This article originally appeared on Noisey UK.

Like hair that’s been styled for a Smash Hits photoshoot with an entire bucket of wet-look gel, or rock bands with a member who plays the turntables, CDs are a near-dead species in modern music. According to the BPI, while there were 11.5 billion streams recorded in the first six months of 2015, CD sales in the United States dropped by a third during the same period, and they continue to fall in the United Kingdom also.

Videos by VICE

Going through your mate’s dad’s CD wallet and discovering just how bad 90s Springsteen was seemed like a rite of passage, but now, thanks to the Internet, every band’s entire oeuvre is at your fingertips. I can’t remember the last time I bought a CD, ripped the cellophane from its packaging, and leafed through its booklet of dodgy song lyrics and thankful mentions to the record label executives that supplied the steady stream of cocaine to the band’s in-house studio. Like most people, I consume all music online at all times: cruising through YouTube videos, Soundcloud streams, Spotify exclusives, and that forgettable month when I signed up for Tidal.

Thanks to all this, it might be easier than ever to get your music out there without the backing of a label and a PR company, but it can still be difficult for a new or unknown artist to get their music into the actual ears of the general public, and not just some bedroom blogger from Amsterdam. Some artists have tried to garner fanbases with things like crowdfunding proposals where you don’t just get a CD but you also get your name in the credits, a voicemail on your birthday, and a signed poster saying “cheers mate”. Others have tried to limit the amount of physical copies they produce so that their CD becomes something of a sought after artifact, like Nipsey Hustle who only made 100 copies of his mixtape but sold them for $1,000 each.

But out there, on the streets, there are still some musicians doing it the old school way, working hand-to-ear in giving their CDs out on the venue steps and town squares of Britain, Europe, and America, to absolute strangers. I’m talking about street mixtape rappers.

In the year of our digital lord 2016, it’s interesting to consider why these artists continue to stand on corners, struggling to give away a piece of plastic with five low bitrate MP3s burned on it. What do they gain? Does it make money? Can it actually lead to success? And is it fulfilling? For a few months, everytime I met one of these rappers on my travels, I stopped, chatted to them, and took their photo. This is what I discovered.

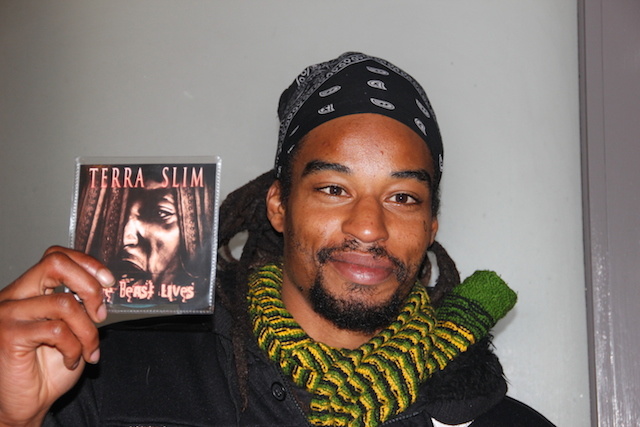

Terra Slim

I met Terra Slim outside Camden’s Jazz Cafe in North London. A veteran of the game, Slim’s been selling CDs on the street for over a decade. In that time he reckons he’s “got rid of well over a hundred thousand of ‘em”. To put that into perspective (and to take his claim as fact), that means he’s shifted as many units as Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly has to date. The music Slim makes isn’t particularly fashionable: it’s the sort of socially conscious UK hip-hop that reeks of sticky weed and discarded Rubicon juice cartons. Which is to say, it’s the sort of music that doesn’t tend to get picked up by the outlets who post online.

Yet despite the public’s listening habits changing, Slim believes he can get people to listen to his music by giving his records out directly on the street. “Less people actually listen to the CD,” he tells me. “There are some people who genuinely don’t have a CD player now.” Instead, Slim says the act of handing out the CD prompts the person to go online and search out his music for themselves. Despite this, he does manage to make his living from mixtapes. That’s right, while we’re slowly being sterilised by office screens, he’s on the streets for around four hours a day selling his wares, and making some dosh. Well, “depending on the weather” of course.

