Before the internet made it quick and easy to share information, artists relied on IRL tactics to promote their work. Posters, flyers, paper invitations, postcards, zines, objets d’art, and other ephemera represented a populist impulse: reach the masses and give them a taste of what was to come—something they could keep and collect without having to spend a dime.

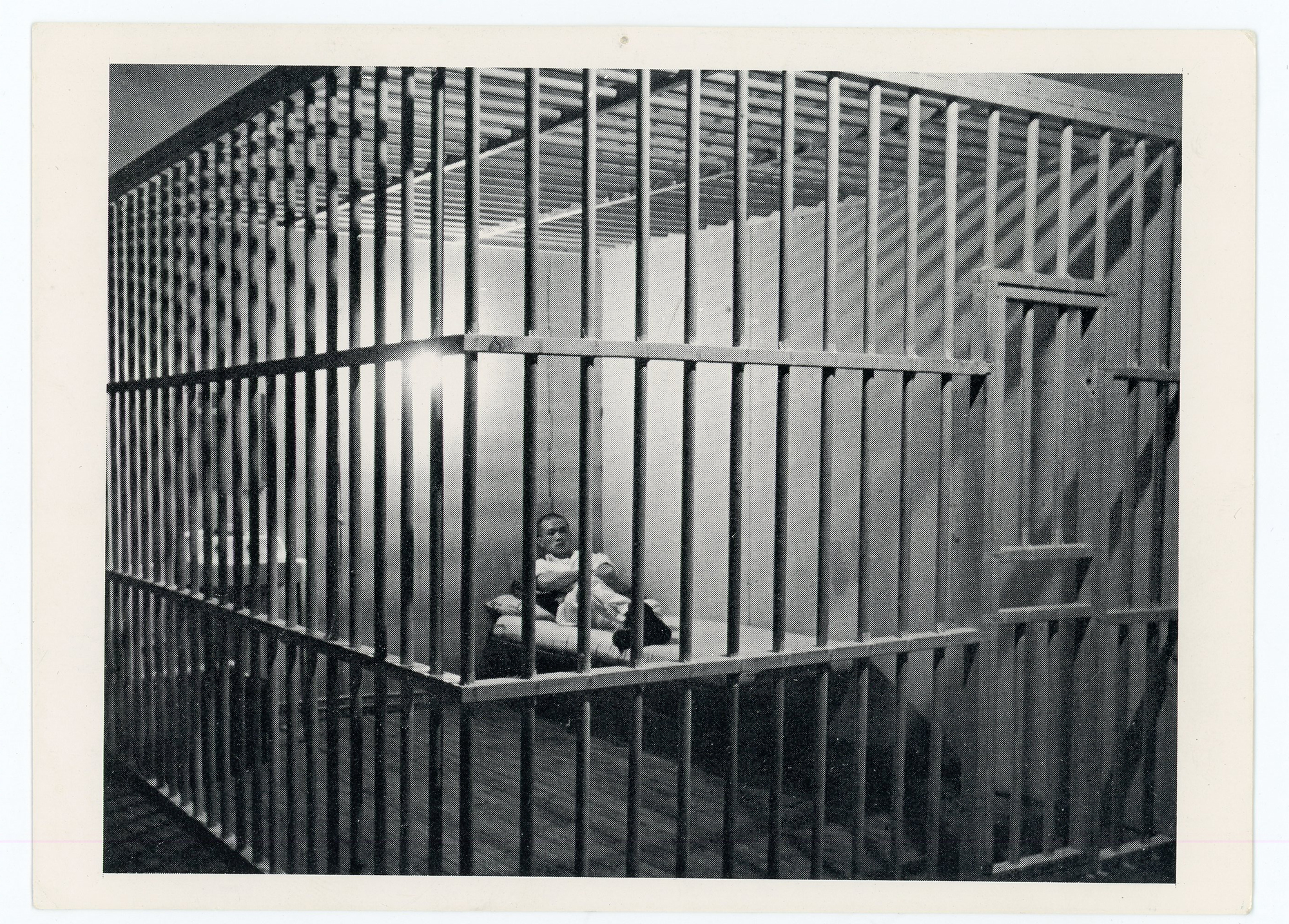

