It’s 11:30 PM on New Year’s Eve and I’m kissing a boy when the lights go on. My first thought is that someone is snapping a photo of us, and I turn my head to fire off a cunty, “girl, stop.” But it isn’t a friend or photographer I see, but ten members of the NYPD walking through the doors of a Crown Heights DIY art space where my New Year’s Eve party, Night Riders—conceptualized as “Westworld meets Joanne meets Studio 54” —is just starting.

The next few hours seem almost surreal: the cops ask for our liquor license, which, of course, we don’t have. “Party’s over,” they tell the small crowd who had come for our free champagne toast at midnight. The police are not interested in talking to us, the promoters. They just keep asking to speak with the owner of the space, who isn’t there, so they focus on the security guard, an elderly man of color. We take down our lights, pack up the CDJs, unplug the fog machine, rip down streamers, and climb up ladders to pack up projectors we’d only finished installing two hours ago.

Videos by VICE

Queer people are not given the opportunity to profit within the system, and then are punished for attempting to support themselves outside of it.

In my four years of experience as co-director of The Culture Whore, throwing over 50 immersive queer events mostly in DIY spaces, this is a scenario that only existed in my worst nightmares. Cops have shown up at almost all of our parties and even walked inside, but always just to check in, with the attitude of parents making sure their kids were being well behaved. They have never actually shut us down before. The energy is entirely different now: daddy’s home, the jig is up, put away your toys and go to bed. I’m not prepared to watch the cops pack away our booze and count out the cash they’ve taken from us. I’m too terrified to ask if we would eventually get the money back.

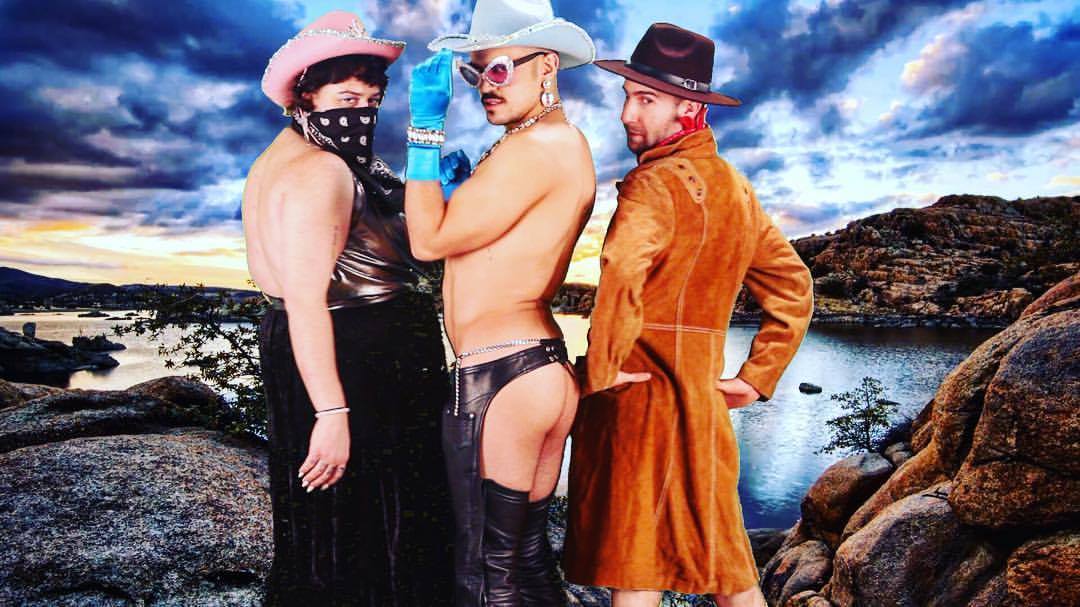

A promo photo for Night Riders with The Culture Whore’s Rose Dommu, Paul Leopold, and Rify Royalty (Photo by Ben Boyles)

When midnight hits, they wish each other happy new year. I duck backstage for a short angry cry, then passive aggressively dump ten confetti cannons into the trash. I almost scream when the officers take the cannons out of the trash and put them in their squad cars.