Slim was born in South London and moved around the capital, before his parents settled in Watford. In 2005, when he was old enough, he moved back to London and released his first album. “I started selling CDs on the street for money,” Slim says, “one of my mates was a DJ and used to put these compilation tapes of popular tracks together, so I pushed them for him.” After a trip to New York he noticed artists selling their own music on street corners and thought he’d give it a try. “I didn’t think it’d work for my own music,” Slim said, “but you know what? It did.”

Slim goes out with around 100 CDs, apart from on the weekends when he takes more. “It varies how many I sell,” he says “but on average it’s around 20 or 30 a day.” The prices vary, but they sell for around a fiver. According to Slim, it has a direct impact on his fan base, with many people he meets liking his Facebook page or following him on Twitter. Before our chat though, I saw far more people simply ignoring him or not taking his mixtapes. “The way I see it, as an artist you don’t want everyone to like what you’re doing,” he says. “Everybody has so much going on you can’t take it personally. People are just trying to get where they’re going.”

Scarshots

Unlike Terra Slim, Scarshots makes music with a somewhat aggressive edge. The mixtape he gave me when I met him outside the Electric Ballroom isn’t online, but there are a few tracks and a number of freestyles floating around. My favourite is undoubtedly “Don’t Fuck Wit Me”, which uses a sample from Jai Paul’s “BTSTU” as its backing track. Scarshots had been rapping for about six years when he realised he “should be proactively out there.” Without a manager or a label, I ask Scarshots how often he plays live? “As much as I can, mate, I go all over. I’m going to open mics, clubs or pubs, whatever”. Though he admits: “There ain’t many places that put new rappers on anymore.”

Timypiri

Timypiri, a musician and creator of clothing label Abandoned Kulture, also sells his CDs on the street, but has taken most of the tracks from it offline. When we met up on Camden High Street he said: “I thought the only way I can show my music to the people and at the same time, you know, make some money with my product, is to be out on the streets and just do it.” I realised that Terra Slim wasn’t an anomaly. For quite a few of the rappers I was meeting who gave out tapes on the street, a surprising amount actually make a bit of money doing it.

King Pin

Take someone like Tottenham’s King Pin. He studied English Literature and even had a mini-documentary for Channel 4 filmed about him and his vegetable patch (literally) called the Rapper’s Guide To Gardening. He’s put out two albums of politically and socially conscious hip-hop, which you can find on Spotify or on his Bandcamp, yet he started selling music on the streets a couple of months ago to bolster his burgeoning career. And it’s worked. Since he’s started selling on the road, he’s shifted over 700 copies. When you consider that money has gone straight into his pocket, without the need to pay labels, managers, or PRs, that’s way more dollar than selling 700 EPs on iTunes.

Kig David

No matter what Lionel Ritchie might say, the music game isn’t easy. When you’re an indie or electronic artist, it’s hard enough to get a break, but at least there are thousands of venues across the country you can gig in to get attention. Urban music just doesn’t have the same access. Hell, just consider the 696 form, which was used by the authorities to shut down events deemed “risky”, actively discriminating and demonising certain genres and, with it, demographics. Just earlier this month, a secret crackdown by police on venues playing bashment music specifically was uncovered in Croydon.

It’s the lack of live opportunities and the dearth of major label attention drives the artists to go out and kickstart their own career on their terms. It’s kind of like that scene in Pulp Fiction, but the musicians are John Travolta, the streets the needle and the public are Uma Thurman’s heart. Strained metaphor aside, each rapper I met truly believed that they were furthering their cause by selling mixtapes and, on some level, they’re absolutely right. A brand new Lambo and a house in Chelsea might be out of their reach, but with living costs in London rising by 40% in the last ten years and many artists in the capital struggling to survive, it’s a minor miracle that these guys are making any money at all. Whether it was circumstance or choice that led them to push their music on the street corner, the artists are doing something they love and managing to make a living from it. And that’s rare.

More

From VICE

-

Geoffrey Clowes -

-

Rich Homie Quan in 2017. Photo by Larry Marano/Shutterstock. -