“Fuck. My. Hooooole!” Ben Hopkins craned their neck back for a celebratory howl. We were in Ricky’s, a sort of wonderland for cosmetics and hair care in New York, and I’d just told the band PWR BTTM that Noisey had given us $50 to buy whatever makeup we wanted. Hopkins and bandmate Liv Bruce had been eyeing the top-shelf wigs behind the register for their balding third touring member, Cameron, but as soon as I’d explained the deal, both dispersed into the aisles.

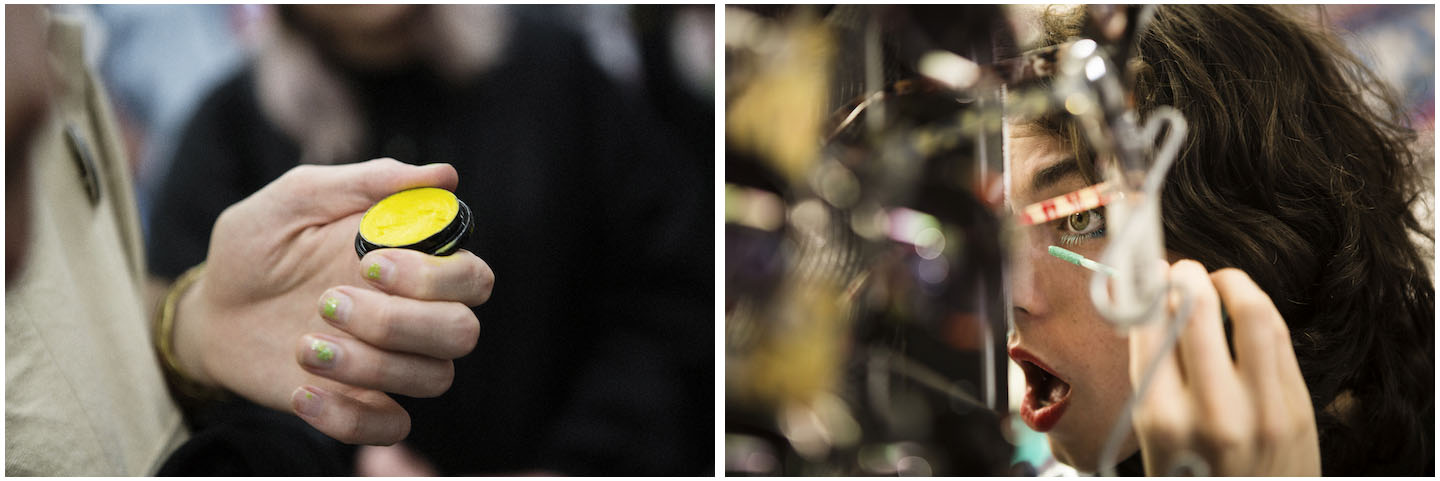

Bruce went straight for the aquamarine mascara, unscrewing one and swooping the candy color over their lashes. Hopkins, losing all chill whatsoever, headed for the face paint. I picked up a box of fake lashes, fascinated at how anyone could apply them to their eyeballs without making them look, well, fake. “I usually just plaster them to my cheek,” Hopkins said matter-of-factly, as if I should’ve been doing the same all along.

Videos by VICE

An eager cashier with a blue mustache handed over green and white tubs of paint, which Hopkins swatched on their skin. It’d do. With pastel lashes, Bruce scanned the NYX lipsticks, selecting a Barbie pink tone and holding it up to my lips. That’d do, too. In the end, we hauled two mascaras, a lipstick, two face paints and a tub of glitter to the register to check out.

All this makeup was supposed to go on my face. It was this fantastic and unoriginal interview idea I got when I heard PWR BTTM was putting out their second album Pageant (the band’s first on Polyvinyl, out May 12)—you know, to get a little color for the interview by leaning into the band’s aesthetic. Hopkins goes onstage in long, ripped polyester dresses, sweat melting makeup into their stubble. Smearing pigment across their face is a “fuck you” to beauty standards. At the band’s NPR Tiny Desk Concert in 2016, Hopkins smacked star-shaped stickers under their eyes, swiped a glitter gloss messily over their lips, strapped on swim goggles and stuffed a bouquet of fake flowers in their hair, along with a butterfly clip. I thought this might be a good idea for my PWR BTTM makeover.

