino in 1997.) All of the rest that follows is taken from that book, interviews with colleagues conducted by myself and others, and an article Yokoi penned for the newsmagazine Bungei Shunju that same year.

The game of hanafuda had been a popular pastime in 1889. By 1965, when Yokoi came on board, it was decidedly old-school, and not in a retro-fun way. The most stalwart hanafuda holdouts were old fogeys and yakuza gangsters, who employed the cards in a traditional high-stakes game of chance. (In fact one theory holds that the word “yakuza” derives from the name for a losing hanafuda hand.)

An electrical engineer by trade, Yokoi joined Nintendo straight out of university in 1965. The way he saw it, it’d been something of a mercy hire. A middling student at best, he’d watched his classmates land plum jobs at all of the same big electronics firms whose interviews he’d washed out of. Nintendo wasn’t Yokoi’s first or even third or fourth choice. He’d applied out of sheer desperation—it wasn’t even an electrical engineering position. His only duty was keeping creaky the old hanafuda presses oiled and running. Yokoi didn’t care. “The main thing was I didn’t want to leave Kyoto,” he confessed. “My thinking was if I could work in peace until retirement, anything was fine.” It wasn’t particularly difficult work, and Yokoi found himself with almost as much time on his hands as he’d had when he was unemployed. He started building toys.

In middle school, he’d constructed a portable HO-scale train diorama so elaborate that a national modeling magazine came all the way from Tokyo to profile him.

Yokoi joined Nintendo at a very odd time in its history. Longtime president Hiroshi Yamauchi was in the process of dragging the old-fashioned card company into the modern era, kicking and struggling. Just 22 when he was tapped to take over the family business in 1949, Yamauchi upended the firm’s entire business model by switching to Western-style playing cards in 1953. In an effort to appeal to children, he’d hit on the idea of making a set with Disney characters. Yamauchi flew to California for the licensing negotiations, where Roy Disney gave the young CEO a firsthand look inside a burgeoning multi-media empire. Yamauchi liked what he saw.

Declaring himself dedicated to “business as an adventure,” Yamauchi plowed Nintendo’s growing profits into a bewildering array of business escapades over the course of the Fifties and Sixties. Some made a lot of sense, such as producing Mah-jongg tiles, or importing popular foreign puzzles and games; Japan got its first taste of “Twister” thanks to Yamauchi’s handiwork. Others felt a little off message, like the joint venture to sell instant noodles and rice. And a few were totally off the wall, such as the taxi service, or when Yamauchi acquired a by-the-hour hotel intended for customers having romantic trysts.

Adventure indeed. Yamauchi deserves credit for thinking outside the box with sex and noodles, but if he wanted to go big—and Yamauchi always, always wanted to go big—he needed something that would give his firm traction, build a name like Disney had for his namesake. Fortunately for this literal dealer in cards, Yamauchi had a figurative ace up his sleeve. It was a young man by the name of Gunpei Yokoi.

The Ultra Hand was been Yokoi’s idea. Maybe “idea” wasn’t the right word. He’d been screwing around in Nintendo’s machine shop when he came up with the thing. It was a simple gadget, a zig-zaggy contraption that accordioned out like some kind of Looney Tunes gag when you squeezed its handles together.

Yokoi had always loved making things. In middle school, he’d constructed a portable HO-scale train diorama so elaborate that a national modeling magazine came all the way from Tokyo to profile him. The Ultra Hand was inspired by a doohickey he’d built out of wood around the same time. Now, with access to the company machine shop, he could make his childhood daydream come back to life. “It’s a simple enough thing to make if you have access to a lathe. I made one and was playing around with it when the president got wind of what I was up to.” Yokoi glumly reported to Yamauchi’s office, fully expecting to get chewed out. Instead Yamauchi told him to turn the thing into a product—with one condition. “‘Nintendo is a game company,’ he says to me. ‘Make it a game.’ Make it a game? All it did was accordion in and out!”

Yokoi racked his brains to come up with some kind of added play value. The best he could do was propose packaging it with a set of ping-pong balls and cups, so that kids could have stacking competitions. It wasn’t much, but it was enough for Yamauchi—and, apparently, the kids of Japan. Nintendo ended up selling 1.4 million of the things, its first real hit outside of the card business. Yamauchi knew a good thing when he saw it. He founded a new R&D division and installed Yokoi as the head.

