The elephant is Ralph Steadman’s favourite animal. Now on the red list of endangered species, elephant populations have declined by 71 percent since the artist – one of our very greatest – was born 81 years ago. It’s partly because of elephants that Steadman, Hunter S Thompson’s collaborator-in-chief of three-and-a-half decades, finally found a reason to draw – really draw – again. It’s been 12 years since Thompson was found dead at home with a bullet in his skull.

Ceri Levy used to work as a documentary maker for the pop bands Blur and Gorillaz, but felt something was missing from his life and, on a whim, became the brave and passionate type of conservationist who gets beaten up or arrested for protesting against the illegal shooting of Marsh Harriers.

Videos by VICE

Levy’s arty side made him want to lift conservation work out of the domain of angry recrimination. He worshipped Ralph Steadman and sent him a letter asking him whether he’d consider collaborating on a book (as a teenager, Levy had read Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and cribbed the drawings to pass his art O level). Steadman emailed back, saying that though he didn’t really know what Levy was on about, the project intrigued him: “I think weird is so much more interesting,” he wrote.

The two collaborators are outside Steadman’s large Georgian home, sitting on a bench in the 24 degree summer heat, amusing themselves with a never-ending string of absurd jokes. Levy is, at times, almost crying with laughter. Steadman, slightly more reserved, wears a blue amulet around his neck, bought from a Navaho Indian in Santa Fe: “14 dollars. Hunter gave me that. ‘It will ward off evil spirits.’” He looks about 65.

Because he made his career in the United States, many people wrongly assume Steadman is American. Actually, he’s from North Wales – the son of a shop assistant and a travelling salesman – and lives in the green heart of Kent, where we’re eating a lunch of bread, salad, pate and cheese. The Steadman garden rolls out in front of us; before it, a glittering swimming pool.

“Have you met Anna?” says Steadman. “Anna cuts the grass.” Anna, a teacher, now retired, is Steadman’s wife – relaxed, like her husband, amused, enjoying the heat and a glass of wine. Also here is Sadie, the couple’s daughter, and Ralph’s manager. She’s happy that her father has found another meaningful collaboration: “You get a bit introspective otherwise, don’t you, dad?” Critical Critters will be the third in a series of magnificent, illustrated books about endangered animals: Levy does words; Ralph does illustrations.

WATCH: A Gourmet Weed Dinner at Hunter S Thompson’s House

Given the subject of our meeting – the complete destruction by mankind of planet earth – this should be a sombre occasion. In fact, it’s the opposite of depressing. The two men bounce off each other in cheerful repartee. “Ralph, is that an erection you drew on the Orangutan?” asks Levy, and, later: “The baby Dratsab is one of our made up animals – Dratsab is bastard spelled backwards.”

“You can say something wise in a funny way with art,” says Steadman. “Wittgenstein said the only thing of value is the thing you can’t say.”

What’s Levy’s favourite animal? “All living things,” he says, with great feeling. “When you look into an eye of a wild creature you can see a substance in there. You might even see a soul, I don’t know.”

Steadman went to grammar school on a scholarship, disliked it, made up for it by drawing the teachers, then worked in a Woolworths stockroom before, variously, going to technical college, being conscripted, studying aircraft engineering and having a light bulb moment when he saw an advertisement that said: “You Too Can Learn To Draw And Earn £££s.” The Manchester Chronicle published his first cartoon, in 1956, but by the 1960s he was being sacked by the editor of The Times, William Rees Mogg – the amusing viciousness of his early work being thought “too seditious”. The images he’s most famous for are jaggedy, ink-splattered, savage indictments – he’s a genius of comic grotesque – and the ones he made to go with Thompson’s collected articles on Richard Nixon’s 1972 presidential campaign were considered sensationally shocking and new.

