Master P / Photos by Daniel Brothers

In Rank Your Records, we talk to members of bands who have amassed substantial discographies over the years and ask them to rate their releases in order of personal preference.

Videos by VICE

We talk about a lot of musicians as if they are larger than life, but Percy Miller, better known as Master P, really is the stuff of legends.

If there were a movie made about his life—according to him, there is one in production—you wouldn’t believe half of it was true. If there were a Grand Theft Auto-style video game about his life—which he also says is something in production—you might find it unrealistic. He came out of what might charitably be described as a colorful street past, growing up in New Orleans at a time when it was one of the most dangerous cities in the country. He helmed No Limit Records, home to such artists as Mystikal, Silkk tha Shocker, and, for a period, Snoop Dogg. It would become of the most influential labels in the history of rap, quite literally changing the blueprint for independent music and turning the nation’s ears onto the South in a new way. He launched an accompanying array of business ventures that included No Limit Films, No Limit Sports, and No Limit Comedy. At the height of his career, he went to play professional basketball in the NBA D-league.

And, of course, he made music. Lots of it. More songs and albums than I or Wikipedia or even he would fully be able to account for. And they sold by the millions, especially in the late 90s, when albums like Ice Cream Man, Ghetto D, and MP Da Last Don became multiplatinum, international phenomena. Songs like “Make Em Say Uhh,” “Bout It Bout It,” and “I Miss My Homies” left an indelible imprint on music that went far beyond their success on the charts, which itself was not inconsiderable. Master P is not always listed among rap’s greats, presumably because we haven’t yet developed the vocabulary to process his prodigious output. All we can say is “uhh.” The guy made the tank logo more famous than a century of military technology ever could. How do you begin to talk about that?

So. Here we are. It’s been 20 years since the release of Ice Cream Man, more than a decade since the dissolution of No Limit Records. But No Limit is forever, and so now there’s a label called No Limit Forever, and Master P is grooming a new set of artists called the No Limit Boys—Lambo, Ace B, and MoeRoy, themselves larger-than-life characters in the making (Lambo, for instance, is married to LeBron James’s mom). He has a new album on the way called The Grind Don’t Stop, with a single called “Middle Finga,” featuring the No Limit Boys.

“I’m like Benjamin Button,” Master P quipped on a recent visit to the VICE office. “I’m getting younger and getting better at this.” He explained the song: “Somebody could tell you your career and your time is over—put the middle finger up to ‘em.”

P’s career has been a series of middle fingers to what people might think is possible. So, with that in mind, even as he looks forward, we asked him to look back and reflect on his discography, ranking his albums from Best to The Point Where He Got Tired of Ranking Them Because There Were so Many. This is what he had to say:

11. Game Face (2001)

Noisey: What’s the story behind this one?

Master P: Had to put my game face on, ’cause I balled in the NBA. I played with Steph Curry’s dad, Dale Curry. Nice to put it on him in practice. He’s a hell of a shooter, there. You know, the difference with me, if I know you can shoot, you not gon’ shoot that ball on me. I’ma hurt you. I’m trying to hurt this man in practice, like you’re not about to make me look bad like that, ’cause he was a sharpshooter. I see why his son’s so good. I tried, as soon as I get him, I fake at him, fake like I’ma hit him or something. So throw a shot off. Why they don’t do that in the NBA no more?

I was really a hitman in the NBA. I played with Vince Carter, Tracy McGrady, Charles Oakley—that was my homeboy, you know. All we did was shoot dice the whole season. I think he still owe me some money, I gotta find out. But look, when I get in, the coach would tell me, “you know that boy be scoring 30, 40 points a game.” I said, “which one, coach?” ‘Cause I ain’t worry about who the names; I just worry about the numbers. I’m going put to pain on em. I remember, actually, Sam Cassell. Sam Cassell would tell the coach, “take me out, they about to put P in, he gon’ try to hurt me.” And that’s how I played. We played real ghetto basketball in the NBA. Can’t tell y’all about the fights I got into in the NBA. But I did had a couple, and I was undefeated like Mayweather. I’m just letting y’all know. I didn’t lose one fight. I asked the coach, I did it politely. I said, coach, whatever happened in the gym, stay in the gym. He said yes, sir. I think he wanted me to beat up a couple people—

You would fight your own teammates?

