In January 2016, I wrote a saga about my attempts to learn more about the National Security Agency’s “Cryptokids Fun Book,” a website and coloring book that features cartoon characters like Crypto Cat, Decipher Dog, and their various spook animal friends, who exist to teach kids about cryptography and working at the NSA. At the time, the NSA told me that it would take at least four years for it to respond to my Freedom of Information Act request about how it got made.

In the years since, a handful of people have asked what ever came of the FOIA request—it is now five years later, after all. In something of a FOIA miracle, the NSA took “just” two years and a few months to process and return my FOIA, though it did redact lots of the things I asked for and did not include a budget for the Cryptokids series. I got a response in October 2017, but unfortunately missed it until a staffer at the Electronic Frontier Foundation emailed me this week and asked what happened to the FOIA. I checked my files and, to my surprise, saw that I had indeed gotten a response. Muckrock’s JPat Brown has also written several times about his own saga trying to procure documents related to CryptoKids; he has been able to get several documents I wasn’t able to, and I got several documents he didn’t. This story is based on documents from both FOIA requests.

Videos by VICE

The agency says that the program was paid for by the National Cryptographic Museum (which I went to in 2013 for one of my first articles for Motherboard), which it says is not technically a part of the NSA and is thus not subject to FOIA responses from the NSA.

The documents reveal that the CryptoKids were originally conceived of by the NSA’s “Corporate Communications Strategy Group,” according to an unclassified presentation that said the project was designed to be launched on November 1, 2005 in order to beef up the NSA’s “Kids” section, which was largely ignore during a 2004 website redesign. The strategy document reveals that, unfortunately, the CryptoKids are indeed “fictional.”

“In the interest of time, the redesign team focused most of its attention on the Agency’s missions and core messages, but did produce a modest Kids’ Page in conjunction with the launch,” the strategy document says of the 2004 redesign. “Since that time, the team has worked with personnel throughout the Agency to develop seven fictional characters to represent each of the Agency’s main missions and major skill communities.”

The “objectives” of the program state that the NSA hoped to “inspire future generations of code makers and codebreakers,” “provide students with information on the NSA/CSS’ educational programs and future employment opportunities,” and to “provide students with a high-tech and interesting resource for researching America’s rich cryptological heritage and learning about NSA.” The document also shows that NSA employees with children who had attended previous NSA events were the first to be introduced to the CryptoKids. Information about the CryptoKids was disseminated internally over the course of a week, with one animal introduced per day, beginning with Crypto Cat and culminating in what were likely highly-anticipated reveals of T. Top turtle and Rosetta Stone (a fox, “Rosie” for short).

The program overview also reveals that the NSA had a pretty extensive press rollout plan that included many Maryland and Washington, D.C.-based local and national publications, as well as a series of kids’ publications including Boy’s Life, Nickelodeon, J-14, Sports Illustrated for Kids, Teen People, Cosmo Girl, and Highlights. The document stated that it would provide interviews to media interviews with the (again, fictional) characters “as requested.”

