For the past year and a half, eight men and I have been taking part in the first creative writing course offered at the John B. Connally Unit, a 2,500-men maximum-security prison in southern Texas. It is one of over 110 prisons in Texas that together house 143,000 men and women.

During the time that we’ve been a part of the creative writing course, we’ve written many, many stories, spurred on by our teacher Deb Olin Unferth. We’ve written about our jobs, our fights, the glaring cell lights, the giant fans, mail call, Texas sunsets, life sentences, and about years going by. We write about sons and daughters who don’t visit, mothers who come every week, barbed wire rolling out “like a slinky” (as Jason describes it), about what it feels like to be called “offender.”

Videos by VICE

The Connally Unit has been my home for more than nine years now. During my time here I’ve done all I can to better myself and to make the best of my situation. I’ve attended numerous programs and religious classes over the years and I’ve learned much from them. They were helpful and informative, but it wasn’t until I started the creative writing class that I felt like I was doing something worthwhile.

This class has helped me in so many ways. I’ve found healing, a way to live with my situation, and hope. The class has allowed me to be heard, to leave behind proof of my existence, and has given me a way to preserve my name. I no longer feel like I’m just a number—I now have a voice.

The class is not without its struggles. Just getting to class at the education department can be hard in a world where you have to pass checkpoints run by desensitized guards. I wasn’t able to attend my last class for that very reason. Then there are the lockdowns, canceled classes, men being shipped to other units without warning or ceremony, cellie issues. Even paper can be hard to come by.

“This creative writing class has helped me in so many ways. I’ve found healing, a way to live with my situation, and hope. I no longer feel like I’m just a number—I now have a voice.”

Despite all of these obstacles and many more, we still were able to put together our first journal in December 2016: The Pen-City Writers, the name we gave ourselves. This was done thanks to the education department, Windham, who got the journal approved by the warden, and the tireless volunteer efforts of our teacher, Professor Deb Olin Unferth from the University of Texas, who travels two and half hours to get here.

Now in 2017, the class is being turned into a two-year creative writing certificate program. We will each write a thesis, work through a reading list, have opportunities to complete the certificate with honors and to help other men with their writing.

The next two years won’t be without its struggles, but I’m looking forward to it, to all I’ll learn and become. And I’ll get to spend some of it with the other men in the class whom I have come to know and respect as we help each other to become better writers through honest, insightful feedback and suggestions, men with whom I’ve shared my life and have been allowed to share in theirs through our stories, many of which are deeply moving and personal.

The class isn’t what I expected it to be when I first signed up for it. It isn’t a place to hang out, something to do, or a way to pass the time. It’s so much more than that. It has become a passion, a calling, a way of life.

So read on for beautifully written, heartrending, and often funny memoir pieces from our journal—Jason Gallegos’s mournful arrival at the prison, my harrowing religious testimony, and moments of quotidian prison life from Jose Garcia. These are among the first of many stories to come from Connally’s Pen-City Writers, stories we wrote on hot Texas nights, under a moon we see only through cage wire.