My own teammates, man. Because let me tell y’all what happened, right. So y’all know in the NBA, you gotta carry the bags. The rookies. Well I make too much money, I ain’t carrying no bags. They say, “why P can’t carry the bags?” I say, “I’m a super rookie. Super rookies don’t carry no bags. I make more money than all y’all. Carry my bag.” It was like man, we gon fight when we get back to the house.

I grew up in the project fighting, you think I’ma let a basketball player beat me? All the fights I done had, look. Knuckles all broke, everything. You think I’ma let them beat me? Look at this. I been in apartments fighting my whole life. Look, still got bruises on there. You think that I’ma let a basketball player—now, one dude I was kind of scared of him. Anthony Mason, rest in peace. In Charlotte, he told me nobody better not touch him. People were scared of him in practice. Me being from the projects, as soon as somebody say that to me, he go in for a shot, I slapped him, bow! He said, “little man, I’ma beat your ass.” I said, “man, you want to do it right now?” He said, “no, when we get in the locker room.” You know me. The dude’s about 6’10,” 307 pounds. I get in the locker room, I’m already squared up. Saying, are you ready? He said, “little man, you crazy.” We ended up being friends after that.

I ended up getting cut behind that, ’cause the GM wanted to know, “P, why you ain’t scared of Anthony Mason? ‘Cause I’m scared of him.” I said, “Sir, I ain’t scared of nobody.” He said, “well this a Bible Belt city, and your music is pure filth, we gon’ have to go a different direction.” Then they cut me. I was the last cut on that team. Now you could imagine this Jewish guy that’s running Charlotte, listening to the Ice Cream Man. You know, once that came on—“fuck, shit”—“oh, what is this?!” I just packed my bags. I said, I know they about to get rid of me. If that man there listened to my music, I’m out of here. I’m done. I’ma pack my shit up before they told me. Yeah. It’s a wrap.

Who would you say is tougher, basketball players or rappers? ‘Cause you probably fought a few rappers in your day.

I don’t want to talk about the rappers I fought, but it’s cool. I treat every man as a man, ’cause where I’m from—I’m from New Orleans, at that time the murder capital of the world. Even gay people will shoot you. I used to go and laugh and stuff, ‘cause I seen this big old guy, about 6’7”, he had a miniskirt on. So I walk into the Walgreens, and I started laughing. The boy had a gun, he went in his purse said, “ha ha ha, who you laughing at?” I said, “miss, I wasn’t laughing at you.” I knew he was gonna pop me. I left that alone right there. I don’t even play. I respect gay people, everything after that. Got my mind right. I done seen a couple of them kill some people down there in New Orleans. I don’t disrespect nobody. I don’t care how little, how small, or whatever. I think everybody, this a free world, everybody could be whatever they want to be. And shout out to Ellen. Yeah, she from New Orleans.

10. Ghetto Postage (2000)

They put me on the stamp. I don’t know how many places it reached, but I got on a real stamp on this album, so, you know, I’m like, man, a kid from the projects on the stamp! Go and put me in the post office!

How did that happen? How do you get on a stamp?

I don’t know. I don’t know. Yeah, it’s like, how do you do that? You know what, God is good, he give me seven chances, and I feel real good.

9. Ghetto Bill (2005)

You’ve heard of Bill Gates. Got my money real up, so, it’s like, you know, time to be the ghetto Bill. Made Forbes, made a bunch of things, so, you know what? Let’s go on and show the world what we got. Let’s show ‘em the gold ceilings. Let’s show ‘em some other stuff that we done good and we been able to do this.