But as soon as I heard the wild guitar shredding on the first song off Pageant, I realized that the point is not about makeup. It’s that PWR BTTM might just be the greatest rock band right now. And we can’t even get past their first layer.

“I’m not the first person to rub shit all over my face,” Hopkins, 25, said once we’d nestled into a table at Chelsea coffee shop La Colombe—where they had, coincidentally, once applied for a job and never heard back. “People in indie rock just don’t know about it. They don’t know about The Cockettes. They don’t know about Taylor Mac. They don’t know about Ethyl Eichelberger. They don’t know about Reza Abdoh.”

I know nothing about Reza Abdoh, just one of the theater legends that inspired Hopkins’s onstage look, and I don’t think I’m alone. For many people, PWR BTTM’s sparkly essence, regardless of its theatrical reference points, is what pulls them in. Whether or not it’s fair, PWR BTTM’s makeup is essential to getting noticed, Bruce observed, sipping on a coffee—so they plan on continuing to ride that societal standard to success. If their look is a catalyst to the music, might as well keep doing it.

“OK, so the music industry is a fucking beauty pageant,” Bruce, 24, said with the type of gusto needed for serving up strong, yet necessary, tea. Bruce, who’s transfeminine, might just include mascara and lip color before going onstage, yet their “girl next door” attire often gets pulled into the same category as Hopkins’s costumes. Their makeup gets treated like a novelty rather than normality. “If you go to any venue in America, especially a venue that shows a lot of indie rock, look at the posters, and you will see, with some exceptions, you will see pictures of young, white, attractive people.

“We live in an immensely visual culture,” Bruce added. “For that reason, I think the visual component of this band is part of what gets people to click on it at first. I know a lot of people have said, ‘I clicked on your Tiny Desk Concert because I thought, “Oh my god, what the fuck is that? I have to see it.”‘”

“That’s how I get laid too, actually,” Hopkins quipped.

Bruce finished their thought: “I like to think that’s not all that’s there.”

The consensus that rock is dead—or at the very least, it’s “the new jazz“—is quickly spreading, and indie rock is the worst offender. Every buzzy “it” band of the week is playing off of something—the Laurel Canyon singer/songwriters, the post-punk of The Fall and Joy Division, the nonchalance of 90s darlings like Pavement or whatever. But PWR BTTM is playing themselves.

“I can’t think of another band that does what we do and is who we are in our specific time and place in the music scene we grew up in,” Bruce said.

Both members of PWR BTTM hail from eastern Massachusetts, but they didn’t meet until Bruce stumbled into Hopkins’s room at Bard College, about two hours north of New York. Bruce approached Hopkins about starting a band when they heard Felix Walworth (Told Slant) was getting together a queer- and female-fronted music festival at Bard. Although the festival never happened, the duo, both self-taught musicians, stuck with the idea of the band. While Bruce finished up their dance degree, Hopkins, who had graduated from the theater program a year earlier, stuck around campus pitching PWR BTTM to record labels. After the independent imprint Father/Daughter noticed their video for “Carbs,” a song about overeating pasta and the like, PWR BTTM got signed and moved to Brooklyn the next year.

A new scene of upstate bands was sprouting from Brooklyn DIY venues like Shea Stadium, Palisades, and Silent Barn. Wielding lo-fi, bedroom indie rock, acts like Diet Cig, Jawbreaker Reunion, Frankie Cosmos, and Florist were all clumped together in a Bandcamp boom. PWR BTTM’s early music had zero gloss and a goofy garage rawness, sticking to mostly guitar and drums, with Bruce and Hopkins switching off on vocals. But with their 2015 debut LP, Ugly Cherries, which spawned the ever-so singable “I Wanna Boi” and “Dairy Queen,” they tightened their sound. PWR BTTM had the distortion and speed to set them apart from their quieter peers, and they had the in-your-face look and stage presence to match. Their live shows—of which they played more than 150 last year alone—quickly became legendary, both for their spectacle and their energy. With Hopkins’s dramatic look serving as inspiration, other queer kids have been encouraged to come out from isolation and draw attention to themselves, and fans often show up to gigs wearing just as much, if not more, glitter as Hopkins.