“That’s the problem,” says Steadman, smiling mildly. “People expect you to be very angry. I say, if there’s any anger, it goes down on paper. Get it out. Exorcise.” He says he wanted to do real damage to Nixon with those drawings, and yet, “I prefer Nixon to someone like Trump, who is not really political; he’s just a thug. Trumpelstistikin.” What would he do if he couldn’t make art? “Metal opera,” he says, and starts to belt out a tune he’s made up on the spot: ” I want to sing in opera / I’ve got a lovely voice / I want to sing in opera / I haven’t got a choice!“

The artful, splattered scrawl has evolved. Steadman’s favourite animal appears in Critical Critters, a shy smile on its face. “What you’re seeing here is my dirty water technique,” he explains. “I had a dreadful accident that I think was quite interesting, when I spilled dirty water from my paint brushes. It took four days to dry…” Over Skype, he showed Levy the interesting watery blob of greys and aquatic blues. “I said, ‘It looks like a sea creature,’” says Levy, “And you said, ‘What kind of sea creature does it look like?’ And I said, ‘Well, it could be a hump-head wrasse.’ And you went off that day and, out of that mess, that accident, the book was born. Picasso had his Blue Period, Ralph has his Dirty Water Period.”

Steadman met Hunter S Thompson for the first time in 1970, in Kentucky, where they’d been put together by Scanlan’s magazine to collaborate on an illustrated article about the derby (its publication introduced Gonzo journalism to the world for the first time). Thompson, a drugs and alcohol fiend, never managed to rouse in his friend a fellow love of narcotics. Steadman tried drugs only once – psilocybin – and he can’t remember the experience. “I was a real loser, you know, which is why I think Hunter quite liked me.”

When Thompson killed himself in his Colorado home in 2005 he was 67. Those who knew him well weren’t surprised, Steadman included: back in 1972, Thompson had taken Steadman to Los Angeles to discuss details of his death with a funeral director. “He did say to me, ‘I feel real trapped in this life, Ralph, I could commit suicide at any moment.’ And he had 23 loaded guns in his house. He was always getting pulled up by the Sheriff for driving drunk, and when Hunter committed suicide, the Sheriff got on the phone to all the country Sheriffs. They went round there and all stood round his body, which was on the floor in the kitchen, and they all took one of his books and read one of the pages over his body. Which is quite a moving thing to do.”