8. MP da Last Don (1998)

That’s when I realized—with the Godfather movies and everything else—why not a don? Why not a black don, you know what I’m saying? I could speak that language, I could speak that Corleone, welcome to the mob life. I done been through it all. I done paid my dues.

That one has a really iconic cover too, of you in the whole Godfather getup, the kiss the ring kind of thing. How did you come up with that?

I mean, you a boss, you a real boss. I had to go get the Versace suit. I had to get the gator shoes. I had to go and compete. I made a movie with that album, and I felt like the world needed to see the boss moves that I was making, taking over the music industry. Being from the South, being a country boy, watching what Rap-A-Lot—Lil J and Scarface and the Geto Boys—did, they kind of opened the doors to one piece of the South, and I feel like I opened the doors to trap music. They had the ridin’ type of street music. Scarface made you think. And I feel like, with the “Make Em Say Uhh”s, it woke people up. It was down South, dirty, drill sergeant music, where you just had to jump up in the clubs and party.

I mean, I opened to a white fan base. I went to one show, it was 30,000 white kids. I’m asking the promoter, “man, you sure this is my show?” Like man, you’ve gone and set me up. What’s going on? I was spooked! I was scared! It was like, you know, you show up, I’m in Tyler, Texas. Dude’s, “they love you out there P!” I say, “what you mean, ‘they’?” Man, it was 30,000 white kids, and I start singing “Miss My Homies”: [Singing] “Sittin in the ghetto thinking bout, all my homies passed away, uhh.” They was going crazy. The whole crowd sang it word for word. Then I went to Denver, I’m like, man, y’all tripping. Y’all sho? That’s when I realized. It started after Da Last Don. After this album, it went international. Like, people in China started hitting me up, “we love you! Last Don, I loved that record!” And I’m like—man, it was crazy.

That is crazy. Have you played in China?

I’ve been to China, but I’m going to play China. I feel like China is almost like ten years behind, like now I can go to China and sell out an arena. I’m getting kids in Russia now, loving my music. I just got a kid in Russia who just redid the Master P song, and other countries is going crazy now.

7. Only God Can Judge Me (1999)

I figured that, you know, only God can judge me. Whatever I did—I used to be scared to go in the church house. This when I really found God, like, man, he had a murderer, he had a prostitute he saved. I looked and read the Bible, and then next to Jesus he had all these people that did mess up, that didn’t live a perfect life, and then he forgave ‘em. And that’s when I started picking up the Bible, and I realized only God can judge me. Like, no man can judge me. ‘Cause nobody know what I been through, nobody know what my pain is. Nobody know all the people I lost.

6. 99 Ways to Die (1995)

1995, 99 Ways to Die, I’m thinking, man, what’s gon’ happen to me? And this record I made, 99 Ways to Die, is—it changed the way that I thought that what might happen to me. And I surpassed that, like I said. My goal was to live to be 19. And I have my own business, and I want to motivate kids that, even though this record called 99 Ways to Die, there’s 99 ways that you could live, if you change your life. So me changing my life—

What songs do you feel like were—

Well, I don’t think it was a complete song, ‘cause that whole album was about the struggle and the pain and losing so many friends and being out there on the block. At that time I was in Richmond, California, hustling and selling CDs out the trunk of my car. So being able to give that hustle game, and put it in the music, instead of something negative.

How’d you end up out there?

I was on the run. All right. [Laughs].