“We live in an immensely visual culture. For that reason, I think the visual component of this band is part of what gets people to click on it at first.”

Although some of rock’s previous saviors maybe verged on taking themselves too seriously—ahem, The Strokes—PWR BTTM are having a fucking blast, and they’re doing it while bringing you to tears and making your heart hurt. They throw parties for the introspective and use their own songs as therapy. Pageant is a massive feast of Bruce’s and Hopkins’s guts, carefully arranged as anthemic tell-offs, swampy and contemplative tear-jerkers, grungy breakup masterpieces and all-out ragers about gender, body image, confidence, love and growing up as twentysomethings who feel like they’re still teenagers.

The album rips open with a mind-melting guitar riff à la AC/DC’s “Thunderstruck.” That riff is created with a “tapping” technique, which has become a Hopkins signature along with their guitar’s open tuning, which allows the duo to sound a lot bigger than two people. Hopkins’s blistering guitar work is all over the project, and it makes me sad to think of the people in this world who are unaware of their ability to shred.

“It’s really, really hard to do at first,” Hopkins said about tapping, which has the guitarist rapidly pressing the strings on their fretboard with both hands to create a chaotic waterfall of notes. “I think I just challenged myself and that’s what I’m used to doing. And underneath that, I’m plucking the bass notes with my thumb.” Hopkins held up said thumb, which had a thick, plastic nail glued to it: Fake nails work like built-in guitar picks.

“Was I silly to love you with the force of my heart / One that’s queer and alive and so sad from the start / Silly to think that you would ever change?” Hopkins sings about an ex on the opening track, “Silly.” Later in the song, they flip the sentiment on themselves, wondering if they could ever change either. Despite all the emotional chaos going on in the lyrics, there’s a burst of empowerment in Hopkins’ reclamation of the word “silly.”

“The term ‘silly’ is a term I’ve always hated,” Hopkins said. “I was referred to as ‘silly’ for feeling effeminate, which what I now understand to be outwardly queer. I’d have people in my life subtly shading me for it. I feel pride playing it. It’s about self-satisfaction and happiness.”

Hopkins and Bruce cite R.E.M., James Taylor, and Neutral Milk Hotel as influences for the record. The latter is a big one for Hopkins—”I think that if you listen to ‘Two-Headed Boy’ or something like that, ‘Pageant’ is like that,” they said. “LOL,” a gut-wrenching ballad with possibly the best songwriting Hopkins has ever pulled off (“When you are queer, you are always 19”), climaxes with a gush of voices, cymbals and horns, which all drop out suddenly, just like the end of Neutral Milk Hotel’s “Holland 1945.”

Pageant‘s instrumentation is something new for PWR BTTM, breaking the band’s minimalist roots of just guitar and drums. Not only does it feature the vocal stylings of Hopkins and Bruce, but Kiley Lotz of Petal joins in, along with Chris Hopkins (a.k.a. Ben’s mom). “She kept saying ‘You’re the boss,’” Hopkins recalled about directing their mom, a former professional singer who wrote all her own parts and now plays shows with the band. Alex and Noah from Diet Cig are in there as well, along with whomever stopped by PWR BTTM’s recording studio upstate.

Cameron West—that’s the guy Bruce and Hopkins were going to buy a wig for—arranged all the horns on the album. Also a Bard alum and theater nut like Hopkins and Bruce, West lived in the same freshman dorm as Hopkins, and the two of them used to jam together. The idea to get West into the mix started with a lust for saxophone: “It was just kind of like a happy accident that we found someone who had the ability to arrange, and also he knew a flautist, a violinist, a cellist, a bass trombonist,” Bruce said. After West’s work arranging the instruments on Pageant, Hopkins and Bruce invited him on tour with PWR BTTM. “Who would have ever thought PWR BTTM would have a french horn player?” Hopkins said, taking a bite of some sort of vegan carrot cake. “But we do now.”