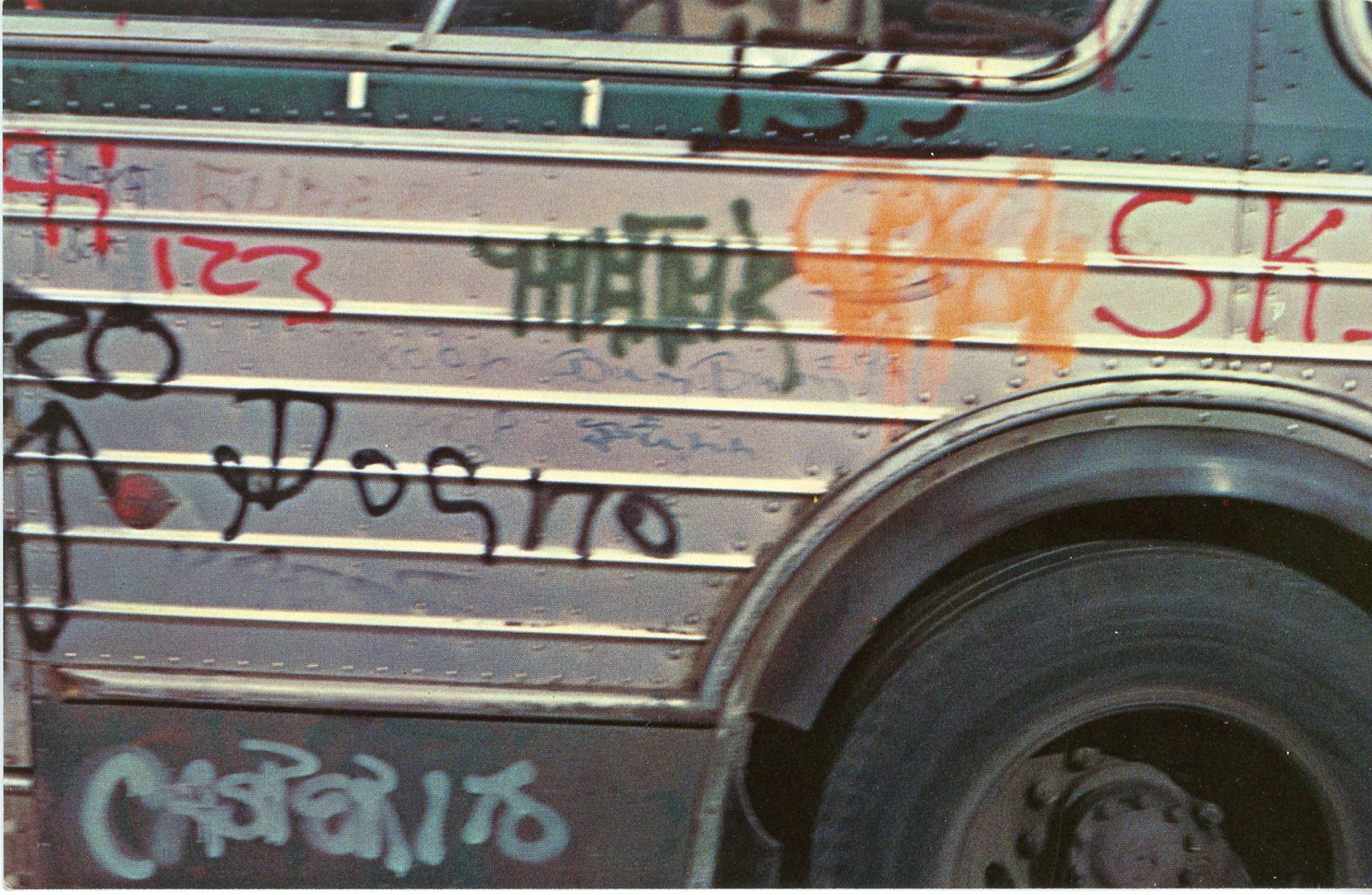

Impermanent art, like graffiti and performance, came to the fore in the Lower East Side in the 1970s and 80s. Art ephemera was often all that remained after a show, and it took on new significance. The materials could be produced cheaply and distributed at will, transforming art in the age of mass reproduction into a marketing tool.