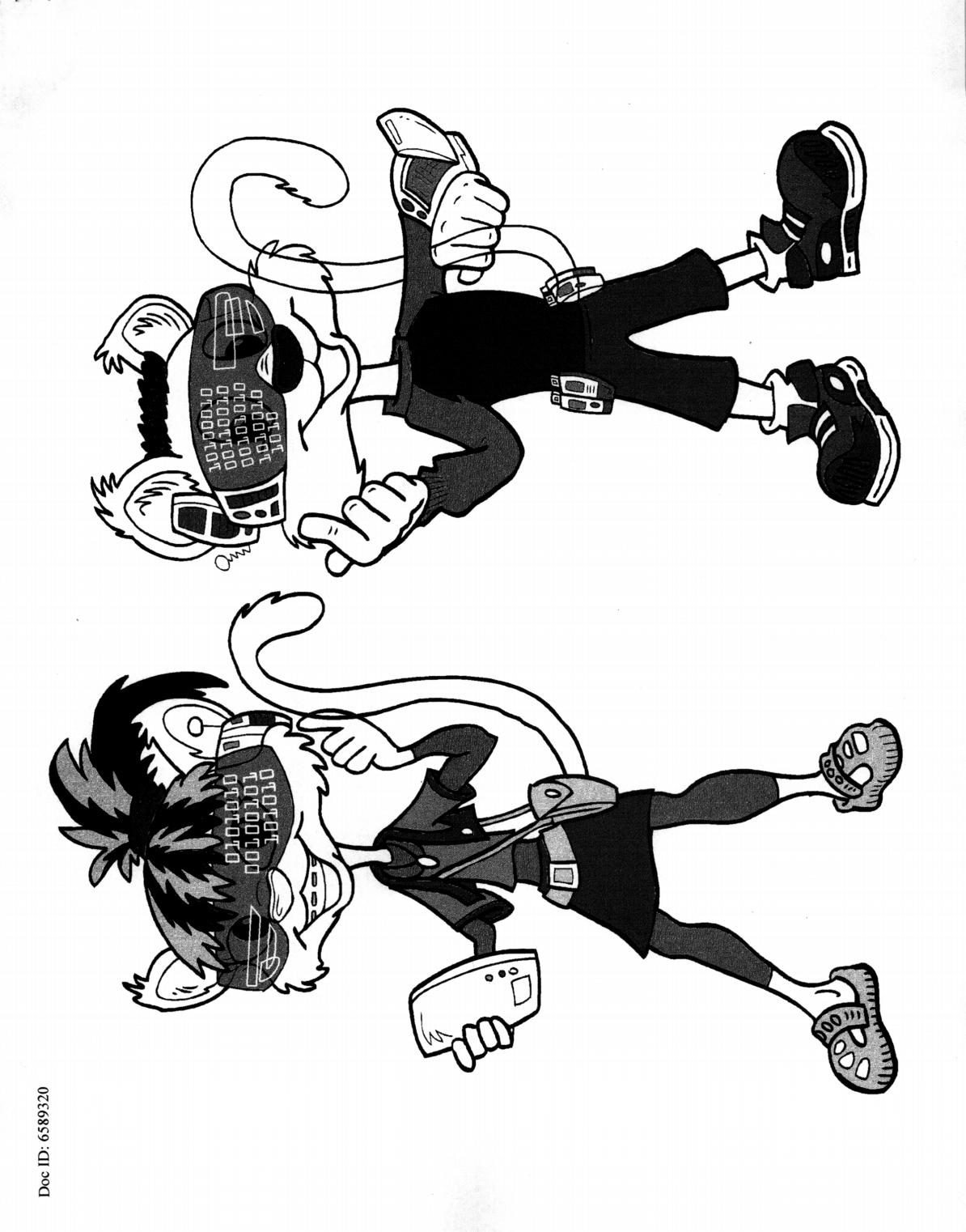

In 2010, five years after the release of the original CryptoKids release, the NSA invented some new characters, called Cy and Cindi, the “Cyber Twins,” who are cat-like creatures that the NSA claims “love everything ‘cyber.’” The documents provided by the NSA about the Cyber Twins are more specific than the creation documents for the earlier crew and show both the levels of approval were needed and some at least a little internal strife among NSA employees about What Their Deal would be.

“Both are world travelers, taking turns accompanying their Dad (a computer scientist for the U.S. Army) on his business trips around the world,” the NSA publicly proclaims. The twins’ mom, meanwhile, “is an engineer for the U.S. government.” The FOIA documents are true in a way; Cy and Cindi’s parents do indeed work for the U.S. government, but Cy and Cindi are not real. They were fabricated by the NSA’s Messaging and Public Affairs division (an office called “DN”) and were subject to various rounds of approval by public relations professionals, redacted NSA higher ups, lawyers, and classification review professionals. The person asking for permission to release these cats into the wild proclaimed in an email that a software program used to share classified information within the agency was a “stupid tool” after a failed document attachment attempt in which the cats’ coloring book pages and description were labeled “FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY.”

“In coordination for cyber security awareness month, DN has developed new Crypto Kids to go on nsa.gov,” a “corporate communications” professional within the agency wrote in a 2010 email. “Please review the bios and graphics as soon as possible.” The email claims that a redacted NSA “chief” had approved the cats’ design, and that “corp comms has also reviewed and finds it consistently with Agency messaging and approved for posting to nsa.gov.”

A classification review written in comic sans font by someone at the agency determined that the Crypto Twins had been “reviewed for classification and public dissemination” and decided that the cats had been “UNCLASSIFIED” and “APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE.” The person doing the review had estimated that the classification review process might take up to 25 days but ultimately—and perhaps hastily—made a “FINAL DETERMINATION” in less than two hours.

An NSA lawyer had some sort of problem with the level of detail in the twins’ bio, which was redacted in the documents. The flack working on the case explained in response that she was only sending through an introductory bio and that the twins would “have more in-depth back stories once we have time to develop.”

“Well, that is MUCH better!,” the lawyer responded. “Thank you! We have no other concerns.”