Sitting in the cafe, PWR BTTM were excited to be talking about their music. Each answer had them excitedly swapping stories about where they recorded (The Cracker Factory in Geneva, New York; Shea Stadium in Brooklyn; and their producer Christopher Daly’s house in New Paltz, New York), the philosophy behind their album cover (the dried flowers are from a lesbian wedding in Geneva), the intricacies of their guitar parts and their newfound style of singing. They watched me flip through wrinkly pages of notes to find the next question.

“Do you realize no one ever asks us these questions?” Hopkins asked. “People only ever ask us what it’s like to be queer in music, which is great, but we also make amazing records.”

“We’ve said it so many times,” Bruce added. “And, ‘How the fuck did we meet?’”

“People only ever ask us what it’s like to be queer in music, which is great, but we also make amazing records.”

Bruce sat up in their backless chair and corrected their posture. “Can we go through the track list and say where each song first exploded?” Bruce asked, spreading out their fingers to count down the album tracks.

Most of Hopkins’s songs were written in tiny, cramped spaces. “I’ve never thought about this before,” Hopkins said, musing that claustrophobia might have been the reason why they tend to write in enclosed spots. It’s their only way to control a situation they hate.

“You write in these spaces that freak you out,” Bruce said. “You should write a song in an elevator. It would be the best song ever.”

Meanwhile, Bruce’s “Answer My Text,” a song about the agony of getting ghosted, sprung from a basket of unlimited breadsticks. “We were at Olive Garden on the West Coast tour and Ben was tweeting their ass off,” Bruce said. “I was also using a weed vape pen that we got for free. I was just puffin’ on my weed vape pen outside and the chorus of ‘Answer my Text,’ like Thor’s hammer, slammed into my brain.”

“Answer My Text” is the album’s karaoke moment that has Bruce yelling brattily at the dick who won’t respond to their emojis. The melody is major-keyed, simple, and playfully sung, transporting Bruce back to the frustrating dating days of high school. “I felt so cool when we got home late / And made my parents’ furious,” Bruce sings. However, the lyrics couldn’t be more inaccurate—Bruce didn’t start dating until college. Instead, “Answer My Text” dreams up the youth they always wanted.

“I had a very lonely adolescent gay boyhood that didn’t feel right, and so that song is me living out this fantasy of like being a teenage girl because I never got to be a teenage girl,” Bruce said. “It’s a revisionist history of my teenage years.”

Unlike Hopkins’s knack for writing while shuttered in a $450 Brooklyn bedroom, Bruce’s songs bloom from movement. You can hear their gait in “Kids’ Table,” a moderately paced ditty that sprouted from a walk down the street. “I’m starting to move more like a fish in the sea than a train on a track,” Bruce sings. “Glued to my seat at the kids’ table / I’m learning to walk with a chair on my back.” The song shows the first droplet of maturity in the album, the first half of which is doused in insecurities and the feeling of being young and incompetent.

From “Answer My Text,” where Bruce claims “my teenage angst will be with me well into my 30s,” “Kids’ Table” finally has them moving toward adulthood. And sometimes adulthood means self-care, like eating a proper meal or going to a laser hair removal appointment. (“Went to a room where a woman with ‘Joy’ in her name shot my face with a light / A light so intense and specific it burned up the hairs and they fell out tonight.”)

“[Laser treatment] is something that I secretly wanted for years but finally allowed myself to do and increased my quality of life astronomically, due to gender dysphoria,” Bruce said with a sly grin. “That was great. I don’t feel that way every day ever since I wrote the song. Some days I feel like [I do in ‘Kids’ Table’]. Some days I do forget to eat dinner. And then other days are better.”

It’s a vicious cycle. Sometimes PWR BTTM is drenched in a feeling of inadequacy. And sometimes they’re confident as hell. In “Wash” and “Won’t,” Hopkins wades in the aftermath of a doomed relationship, questioning everything—mostly themselves. On “Now Now,” they open with the line, “I’m gonna beat myself up for beating myself up.”

