Employees at a number of US cities spent hours of unremunerated time helping Domino’s make its latest ad campaign, Paving for Pizza, internal documents show.

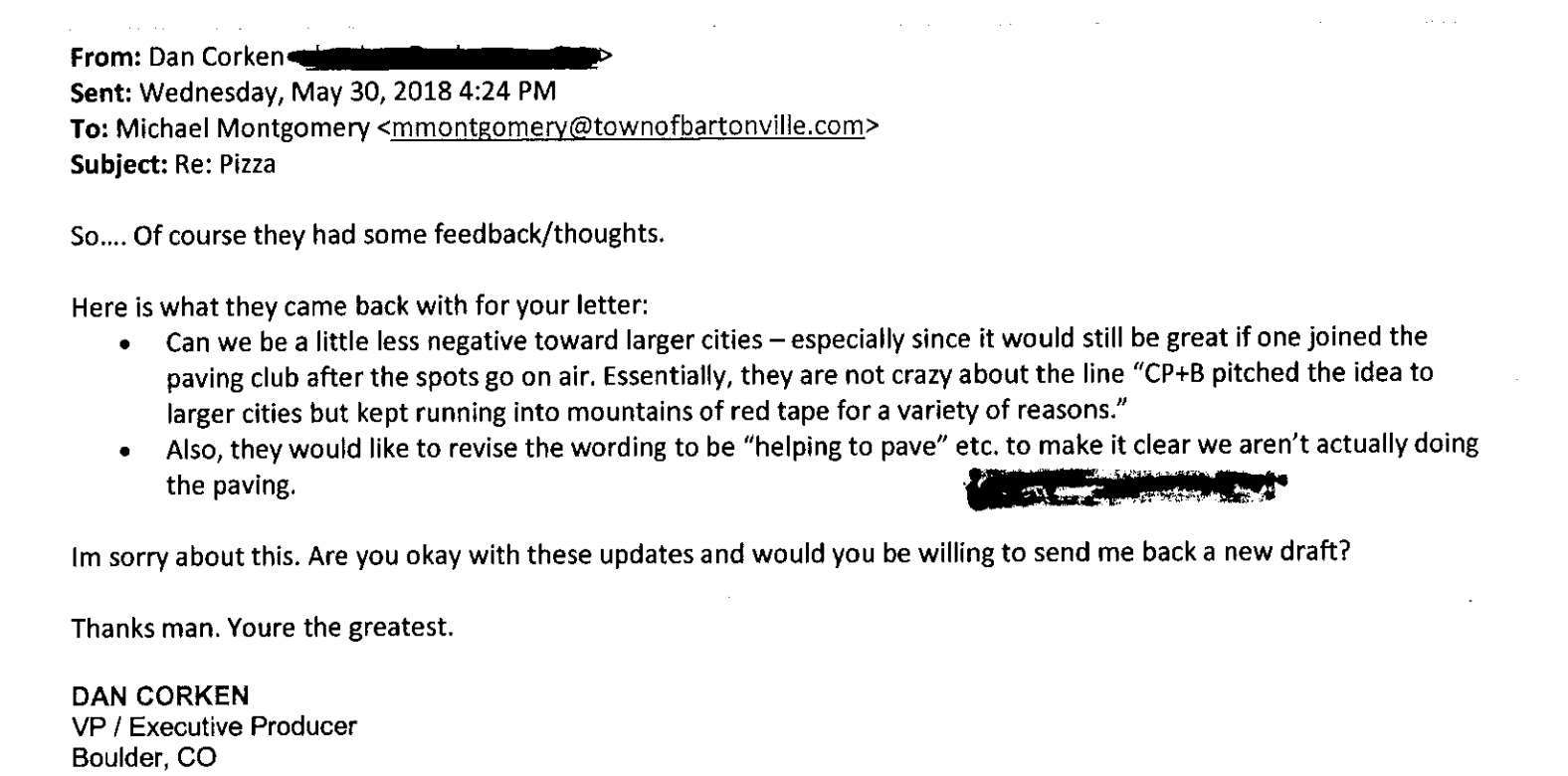

The documents, which Motherboard obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests, contain a number of long email chains that spell out the terms of the Paving for Pizza campaign, which publicly debuted online June 11.