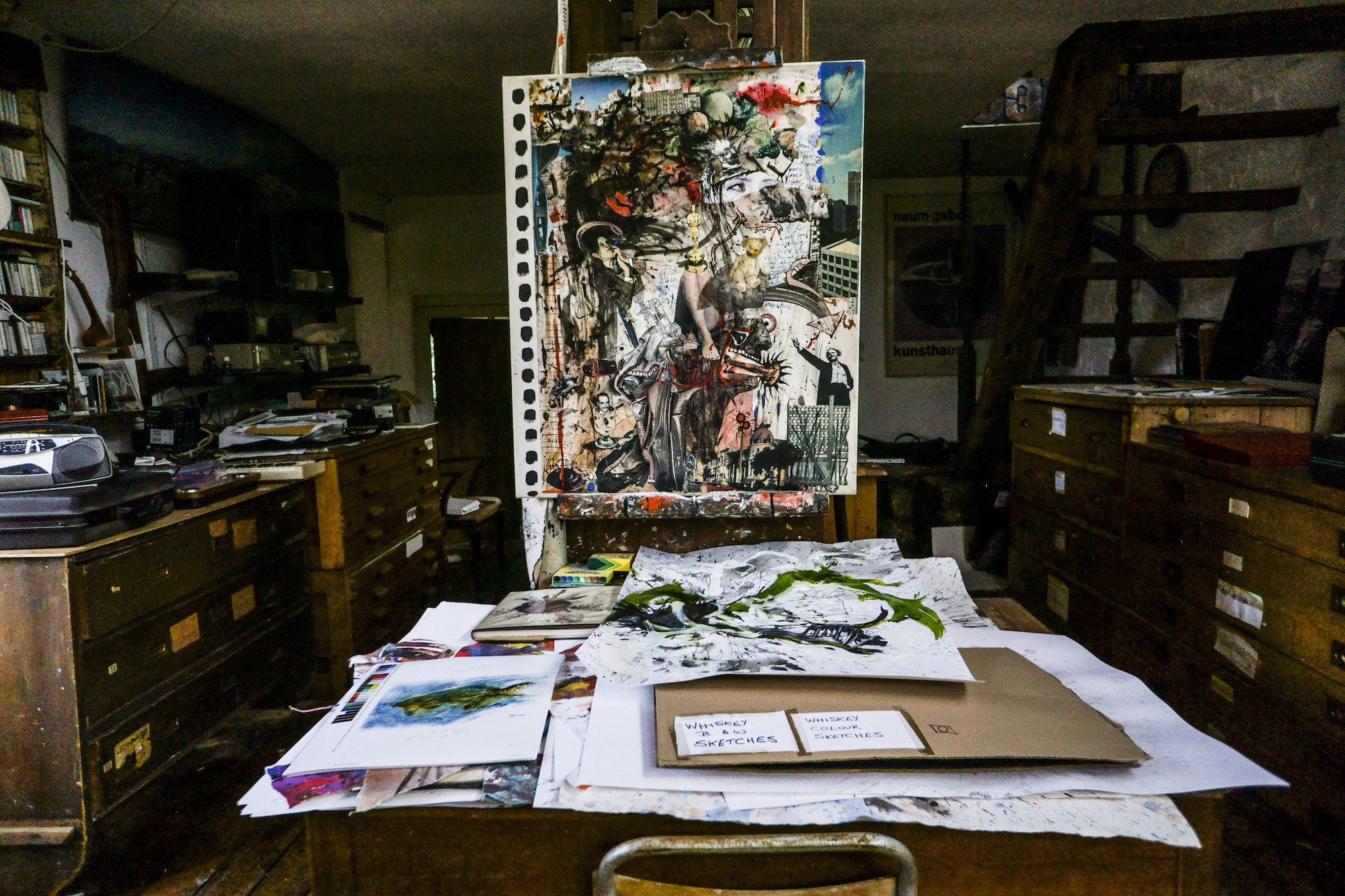

Steadman’s studio is on the other side of the lawn – a fascinating and joyous four-roomed living museum. There are paintings, sketches, sculptures everywhere. His range is so broad, his great talent so blindingly obvious that I feel embarrassed for having associated him so closely with only Fear And Loathing.

As stunning as his newspaper and album work has always been, it looks almost trivial when compared with everything here, or his famous illustrations of works by Lewis Caroll, Freud, Da Vinci, Orwell, or the work he made with Ted Hughes. A formerly cream-coloured rotary telephone sits on his work table, splattered with coloured paint. Beneath it are more incredible artworks, scrumpled up because they haven’t made the grade.

It’s hard not to feel that if Steadman was weirder, hermetic, less astonishingly prolific and more pretentiously grandiose, he’d be recognised not just as a very good artist, but as one of the world’s few very greats.

Right now he’s busy singing along to a tune he’s playing on an old tape cassette deck while Sadie shows me around a room at the back. Correspondence between Thompson and Steadman most often took place by fax: the sound of paper spooling out of a fax machine in the middle of the night is the sound of Sadie’s childhood. They’re all still here: “Hot Damn, Ralph,” reads one, “It’s you and me on the cover of Rolling Stone.”

“He was vicious, but dad gave as good as he got,” says Sadie. “Hunter came to stay with us once for two weeks, and by the end of it mum was on Valium and I hadn’t taken my coat off for eight days.”

But it’s time for us to go. Outside, Sadie’s children have arrived for a swim. How do we save the world? “Stop shooting things, that would be a good one,” suggests Steadman. “Become Gonzovationist,” says Levy, and the two men merrily wave us off from the drive, laughing as they begin another string of absurd and affectionate jokes of the kind that might one day go some small way towards saving the planet.

Critical Critters by Ralph Steadman and Ceri Levy is published by Bloomsbury, £35 on the 27th of July.

More on VICE:

The Political Art That’s Actually Worth Your Precious Time

Ten Years After Hunter S. Thompson’s Death, the Debate Over Suicide Rages On

More

From VICE

-

(Photo by Lakeshow_323 via X) -

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

Collage by VICE -

Archival photo from the 1996 World Conker Championships. Photo by Mark Thompson/Allsport.