“I was feeling really down,” Hopkins said about writing the song. “Like, ‘God, I feel like shit. Oh, I’m so shitty for feeling like shit. Why do I feel like shit? That’s so shitty.’ So the song turns into this totally insane, oh, well if you’re going to beat yourself up then I’m going to kick myself to the moon and write a strongly worded email—all this weird, stupid shit.” But on “Big Beautiful Day,” a more aspirational song, they know exactly who they are, and they’re plowing down everyone who gets in their way. This version of Pageant is loaded with fuck-you lines aimed at haters, usually delivered ferociously, like, “My advice is to look incredible / As you make their lives regrettable / By being your damn self.”

You can imagine PWR BTTM telling off boneheads on the street with each line, and you can see them chewing out haters or assholes who can’t be respectful. But Bruce explained that most of the stuff they write is wishful thinking. At the end of “Sissy,” they fire out a spoken-word rap about a catcaller heckling them while they’re walking home from a bar in a dress. “I’m beautiful and you can’t take it / I’m heavenly and you can’t deal! / Roll your window up and keep on driving / HIT ME UP WHEN YOU KNOW HOW TO FEEL.” The song ends in a crash of cymbals punctuating each word like clap emojis. I imagine the catcaller whimpering and driving off to rethink his life.

Bruce told me that “Sissy” was the comeback that never happened. “I aspire to be more like ‘Sissy’ than anything,” Bruce said. “That interaction where I tell off the person in the passing car, that didn’t happen. That person drove away. And I didn’t say anything. And then I wrote that. Like, this is what I should’ve done. This is what I’ll do next time.”

How do you change? Can you change? Most importantly, what little things can you do for yourself to live with the fact that maybe things won’t change?

While some of the songs detail heartbreak and some of them are about gender dysphoria, there’s one constant theme on Pageant: change. How do you change? Can you change? How do you convince yourself you can change? How do you convince others to change? Most importantly, what little things can you do for yourself to live with the fact that maybe things won’t change?

That change might be reaching out to haters who can’t understand (“Jesus Christ, let’s help them!” Hopkins sings exasperatedly on “Big Beautiful Day”) or, for Bruce, that change means hormone therapy. The last song, “Styrofoam,” explains Bruce’s discomfort in their own body and was written just as they had started estrogen. In the few months before Bruce saw any of the effects of the treatment, they wrote these lyrics: “I wake up and my body is my body / It looks like candy and it feels like Styrofoam / And if I could, I’d take it off / And take a walk around the block / But since I’m stuck here, I guess I’ll make it home.” Bruce shouts the last “home” into the ether, and then repeats it three more times with plenty of reverb, as if trying to convince themselves that they’ll be safe inside their body for a little bit longer.

“At this time last year, although I didn’t identify as male, I had a young, white, thin, toned, able-bodied male body which is what our society deems attractive. But it didn’t feel good,” Bruce said. “But I knew I was doing something about it and that was really exciting. It was like a two-month long night before Christmas.”