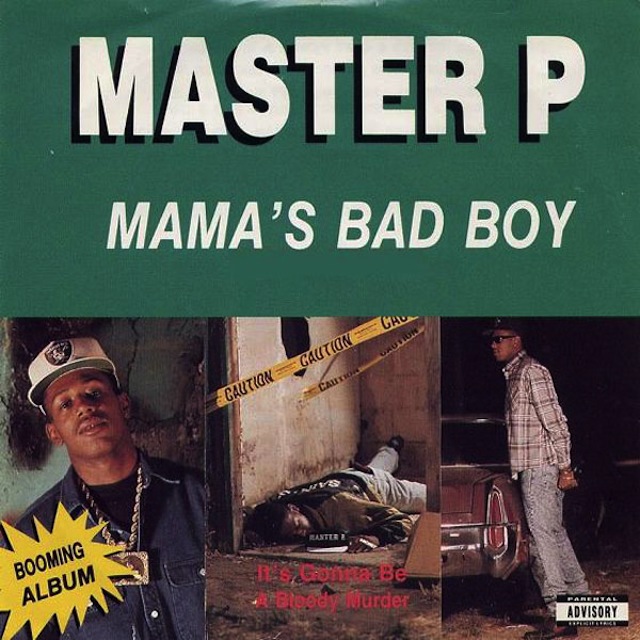

5. Mama’s Bad Boy (1992)

Mama’s Bad Boy. It was like, man, I put my mama through so much hell. You know that song that 2Pac got, “Dear Mama”? I think Mama’s Bad Boy my whole album was trying to let my mama know that I love her and I appreciate her because I put that woman through a lot. You know, because I was out there in them streets.

Do you think the message got through to her?

Yeah, it got through to her, but she kind of lost it when my brother got killed. And that’s when I knew, I knew I had to change my life.

When was that?

That was—I try not to even think about it no more, man. I try to just move on.

4. Get Away Clean (1991)

I’ma go to something that y’all probably don’t even know. 1991, before that, Get Away Clean. The album cover with the two little circles on there, the orange album cover with the two circles. I was jumping gates. That’s the only thing I could tell y’all. How many years it been since this? Is the statute of limitations up?

Twenty-five years? You’re probably safe.

No, I’ma wait about three more years before I tell y’all about that. That was my first record, making it out of a bad environment, thank the man up above.

What inspired you to record? What was your motivation at the time?

Man, so you see me jumping over gates on that cover. So picture me jumping over the gates, running from… life. Running from things that the average kid that should be in school doing homework and preparing to be the next doctor, lawyer. I was a pharmacist. Just think of that.

I was recording anywhere I could go: In K-Lou’s garage, his mama’s garage. Like the ladies would be like—‘cause I think his mom was a church lady, and when she heard me, she like—“oh, what is going on back there?”

What was the garage like? What was the set-up there?

Man, it just was a garage. He had put the little speakers and the little four-track, an eight-track back there. And we was making music. But it sound crazy. I’m cussin’ every other word, and this lady’s a church lady.

And then, you know, in New Orleans, I was doing my music in the bathroom, in the project on a four-track. So I had a little guy recording me, and then I got the shower thing for the mic booth. It was crazy.

3. The Ghettos Tryin to Kill Me! (1994)

I’d been through so much when this record came out. I didn’t think I was gon’ make it. My goal was to live to be 19, and a lot of my friends was dying at 16, 17. And I didn’t think I was gonna record. So to be here 20 years later to see the Ice Cream Man anniversary, this record, the Ghettos Tryin to Kill Me, I was definitely trapped in that life, in that world.

I was in poverty. You walk out your door, you might not come back home. You might go to jail, you might get killed, so that’s where the Ghettos Tryin to Kill Me. [Rapping] “The ghetto’s trying to kill me, they might send me to the pen but doing time, that don’t scare me.” So, I was going crazy then. I don’t think you wanted to see Master P that year. 1994, I was a whole different kind of human. Big man up above—Thank the man up above that I changed, and my life changed. But I was a different kind of animal.

What would you say to yourself then, speaking now?

Oh man, what is you doing? How you living like that? I’d come out the house man, with two straps on me. Like, just wild. And I was living like that, running from the police. Everything you could think of, I was just trapped in the middle of. I started making music ’cause I was thinking I wanted a way out. You might not know a lot of these young rappers, what they going through. That’s the environment. So that’s what I mean, the ghetto’s trying to kill me.

2. Ghetto D (1997)

We taught the world how to hustle on this record. You know, how to go out there and get your money. We talking a lot of other things, but we’re also talking the pain and the struggle that you can overcome there.

