A federal judge in Cleveland, Ohio, has ruled against a university’s use of controversial anti-cheating software which required students to capture images of their private rooms before taking remote exams.

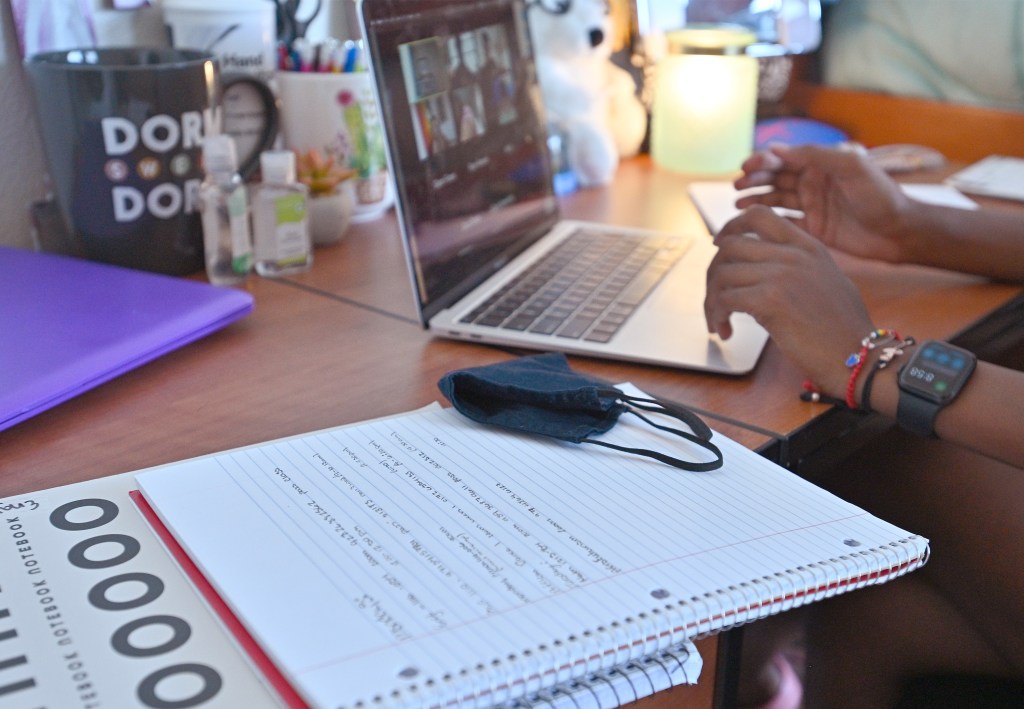

The lawsuit was brought by Aaron Ogletree, a chemistry student at Cleveland State University who argued that the software violated students’ privacy by asking them to scan their rooms before tests. The room-scanning feature became a fixture during the early parts of the COVID-19 pandemic, when classes moved online and schools and universities sought ways to monitor students using technology that claims to prevent cheating.

Videos by VICE

But like many other students who have criticized the proctoring software, Ogletree objected to the virtual intrusion, and sued the school, which is a public institution, for what he claimed were violations of his Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable search.

In a decision released on Monday, a federal court agreed.

“Though schools may routinely employ remote technology to peer into houses without objection from some, most, or nearly all students, it does not follow that others might not object to the virtual intrusion into their homes or that the routine use of a practice such as room scans does not violate a privacy interest that society recognizes as reasonable, both

factually and legally,” Judge J. Phillip Calabrese wrote in the ruling for Ohio’s Northern District. “Therefore, the Court determines that Mr. Ogletree’s subjective expectation of privacy at issue is one that society views as reasonable and that lies at the core of the Fourth Amendment’s protections against governmental intrusion.”

Motherboard has reported extensively on proctoring software like Proctorio, Respondus, and Honorlock, which became widely used for remote test-taking during the pandemic. The companies behind the software claim it stops cheating using a variety of often-unsettling methods, like tracking students’ head and eye movements and sending instructors alerts for “suspicious behavior.” But students, parents, and school administrators have expressed a laundry list of complaints about the software—that it doesn’t work, uses racist algorithms to detect faces, and negatively impacts disabled and neuroatypical students.

Proctorio in particular has also been extremely litigious in response to the criticism. The company has sued critics for posting publicly available information about how its software works, and sent subpoenas demanding information from digital rights groups that spoke out against the software. Proctorio was not a part of Ogletree’s suit; Respondus and Honorlock were the companies used by Cleveland State that were relevant in the lawsuit.

Ogletree’s lawsuit notes that while Cleveland State technically doesn’t require students to use the room-scanning feature, the software’s step-by-step instructions guide users to use it anyway—meaning many students likely did scans thinking it was mandatory. Cleveland State University also tried to argue that the room scans were justified because they are routine and preserve academic integrity for remote exams. But the court disagreed on both counts, pointing out that the scans don’t prevent cheating in practice and arguing that Ogletree still had an expectation of privacy in his own home, even if this type of software had become standard.

“Based on consideration of these factors, individually and collectively, the Court concludes that Mr. Ogletree’s privacy interest in his home outweighs Cleveland State’s interests in scanning his room,” the judge concluded. “Accordingly, the Court determines that Cleveland State’s practice of conducting room scans is unreasonable under the Fourth Amendment.”