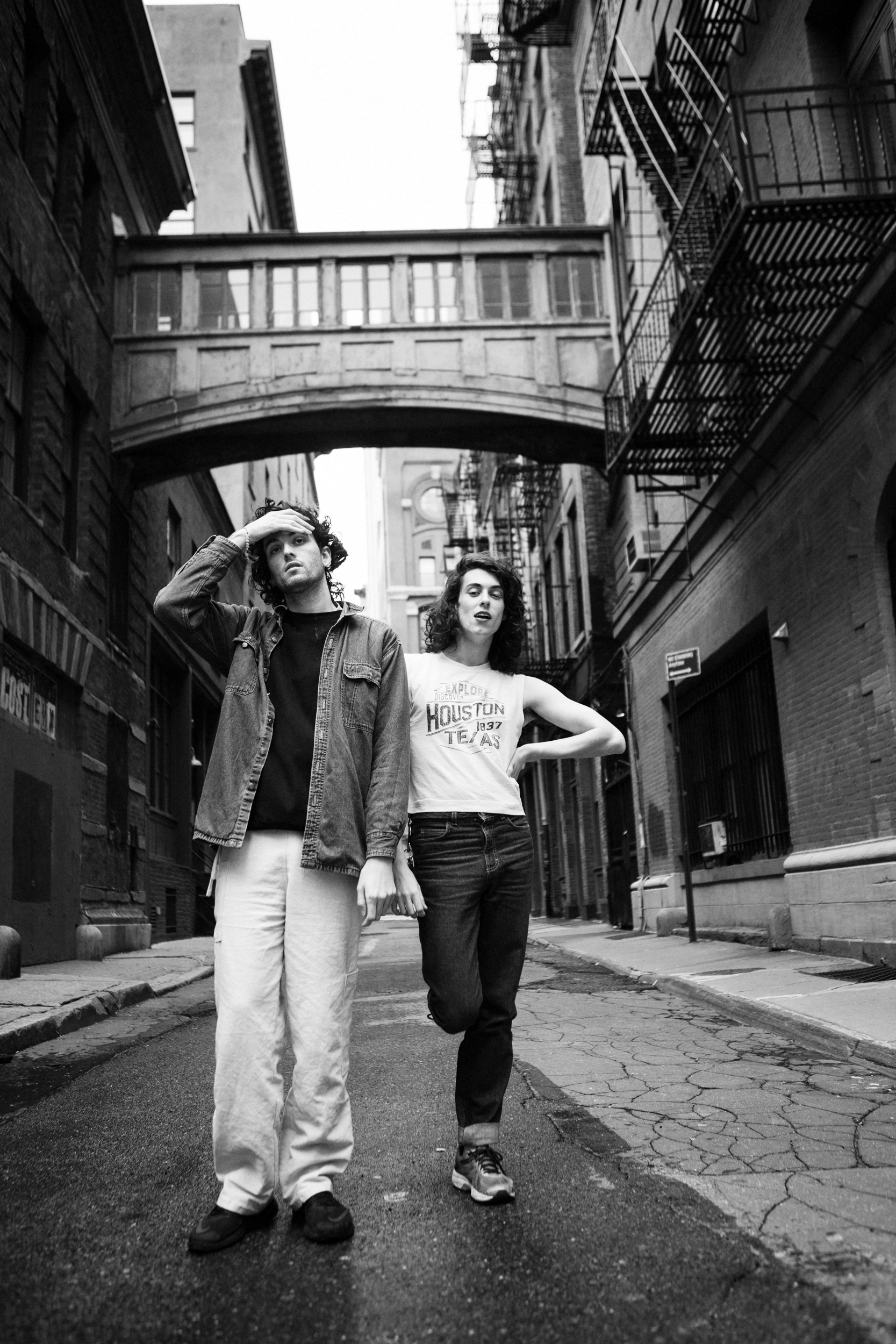

We finished with caffeine at La Colombe and walked out into the Tribeca street. It was time to finally put on some of the makeup we bought. Because of our conversation, we wondered if we should skip the makeup portion altogether and just do a photoshoot (“We love being on camera,” Bruce said). But selfishly, I kind of wanted to try that aquamarine mascara Bruce put on at Ricky’s. They made a plan: Liv would do one side of my face and Ben would do the other—each in their own style.

Bruce, detailed and methodical, lined my bottom eyelid with a bright blue pencil from their own personal stash. They had me apply the pink matte lipstick myself, to only the left side of my lips. I looked like one of those beauty YouTubers showing off *the power of makeup*.

Then it was Hopkins’s turn. They took the lipstick from me and smeared it all over my mouth, letting the pink overline my lips like I was a drunk Kylie Jenner (or sober Miranda Sings). The lipstick made its way down to my chin. I felt fierce. Hopkins continued, gobbing forest green and white paint right down my frown line, unfortunately accentuating my jowls. For a finishing touch, they loaded up the palm of their hand with gold glitter and started slapping my face. It kind of hurt, but I’d heard somewhere that pain is beauty. I held my phone up on selfie mode to see the final product. I liked it. Each side of my face told its own story. It was a little bit of Ben, a little bit of Liv—a little bit focused, a little bit messy. Careless and confused, yet careful and poised.

Jessica Lehrman is a photographer based in New York. Follow her on Instagram.

Emilee Lindner is a writer based in New York. Follow her on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

Casper -

-

Photo by Ethan Miller/Getty Images -

AEW