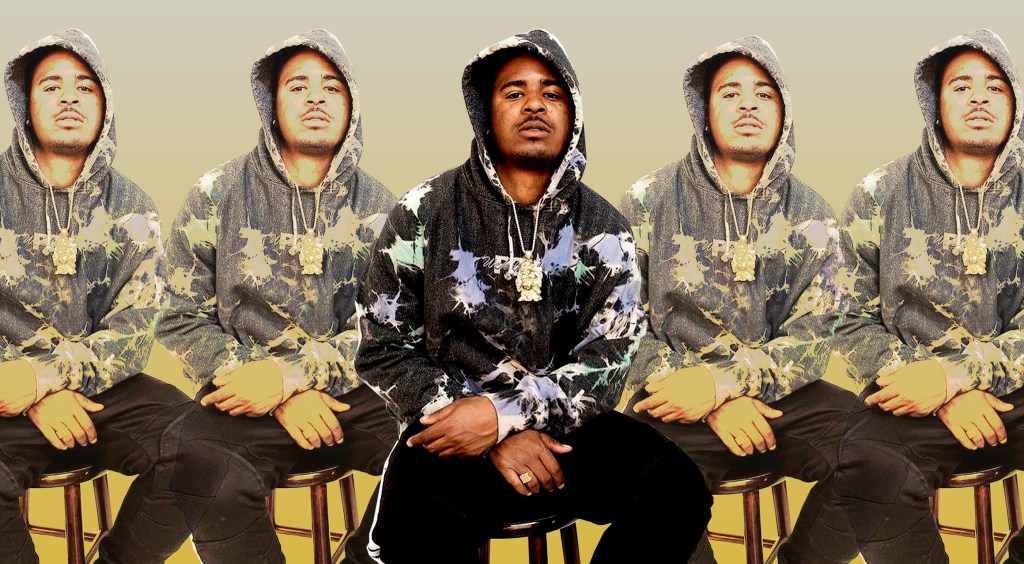

A group of New York City Lite Feet dancers trades moves and tricks at a “lab session” in mid-February. Photo by the author

It was below freezing and spitting sleet, but the men gathered in the back room of the community center in Brooklyn’s Atlantic Terminal public housing project were sweating bullets. Malcolm Fraser peeled his T-shirt up around his ribs, gripping the hem in his teeth to cool his body. It was early February, and in a few weeks he would be headed to Shanghai to teach Chinese hipsters how to dance like he does, so the moves had to be perfect.

To most people, this might sound like the establishing shot of a lucrative Hollywood film franchise. To the New York City Police Department, it’s a possible criminal conspiracy.

Videos by VICE

Fraser is nobody’s idea of a gangster. At 20, he retains the lightswitch smile and megawatt energy of a grade schooler, and when he hasn’t got shoes or hats or shirts in his mouth, he’s a passionate and convincing evangelist for a style called Lite Feet that is popular among—though far from exclusive to—performers who dance in the New York City subway.

Dancing on the train is illegal—Fraser knows that as well as anybody. Over the past nine months, the NYPD has redoubled its efforts to drive performers from the system, and the MTA has piled on with an anti-dancing PR campaign.

What’s less visible and more alarming to young men like Fraser is what appears to be a police policy that lumps dance teams in with violent street gangs, effectively criminalizing the activity.

“Todays kids are very acrobatic, they’re good dancers, and they go out there and compete in competitions and form these crews,” NYPD gangs expert Sergeant Dwayne Palmer told the crowd at the 115th Precinct in Corona, Queens, during a December presentation on the hundreds of loosely affiliated youth groups.

The audience listened as Palmer described how teams of performers exact bloody revenge on one another for pride wounded in dance battles, and known gangsters raise cash for their criminal exploits doing backflips on the morning commute.

“We saw [notoriously violent Brownsville rivals] the Hoodstarz and the Wave gang, they would go out and compete for money,” Palmer told the crowd.

That claim made Fraser laugh out loud, as in actually double up on himself in a genuine burst of childish giggling.

“Are you serious?” the Brownsville native cried when I related the expert’s comments to him, his tone incredulous. “I grew up with all of them, like literally, I know every single one of [the gangsters] that’s arrested or that’s there. We were PS [Public School] 165, PS 183, it’s like those two schools.” He shook his head in disbelief. “These guys, they’re not dancers!”

In fact, many of the Wave Gang and the Hoodstarz are behind bars, swept up in the same style of conspiracy prosecutions that put away members of the Gambino family and the Trinitarios in years past. Starting in the early part of the decade, the NYPD began a dramatic overhaul of its gang policy, shifting attention from brand-name organizations like the Bloods and the Crips to smaller, younger, and more casually associated groups like the Bad Barbies and the Brower Boys.

