This article originally appeared on VICE Switzerland

During and after World War II, thousands of Jewish people fled to Switzerland, which remained neutral throughout the war. Today, around 400 registered Holocaust survivors still live in the country – though many of them kept their Jewish identity hidden for years after the war ended, out of fear of further persecution.

Videos by VICE

In 2014, Anita Winter – the daughter of two German Holocaust survivors – founded the Gamaraal Foundation in Zurich. The charity aims to provide emotional and financial support to survivors, while using their first-hand experiences to educate today’s young people about the war. The foundation’s latest project, The Last Swiss Holocaust Survivors, combines personal accounts of the Holocaust with portraits of the survivors, shot by photographer Beat Mumenthaler.

“The survivors kept telling me that something like the Holocaust could happen again,” Anita Winter explained to VICE Switzerland. “It’s everyone’s responsibility to uphold the motto of ‘Nie Wieder'(Never again).” Anita hopes that the exhibition, which is touring universities and art galleries across Switzerland, will remind a younger generation of the importance of tolerance.

Scroll down to see photos and read personal testimonies from a few of the last Swiss Holocaust survivors.

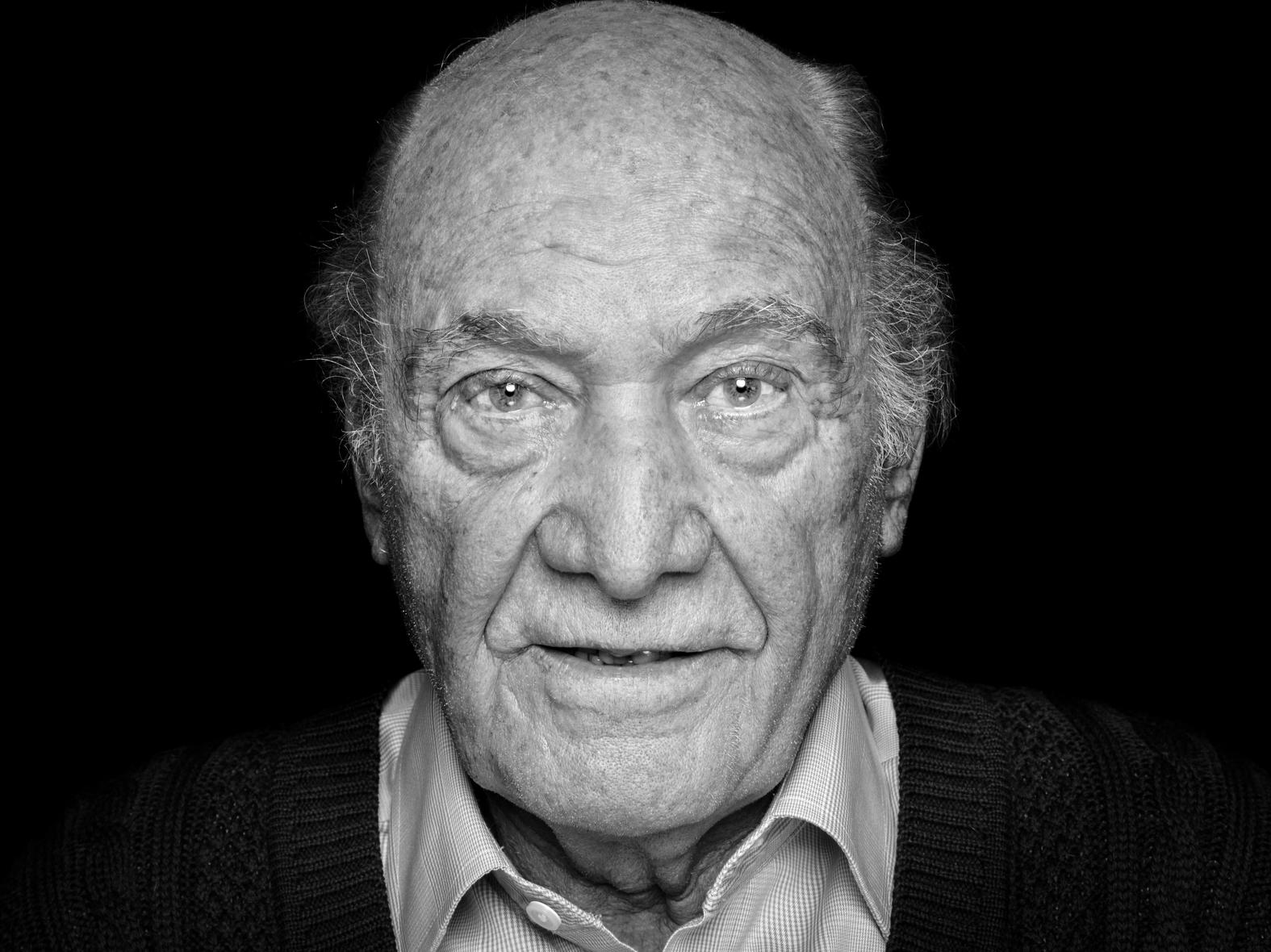

Eduard Kornfeld

Eduard Kornfeld was born in 1929 near Bratislava, Slovakia. He was taken to Auschwitz and several other concentration camps. On the 29th of April, 1945, he was freed by American troops from the Dachau camp in Germany, weighing only 27 kilos (60 pounds) at the time. His mother Rosa, his father Simon and his siblings Hilda, Josef, Alexander and Rachel were all murdered in the camps. Kornfeld arrived in Switzerland in 1949 and was nursed in Davos for four years as he recovered from severe tuberculosis. Later, he trained to become a gemstone setter in Zurich. He has two sons, a daughter and seven grandchildren.