Over the next decade, Yokoi produced toy after toy for Nintendo: an electric batting machine, a mechanical driving game, an extendible periscope, a galvanometer repurposed into a carnival-esque “love tester” for couples, a walkie-talkie that used light beams instead of radio, a low-cost knock-off of Lego bricks, even a remote-controlled vacuum cleaner—the great-granddaddy of the Roomba. A few were modest hits, but many others were costly disappointments, one in particular nearly catastrophically so. Yokoi’s “Laser Clay” system, the precursor of every light-gun game to follow, was an ingenious but costly conversion kit that transformed bowling alleys into virtual skeet shooting ranges. Lavishly advertised in a campaign featuring action star Sonny Chiba, the first test locations attracted a huge amount of media coverage when they opened in the spring of 1973. Then an oil crisis hit. As citizens agitated over spiking prices and shortages eschewed entertainment in favor of rioting over toilet paper, the corporate customers Yamauchi had lined up cancelled in droves. Nintendo plunged five billion yen into the red. It would take years for Yamauchi to dig Nintendo out of the hole. If he could dig Nintendo out of the hole.

Inspiration struck Yokoi on a business trip. “I was on the bullet train,” he explained. “I noticed this bored salaryman playing with his calculator. That’s when it hit me: I oughtta make a tiny game for killing time.” As Yokoi mulled over the idea back at his desk at Nintendo, a sudden request came in. It was the head of human resources. Yamauchi had a meeting downtown, but his chauffeur had come down with the with flu. The only other person in the company who knew how to drive an American car, with its steering wheel on the left, was Yokoi.

At first he was furious. “I took pride in being a department head!” he recalled. “I wasn’t anyone’s driver!” But in a hierarchical, traditional company like Nintendo, there was no refusing the boss. Quietly grumbling, Yokoi climbed behind the wheel. But—wait a second. With Yamauchi trapped in the back seat, Yokoi was free to evangelize his idea without calling for an official meeting. “If we can make a game machine as small and thin as a calculator, salarymen can play games without getting busted! I said. Yamauchi was listening, but he didn’t show any sign of being interested.”

So much for that bright idea. Then, a week later, Yamauchi called Yokoi into his office. An executive from the electronics company Sharp was there. “I had no idea what was going on,” recalled Yokoi. “Then the boss says, ‘You wanted to make a calculator-sized game machine. Sharp’s good at that, so I called them over.’ It turned out that at that meeting I’d driven him to, the boss ended up sitting next to Akira Saeki, president of Sharp, the world’s biggest manufacturer of calculators, and he’d talked to him about calculator-sized games. Then things started moving very quickly.” The fortuitous chain of events resulted in the birth of the Game & Watch in 1980: the size of a 3×5 card, with a little LCD screen for playing a single simple game. The firm would launch more than fifty editions over the next eleven years, but perhaps its most lasting achievement wasn’t on-screen at all. It was the distinctive cross-shaped control pad included on later models—the inspiration for every Nintendo D-Pad on every console to come.

When the American game industry imploded in 1983, thanks to Atari’s all-in gamble on a poorly-designed game based on the movie E.T., the Japanese game industry experienced a mini-crash of its own as Game and Watch sales cratered. By that Christmas, Yokoi’s brainchild was out; the Famicom, later to be re-envisioned as the Nintendo Entertainment System, was in.

Yokoi watched as new hires he’d trained began basking in the spotlight of even bigger successes than he could have imagined. One was Shigeru Miyamoto, who Yokoi had personally coached through the process of developing Donkey Kong, even down to specifying the concept it was based on: a 1934 cartoon short called “A Waking Life,” starring Popeye the Sailor Man. (Originally conceived as a licensed Popeye game, negotiations with the rights-holder stalled, forcing Yokoi and Miyamoto to re-fashion Popeye, Bluto, and Olive Oyl into Jumpman, Kong, and Pauline.)

The Game and Watch had been a hit, but the Famicom, released in 1983, was proving something else altogether. The combination of the Famicom and Miyamoto’s 1985 Super Mario Bros. was like “fuel on the fire of the fad,”in the words of engineer Masayuki Uemura. Released hot on the heels of a government ordinance that banned children and teens from arcades, Super Mario Bros. became a social phenomenon. Its strategy guide actually topped Japan’s bestseller list for two years running in 1985 and 1986—a sales feat not even the likes of Haruki Murakami has ever come close to matching.

Yokoi continued producing games as the head of what was known as R&D 1, but he never stopped dreaming of creating a successor to the Game & Watch. Finally, in the late Eighties, technology caught up. Yokoi’s Game Boy, released in 1989, did for video gaming what the Walkman had done for music in 1979. No longer would gamers be tethered to their home televisions. With the Game Boy, they could play anywhere, anytime.

Also like the Walkman, which was originally derided for being unable to record, the Game Boy wasn’t state of the art technology. Yokoi called it “lateral thinking with withered technology.” In other words, don’t look ahead: think sideways. The best way to create a hit product was by using proven, off-the-shelf parts. (That these parts were far cheaper to procure than bleeding-edge components certainly didn’t hurt the bottom line, either.) In contrast to the cutting-edge, full-color portable machines released by competitors, like Atari’s Lynx, the Game Boy featured a monochromatic display with a sickly green tint and a noticeable blur whenever characters moved quickly. Yokoi had agonized over that little screen, growing so stressed at one point that he stopped eating, earning him a diagnosis of acute malnutrition. “I considered it my biggest failure,” he confessed of his inability to perfect a better screen at the time. “At one point, I honestly contemplated suicide.”