Videos by VICE

It began as—and arguably, remains—a lighthearted gesture. The idea for the campaign came from Domino’s longtime agency of record, Crispin Porter + Bogusky (CP+B), which also made the company’s 2009 “Domino’s Pizza Turnaround” ad in which executives admit their former recipes were terrible.

The campaign’s premise was whimsical, yet simple: pothole-ridden roads damage your take-home pizza. Solution? Fix the roads and get your supper home safely.

In January, CP+B approached the cities of Athens, Georgia; Bartonville, Texas; and Milford, Delaware, offering them each grants of $5,000 to help them repair potholes in their town. In exchange, cities would carry out the repairs, take photos or videos of the repaired potholes, and stencil on a Domino’s logo along with the tagline “Oh yes we did.”

A fourth city—Burbank, California—got five potholes repaired in the filming of the Domino’s Paving for Pizza TV ad. The work there was done by the crew hired by the commercial’s production company, and not the city’s crews. The city did not receive $5,000. “We are not a partner with Domino’s,” Burbank media relations officer Jonathan Jones told me on the phone.

The company has since approached another 17 yet-to-be-revealed cities to do the same. The municipalities were chosen from nominations made on the Paving for Pizza site. No one at CP+B or Domino’s would tell me about the campaign’s total budget.

Still, the tone in the hundreds of emails sent between CP+B and the municipalities was friendly. The towns were pleasantly surprised by the offer and grateful for the cash; as Milford city manager Eric Norenberg explained in a Washington Post op-ed, his town’s budget for road repairs only amounts to $30,000 annually, and that the grant really made a difference.

Milford patched 40 potholes with its $5,000—and held a staff pizza party with the $200 in gift cards it received from Domino’s. Athens fixed 150 potholes and Bartonville did eight.

After Domino’s launched Paving for Pizza, Bartonville town administrator Michael Montgomery reached out to Norenberg saying, “Projects like these are few and far between so was nice to have a little fun with it.”

Yet, each town’s leaders and support staff spent considerable time and resources—paid for by taxpayers—replying to emails and having phone meetings, filling out contracts, and taking pictures of the patched potholes. Each of the towns also fielded many media requests, which also ate up their time. Norenberg spent hours coordinating and writing a Washington Post op-ed. According to the FOIA documents, the only money towns received for all these efforts was the $5,000 grant destined for road repairs.

Meanwhile, CP+B told the town of Bartonville in an email that by June 13—two days after it launched—the campaign had garnered 100,000 site visits, 31,000 zip code registrations from all 50 states, 700 media stories, 100,000 Twitter mentions, and landed in the number-one spot on Reddit. The launch ad has so far been viewed on YouTube 88,000 times.

This is the kind of earned media that corporations dream of. For a mere $20,000, Domino’s got worldwide exposure by surreptitiously using city administrators as puppets to advocate for the brand.

When it launches the next (and last) 17 cities over the summer and fall, it will have given towns a total of $100,000 on pothole repairs—but it will have gained a priceless amount of in-kind advertising. For reference’s sake, Domino’s ad spend in 2016 totalled $353 million, according to Adweek.

Milford’s 2018 town budget is $43 million.

The campaign has rubbed some people the wrong way. In an email to Norenberg, one concerned citizen in Delaware asked, “How will Dominoes (sic) be treated next time Planning has to revise an ordinance for their next Pizza location?” He also asked whether the city would ever allow Pepsi or Coke to control the town’s water supply.

Cities have for years contracted out road repair, snow removal, electricity plants, and other civic services to private companies. That said, it is unusual for a secondary company to sponsor road repair for the purposes of advertising. But hey—at least they got a pizza party out of it.