“We were deported in a cattle car, the journey took three days. When the train suddenly stopped, I heard someone shouting outside in German, ‘Get out!’ I looked out of the carriage and saw SS officers beating people they thought were moving too slowly. A mother wasn’t moving quick enough because she was trying to take care of her child, so the SS officers took her infant and threw him in the same truck they put the old and sick. Those people were sent to be gassed immediately.”

Nina Weil

Nina Weil was born in 1932 in Klatovy, a town that’s now part of the Czech Republic. She was living in Prague, when she was arrested and deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp in 1942. A little later, she was sent to Auschwitz with her mother Amalie. She was 12 years old when her mother died of exhaustion. After the war, she and her husband left for Switzerland, where she worked as a laboratory assistant at the University Hospital in Zurich.

“I cried so much when they tattooed the number ‘71978’ on my arm. Not because of the pain, but because of what it signified. I had lost my identity and become just a number. My mother tried to calm me down by saying that when we’d get home, I’d go to dance school and get a big bracelet so that nobody would ever see the tattoo. I never went to dance school or got a bracelet big enough to hide it.”

Klaus Appel

Klaus Appel was born in 1925 in Berlin. After his father, Paul, and his older brother, Willi-Wolf, were arrested and sent to Auschwitz, he and his sister came to England in one of the last Kindertransports. After the war, Klaus married a Swiss woman, moved to western Switzerland and worked as a watchmaker. He died in April of 2017, leaving behind two children and three grandchildren.

“We were at home when the doorbell rang. They had come to arrest my father. ‘Are you Mr. Appel?’ they asked him. ‘Then come with us.’ My father just calmly turned to me and said, ‘You are going to school.’ That was the last thing he ever said to me. I never saw him again.”

Christa Markovits

Christa Markovits was born Krisztina Barabás in Budapest in 1936. The whole family converted to Catholicism before the war, but were still considered Jews under Nazi racial laws. Throughout the war, she was hidden along with her sister in a monastery in the city. In 1956, she moved to Switzerland where she studied Physics and worked at the Paul Scherrer Institute – a science and technology research centre, north of Zurich.

“It was complete luck that I had the chance to hide in that monastery. My cousin, aunt and uncle were all murdered. I didn’t deserve to survive. I didn’t deserve to be so fortunate.”

Egon Holländer

When the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp was liberated in 1945, paediatrician Robert Collis was there, and wrote about Egon Holländer in his memoirs. Collis describes the young Egon as: “a little white-skinned Slavonic child of about six years who lay very quietly in his cot. He neither moved nor spoke. He’s had typhus; he was all skin and bones.” Egon’s mother Elisabeth died of of typhus in the camp. In 1968, Egon, a qualified engineer, moved to Zurich and worked in a senior role at a technology company. He is married with two daughters and three grandchildren.

“By the time the British troops came to liberate us, I was practically dead. What I can remember most from the camp is the mountains of corpses. It’s not something you can ever forget.”

Eva Koralnik-Rottenberg

Eva Koralnik was born in 1936 in Budapest. Her mother, Berta, had lost her Swiss citizenship when she married the Jewish Hungarian Willi Rottenberg. Eva managed to flee from Hungary to Switzerland in October 1944, together with her mother and her six-week-old sister, Vera. For many years, she ran the literary agency Liepman in Zurich. She is married, has a son, a daughter and four grandchildren.

“When we arrived in Vienna, we were picked up at the train station by the Gestapo to spend a night at the famous Hotel Métropole, which was the secret service’s headquarters at the time. Harald Feller [a Swiss diplomat who rescued many Hungarian Jews] had arranged for us to stay there, right under their noses. My mother spent the night in fear and panic. I remember the polished boots, the German Shepherds on the leads and the huge swastika above the entrance to the marble hall.”

Bronislaw Erich

Bronislaw Erich was born in 1923 in Warsaw. He survived the war under a false name, as a labourer on a German farm. His father Nachum, his mother Brandl and his younger brother Jacob were murdered – presumably in 1942 in either the Warsaw Ghetto or in the Treblinka extermination camp. Bronislaw later moved to Switzerland. In 1961, he was hired to work for a printing company and he later became a supplier of polygraph machines. He is married with two children, five grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

“When I go to bed and turn off the light, I think of my parents and my little brother, who were all murdered. I have sleepless nights. A friend once recommended I’d try taking sleeping pills. I bought a bottle, but it didn’t help at all.”