Videos by VICE

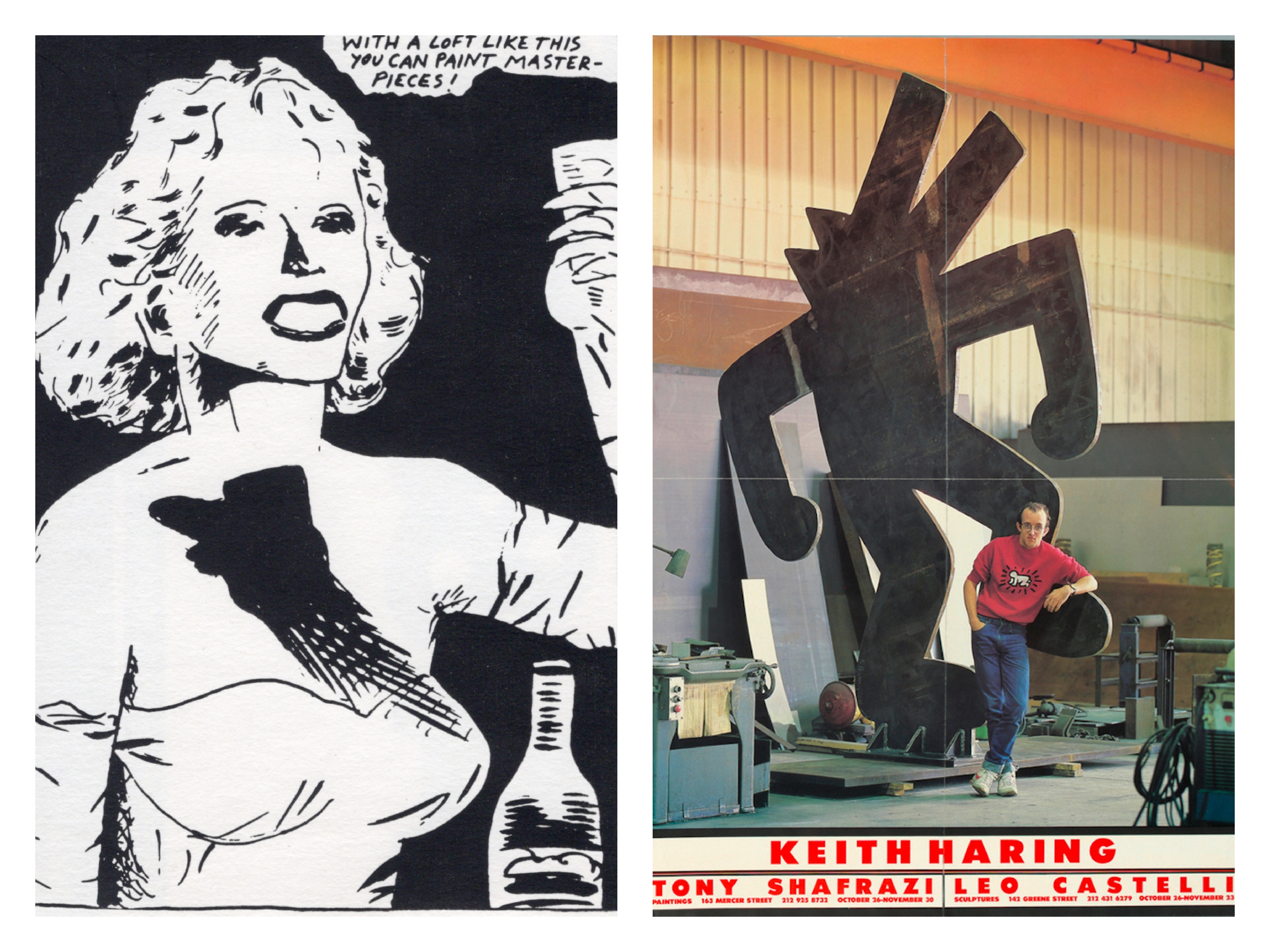

From his studio at 98 Bowery, artist, journalist, curator, and art historian Marc H. Miller amassed an impressive collection of rare ephemera from New York’s storied era of renegade artmaking from the 70s to 90s. His trove contains work by Jean-Michel Basquiat, Andy Warhol, Nan Goldin, Kiki Smith, Cindy Sherman, the Guerilla Girls, Robert Mapplethorpe, Peter Hujar, and Gordon Matta-Clark, as well as galleries like FUN, Fashion MODA, P.P.O.W., ABC No Rio, Leo Castelli, and Tony Shafrazzi.

Nearly 200 items from Miller’s collection are on display in New York this month, in Downtown Art Ephemera, 1970s-1990s at James Fuentes Gallery. To celebrate, VICE caught up with Miller to chat about why these relics from the recent past have such power today.

VICE: Why has ephemera become an integral part of contemporary art history?

Marc H. Miller: During 70s and 80s, artists reclaimed the distribution systems. They didn’t want to reach the limited audience that an elite art gallery represented, and they were hoping to find more broadly based support from larger numbers of people. Keith Haring is the perfect example of an artist who succeeded, and that was a theme that ran through the era: art for the masses.

While galleries were pushing very apolitical abstract or minimal art and trying to sell it to a very small number of well-to-do collectors, artists were getting much more concerned about issues like politics and identity. They wanted to make art that connected to life. There was the simultaneous creation of artist-run galleries, a blooming of the underground alternative press, and venues for artists, performers, and musicians—and the justification of what they were doing lay in political or personal terms.