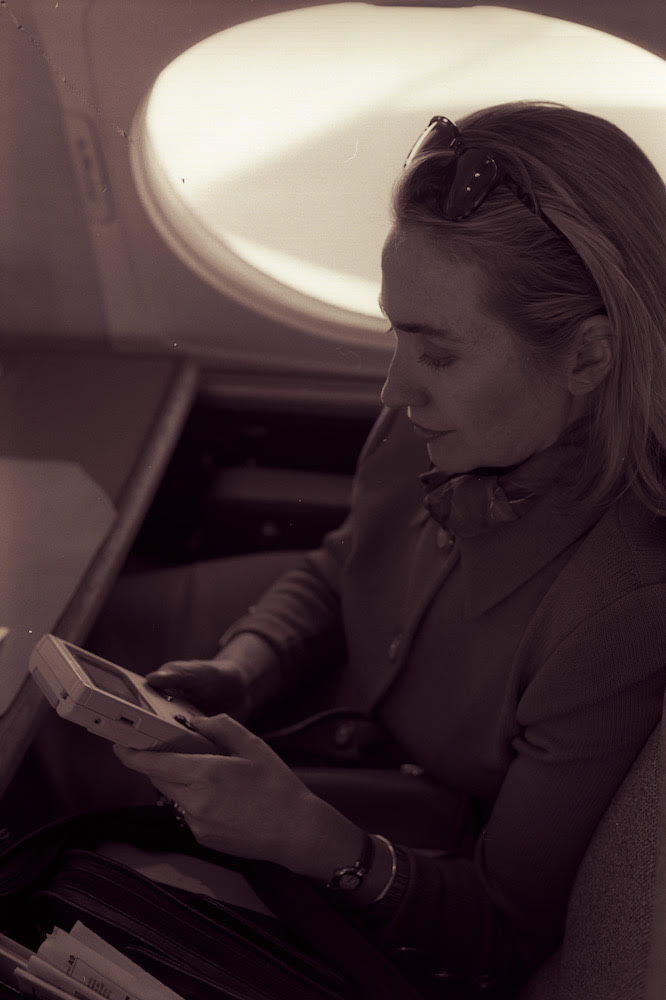

It’s hard to imagine, because in nearly every other way, the Game Boy proved the superior product. It was stylishly designed, it boasted a superior battery life, and—key for any portable electronic device used by kids – it was nearly indestructible. (One specimen, carried into Kuwait by an American GI during the first Gulf War, kept working even after being melted to near oblivion in a bombing.) Yokoi cannily grasped that kids didn’t really care about the specs—they craved the games, in this case scaled-down versions of already-huge hits like Super Mario Land. or Castlevania: The Adventure. Outside JapanIn the West, the Game Boy came with the puzzle game Tetris—the textbook definition of a “killer app” that made legions of gamers out of those who’d never imagined picking up a controller before, including one President George H.W. Bush (photographed playing while recovering from surgery) and First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton (photographed playing aboard Air Force One.) And perhaps most importantly, the Game Boy provided the platform for a literal monster of a series to take over the planet: Pokémon. The very first title in the franchise came out at the tail end of the little system’s lifespan in 1996.

In the summer of that year, Yokoi did the unthinkable for a salaryman: he quit, fueling speculation that he had actually been fired for the commercial failure of his follow-up to the Game Boy, the Virtual Boy. He quickly quashed the rumors. “I’m 55,” he wrote in an article for the news magazine Bungei Shunju, finally able to speak freely after years of being a salaryman cog in the Nintendo machine. “I want to work independently. I have absolutely no feelings of resentment towards Nintendo.” He launched a development company called Koto Laboratories, which planned—and eventually did—release a portable system called the WonderSwan. But Yokoi would never see it reach the shelves. He was struck and killed by a passing car after a fender-bender on the Hokuriku Expressway in the fall of 1997. His tombstone was inscribed with the dates of his top creations, starting with the Ultra Hand and leading up to the Game Boy.

As a result, Yokoi never got his moment in the spotlight, never got the recognition he deserved as an architect of our dreams. But in a way, this was exactly what he wanted. Like a craftsperson of old, he was content to see his products find their niches on their own merits. “People at Nintendo always used to ask me, ‘why don’t you put your name out there more?” he wrote in his autobiography, published the year before his passing. “But to my thinking, if a game I made pleases the customers, that’s satisfaction enough. If people want to look deeper and find out who made it, let them.”

Matt Alt is the author of “Pure Invention: How Japan’s Pop Culture Conquered the World.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

Screenshot: Netflix -

Screenshots: YouTube/PlayStation/Nintendo of America -

Screenshot: Rare