I was in the state of mind that I wanted to be the biggest artist in the world, and that Ghetto D record took me to where I can compete with all other platinum artists out there in the world.

Do you remember what it was like in the studio recording that album? That’s the height of No Limit.

Yeah, definitely the height. It’s like—being in the studio, being in there with C, Silk, Mystikal, Mia, Fiend, Mr. Serv-On, KLC whipping up the music, K-Lou—I mean, man, I feel like, invincible. Nobody could stop me, because the words, what I’m talking about, is real, I’m living it. And so to be able to give that to the world to see: This what a real trap star live like, and we want to change our life. Ghetto D opened the doors. That was the record I got the world hooked, I got the world high on Master P.

Do you remember what it was like when “Make Em Say Uhh” broke out, or what it was like recording that song?

Well, for me, my brother had died, and “Make Em Say Uhh” was—we come from the streets, we don’t tear up and [pray upon?] your loss, like some men—that was the way I showed my emotion. The “uhh” was emotion, was the soul of me losing something that I loved. So that record really brought that out of me.

1. Ice Cream Man (1996)

I feel like this the project that put me on nationally. This is the project that opened doors for trap music, for street hustlers to be able to get opportunity to make money off of music: Own businesses, be they own bosses, get in a professional sport. I played basketball. People know I hustled in the hood. People know who the Ice Cream Man is. I changed my life. This the record that did it.

I started feeling like I made it, ’cause I’m in a real studio now, doing the Ice Cream Man, with real people. Some of those records I recorded, I had crackheads standing outside, they’d be knocking on the window, and I was in a whole different environment. I could hear em say “y’all better shut up before P get mad and come out here.” You would hear some in the music. That’s how we was living, we had nothing, that’s all we had.

I thank the man. I wouldn’t wish that type of life on nobody. But I thank the man that I had education, and I played basketball, I was able to see a couple of things. And I think I had a lot of older people praying for me, and I think that spared my life. ‘Cause a lot of my friends died young. A lot of em. If you listen to “Ghetto Heroes,” it’s about 107 people—these were personal people that I named in that record, that I knew. By the time that record came out, they was dead.

I start getting immune to death. Like, I didn’t even cry at funerals no more. You know, I just started putting it in the music. Because I seen it so much. What happened to me, I think what changed my life, my grandmother put a black dress up, over her dresser, so she’d know I was out there wilding out, she said, “boy, I’ma wear this to your funeral.” And everything changed. I’m like, man, I gotta go. I packed up my bags, I took Romeo, and we just moved. We just went to California. I said, “I’m going to California. I’m not gon die here. This not ‘bout to happen.” I think that’s what saved my life.

Were there any songs that you feel that didn’t get the attention they deserved?

I feel like “Break Em Off Something” didn’t get the love that it was supposed to get ’cause I never shot a video for that song. But it’s one of the biggest records in the club, to this day. So imagine if a video would have been made for that record. I remember, I had made those lyrics even before the record was made. I used to walk in the project and just be singing because what I see out—music for me, I don’t write. It’s a feeling. So I used to walk through the project and see what I see. So I’d be saying, [rapping] “Hustler, baller, gangster, cap pealer / Who I be? The neighborhood drug dealer.” And it was like, when I finally heard the music, when they cut the music on, I just went straight to it and it just poured out.

Why do you think it all came together on that album? What was it about that moment that was so special?

It showed the versatility that people had to respect Southern hip-hop. ‘Cause at that time it was about the East Coast and the West Coast. I was opening up for 2Pac, and to be able to go national, for me to be able to take my music nationally, that was a whole ‘nother thing.

Daniel Brothers shoots video and still pictures for Vice. Follow him on Instagram.

Kyle Kramer is an editor at Noisey. Follow him on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Xbox Game Studios -

Screenshot: Sony Interactive Entertainment -

Screenshots: Bethesda Softworks -

Screenshot: Sony Computer Entertainment