Between 2012 and 2013, city law enforcement indicted more than 400 people—most of them, like the 43 alleged members of the Hoodstarz and Wave gang, between the ages of 13 and 21—for crew-related crimes, and the number of neighborhood cliques with clever names being monitored as violent criminal conspiracies climbed into the hundreds.

“It’s total madness,” said Dr. David Brotherton, a gangs expert and chair of the sociology department at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York. The cops “don’t have any definition [for crews]—they make it up as they go along. The definitions they use are simply definitions that are self-serving.”

Those definitions are also exponentially more elastic than they once were. Mafia families were called that for a reason: Outside of blood kin, entry was extremely limited. The prison-born gangs of the 80s and 90s warred over colors and exacted lifetime membership through brutal initiation rites. By contrast, the ranks of modern NYC crews come and go as they please. What ties them together in court can be as ephemeral as YouTube videos and hashtags.

“They’re not using the word gang, they’re using the words like team, family, set,” Palmer explained. “With this new structure that the kids have decided, I can be a Blood, I can be a Crip, but I don’t have to identify with that organization. We can say we’re Northern Street Boys. We [the NYPD] call that crew gangs. The thing that’s important for us to know is that once a crew commits a criminal acts—all crews once they commit a criminal act—they’re considered a gang.”

The trouble is, without tattoos, colors, or even set names, defining who is and isn’t a part of a group committing crimes is murkier than ever before.

“There’s no public agency that [the police] have to go to and say, ‘We’re about to engage in this practice where we’re monitoring the behavior of groups of dancers because we think they’re related to the criminal activity of gangs,’” said Robert Gangi, who heads the Police Reform Organizing Project (PROP), a law enforcement watchdog in Manhattan. “If they had to, there might be some instances of somebody saying, ‘What the fuck are you talking about?’”

If the definitions of criminal conspiracy expand to cover more and more young people, the punishments remain fixed: a conspiracy charge automatically ups the mandatory sentencing minimum on other offenses. Increasingly, and especially in the case of youth crews, the tapestry of such charges are woven out of online correspondences.

“I’ve been arrested before by police, I have friends who’ve been arrested before by police, and they’ll ask you, ‘Oh, you’re in the [Facebook group] Lite Feet Nation chat?’” explained performer Elijah Soto, who teaches dance through the Lite Feet group Mindlezz Thoughtz. “They watch us from Facebook. I’ve seen my friends, their profile pictures in the police station. I’ve seen my own comments on Facebook written in printed paper.”

Fraser recalled an equally chilling tale from the one and only time he was arrested, after dancing on the train a few weeks back.

“They asked me when I was in the cell, ‘Oh, are you down with Lyve Tyme?’” he said. “I was like, ‘What does that have to do with anything, what’s going on?’ They were like, ‘Oh, we just wanted to know.’ I was like, ‘That’s a dance team, it doesn’t matter, even if I was down with it, it’s not a gang that you could indict me for.’”

It’s unclear whether the NYPD currently considers Lyve Tyme, Lite Feet Nation, or any other specific dance group a criminal crew; the department did not return calls or emails for comment on this story. But if, as Palmer’s lecture suggests, the department is beginning to label them that way, dancers could presumably be indicted just like gang members, simply for their association.

“You go away for a long time,” Brotherton said of young people charged in crew conspiracies. “It’s really very serious—once you start throwing that around, the defendant often cops a plea very quickly. He knows he faces some pretty dire consequences if they go to trial.”

There is a streak of the absurd in all of this: A decade before most Lite Feeters and their dancing brethren were born, DARE instructors were already dreaming them up as the bright alternate futures for would-be drug dealers. Even today, gang prevention is largely structured around youth engagement, much of it funded by law enforcement in the form of group activities like sports and arts programs. At their most fundamental level, shoe tricks and ankle formats turn idle time into positive energy, whether on the train or in the park or at home in front of an iPhone.

“Dancing on the train is the smallest part of any dancer’s day. They dance and go get something to eat and then they go battle or they cypher or they do stuff like this,” Fraser told me, straining to be heard over the noise of a late Sunday night lab session—slang for practice—in mid February. “No killer you know is doing that. I’m sorry, you could be the most cold-hearted person, [but] after you kill somebody, you’re not gonna feel like dancing.”

Gangi, the police reform advocate, agreed: If what were happening to Fraser and his friends weren’t so terrifying, it’d almost be funny.

“That’s painfully ironic, that China of all places—what we think of as an autocratic-at-best country with little freedom artistic or otherwise—they’re inviting this young man to teach them his skills and give them the benefit of his creative inspiration, and in New York City we criminalize him for it,” Gangi told me. “It’s deeply fucked up.”

Follow Sonja Sharp on Twitter.