Two and a half hours after our party was shut down, cops from the same precinct busted a party across the street, which was taking place at the home of my good friends, known to some as Casa Diva. Charlene Incarnate, a trans performance artist and one of the residents, described the nightmare in a Facebook post in the days following:

“I’m devastated and haunted by the scene; my house full of hookers trannies and queers of color all feeling safe included and having a fucking blast, the fucking boys in blue tearing it all down just because they could, and triggering everyone who was enjoying the other-worldly haven we had created. The other night was a clear and calculated attack on queer DIY parties in the wake of Ghost Ship. It was like a gay titanic and [I] can’t get over it.”

[NYE] was a clear and calculated attack on queer DIY parties in the wake of Ghost Ship. It was like a gay titanic and I can’t get over it.—Charlene Incarnate

All week, I’ve been stuck with a feeling of violation. For queer people, nightlife spaces are crucial to our ability to organize as a community, to process our pain, to connect with pleasure, and to escape from reality. Following the tragedy at Pulse last summer, we mourned the 49 lost lives because we understood the power of clubs as holy places where we cared for each other as we carried. Safety is an illusion for queer people, and the idea of “safe space” is too. We think of safety as more than fire codes and the number of security guards in a club. Safety for us is also about being able to be in a space where we won’t be insulted and assaulted. And these dancefloors are as close as we come to that ideal.

Guests at a Culture Whore party (Photo by Santiago Felipe)

Night Riders was The Culture Whore’s final party, as my partner and I had decided focus on art outside nightlife. It was going to be a bittersweet goodbye: one last night with the people we love, coming together under flashing strobes to dance out the last few moments of a shitty year and look forward to something better. But that moment of celebration was taken away from us by a system that wants to punish anyone trying to support themselves outside of the government-sanctioned system.

“Throw your party in a club next time,” the officers told my friends at Casa Diva, as if it were that easy. There’s a reason why underground queer parties often don’t happen in nightclubs and established, legal spaces. Clubs aren’t necessarily safe spaces for queer people, even if a queer producer is running them, because we’re not in charge of the staff or security that gets hired, and often can’t be discerning about who gets let in—or kicked out. And big clubs looking to throw profitable parties are likely to reach out to established promoters, and unfortunately, there aren’t very many trans or POC promoters who are prominent enough to get those opportunities.

DIY spaces will not be able to live up to what officials deem acceptable, because the way the city’s laws are structured make it prohibitively expensive for promoters to make a party “up to code.” Liquor licenses are also out of the realm of possibility for promoters like us, because we simply don’t have the resources to secure them. This creates a vicious cycle where queer people are not being given the opportunity to profit within the system, and then are punished for the ways they attempt to support themselves outside of it.

The Culture Whore and their hosts (Photo by M. Sharkey Studio)

Over the past couple years, the New York underground DIY scene has grown tremendously, and our parties are now written about in major media publications. But all of this public attention also makes us more exposed and vulnerable to the authorities. It’s a catch-22: you want these events to be profitable, but they’re no longer underground when the cops can follow your mailing list and find out where your parties are.

Some people will point fingers at Facebook organizing as the issue, and us choosing to publish the address of the party online certainly has a role to play in the shutdown. But that’s missing the point. We had been throwing parties the same way, in the same space, for over two years. The New Year’s shutdown was not about some cocky producers getting stupid and slipping up. It was a pointed post-Oakland attack by the authorities on DIY nightlife—which is also an attack on spaces that are sacred to queer, marginalized communities.

I’m starting to think that in order for the underground to survive, it needs to go deeper underground. Maybe that means going offline, and back to handing out flyers and depending on word of mouth to promote parties. Maybe that means we stop throwing parties for profit, stop treating nightlife as a viable source of income, and just hang out with our friends when we can.

Or maybe the solution is to give queer people the resources they need to work within the system. When people ask me for refunds from the party, I’m telling them to call their local representative, and ask for more public funding for community arts spaces. Whether the underground chooses to go back in the closet or not, the current situation cannot hold, and queer nightlife needs to fight to stay alive.

Follow Rose Dommu on Twitter