Within that context, the announcement played a big role. More people were exposed to those ideas through announcements and press stories than were exposed to the actual work of art. They were never really full-fledged movements but there was media art or hype art, where the gist is to get a press response that would allow the message to saturate the society.

How did artists and galleries use ephemera to get the word out?

The only way you could let people know a show was happening was through an announcement or a poster. The art world was also much smaller at the time, so if you mailed out 200 invites, you were reaching a good core of the art world.

Cards were extremely important, especially with a lot of DIY exhibitions where the artists didn’t really expect to sell much but it was important to get their name out. People concentrated on their announcements. Postering became more ubiquitous as a generation of graffiti and street artists came of age. It was also the era of cheap reproductions with Xeroxes, and a lot of artists experimented with making art [that way]. Today we could see it as another form of print, like a lithograph—a cheap way to produce an artwork to be accessible to a large number of people.

How did artists and galleries push the possibilities of ephemera for their respective needs?

I’m thinking of the posters of the 1890s by Toulouse-Lautrec—no one has trouble seeing those posters as artwork today. The ones that survived are cherished. These cards are a little like that. I joke that, “Instead of the art, let’s collect the advertising for the art.” It’s the perfect post-Pop perspective.

Some of the cards are designed by the artists; others are designed by the gallerists. The cards from Mary Boone Gallery, which was the hot Soho gallery at the time, are very interesting; you can see where the artists are trying to project a certain look and feel. I know from some artists who showed there that Mary Boone would literally tell them how to dress. There you are getting an expression of the higher-end art world.

T-shirts present a unique perspective. John Fekner got a t-shirt from Shoreham Nuclear Plant and then stenciled on it a kid fleeing. There’s also the Fashion MODA store section; Documenta 7 was the first time they had a display of artist t-shirts. Keith Haring designed his first t-shirt for them.

How did you start your collection?

The collection is an outgrowth of my website 98 Bowery. As I was creating it, I found how useful the gallery announcements were; they basically chronicled this history I experienced in a very succinct way: names, dates, and an image that gives you a taste of what’s in the show or what the performance is all about.

History is very contentious, especially art history. You have to keep your version out front because everyone experiences it differently. I was seeing the best and experiencing it at its optimum, and I wanted everyone to see the 70s and 80s as I experienced it.

Like anyone during that era, I used to save cards. I’d go out to galleries and pick up cards and posters. They got very elaborate, like the mega posters that Leo Castelli and the wealthier galleries were churning out in a very grandiose way. While doing some research on eBay, I found that these things were relatively inexpensive and convenient to collect. It took off pretty quickly.

At first it was concentrated to my own take on the art world. The show, which is mostly about the 70s, 80s, and 90s in the Lower East Side, is a reflection of that. Then my peers started sharing their collections of cards and I was acquiring them. At this point, I am probably working with collections with over 100,000 cards. I’m happy to see it move into an actual physical space on the Lower East Side—James Fuentes Gallery is on Delancey Street.

Can you speak about the importance of preserving ephemera from a historic and financial viewpoint?

I am an art historian with a Ph.D in art history. And the great nerd joy here is going through these piles of cards and reliving those years. I started the site to propagandize certain types of art that I knew, but beyond that it’s a research site. Things get marked sold, but I keep the objects up there because it’s important for that information to stay out there for people researching art and ideas.

Everyone is complaining about the price of art centered around a few artists going for prices totally out of reach. Ephemera is a tier of the art world where the financial involvement is lower. For art lovers who have a collecting impulse, this is a way they can own actual vintage works [related to] the Andy Warhols, the David Wojnarowiczs, and the Jenny Holzers that they’ve grown attached to.

Much of it is highly collectible. At the moment, there is a Basquiat mania so those cards go very quickly. To be able to own an actual card from his first show or the invite to the memorial service, these are ways to connect to the artist in a strong way. I can’t hold onto graffiti stuff. It’s an ephemeral art form itself, so the cards and the posters have a bigger place in that culture. People can put together whole collections around certain artists through the ephemera.

Could you speak about the enduring appeal of ephemera?

There’s a nostalgic aspect to this. James Fuentes grew up in the Lower East Side so he experienced a lot of this as a kid; then his parents moved to the South Bronx—just like Fashion MODA. One of the artists he shows is John Ahearn; John’s sculpture, Double Dutch Girls, was hanging on a wall in the neighborhood when he was a kid.

Ephemera contains the seeds of a lot of issues and influences of the times today, so it cuts across multiple generations at the same time. For example, we have materials from the Guerilla Girls and A.I.R., the first women artist cooperative, which was established at a time when women were trying to get their work out there and feeling the disparity of the reception. There’s a phenomenal history of art here.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Miss Rosen on Instagram.