—Kevin Murphy

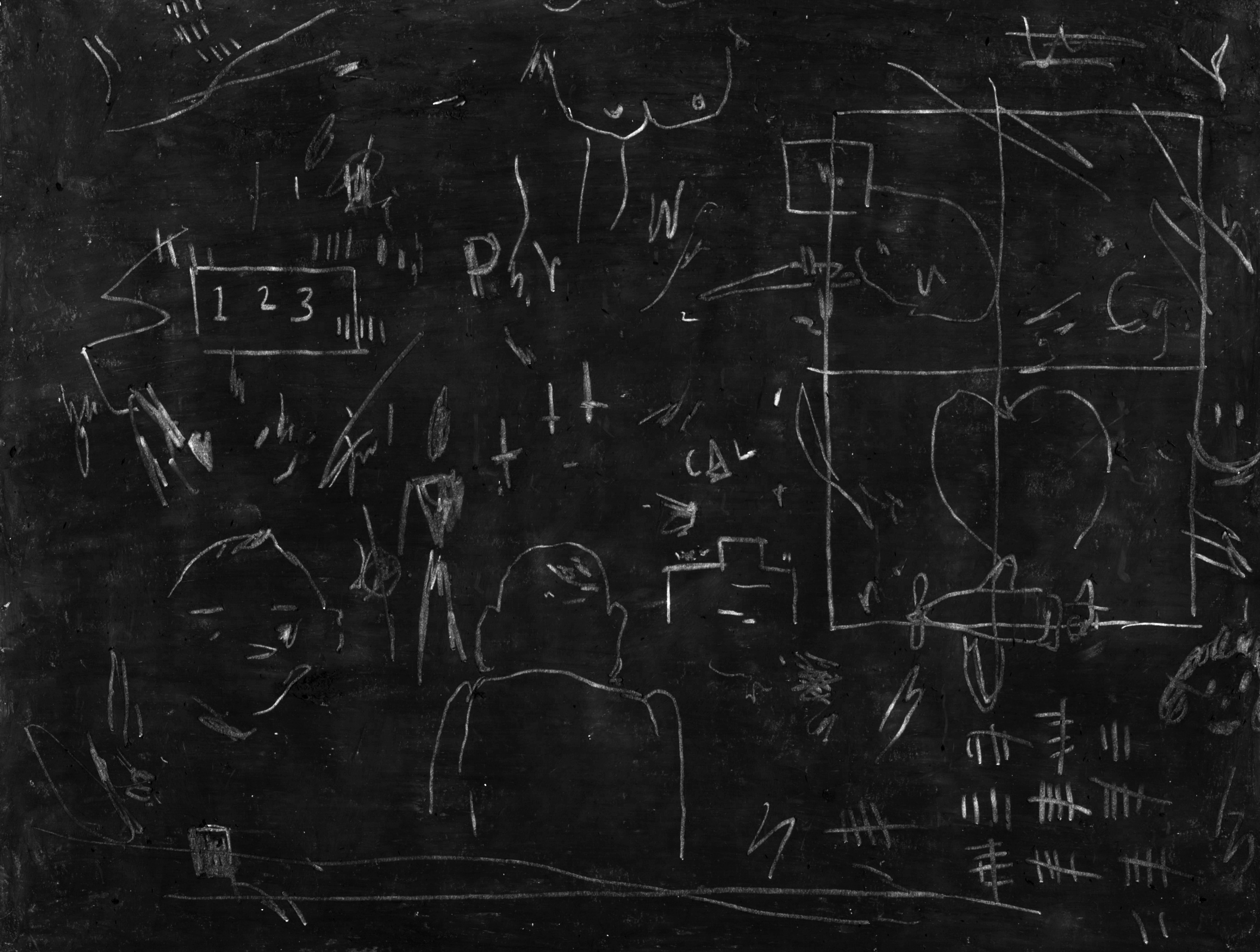

Front cover of ‘The Pen-City Writers’ by Carlos Flores

“Blue Bird” by Jason Gallegos

The time was drawing near for my departure. I had 13 months built up in the county jail. I was convicted and sentenced to prison, and I was ready to leave, to start serving out my long-term sentence in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice Division.

Before my departure, I had the privilege to be laced up by the old-school veterans that had already been in and out of the system most of their adult lives. These convicts prided themselves as they explained in detail what I should expect once I stepped onto the “Blue Bird” that would take me to my final destination, which was prison. I couldn’t help but notice how excited and enthusiastic these convicts were, as they shared with me their personal experience riding on the Blue Bird. It was definitely therapeutic. Their stories eased my fears and they became joyful as they shared their stories.

Their stories enabled me to prepare for what lay ahead.

Doing 13 months in the county jail meant confinement inside of a building with no direct sunlight and very limited movement. I was getting restless because towards the end of my stay in the county I was deemed too dangerous to be kept out in population. So at one point I was kept in isolation for 23 hours out of the day behind a double steel door.

I was only given an hour to be outside of my cell and I was given three options to utilize my hour: shower, recreation, or use a phone. Being in solitary confinement gave me a strong desire to be sent off to prison. At that point I didn’t care if prison was a dangerous place, all I knew by the many stories I heard, in prison I would be able to roam freely, although it would be behind a fortified double-linked fence with barbed wire rolled out like a slinky on top, that stretched all the way around the prison compound. I was ready to go.

Towards the end of my stay in the county jail, I was let out of solitary confinement for good behavior. I was allowed to spend 12 hours outside of my cell to watch TV in the dayroom or spend my time telling war stories among the convicted brethren.

It was March 28, 1998. I was 19 years old and two days shy of my 20th birthday. The day of my departure had arrived. The Blue Bird was finally here to take me to my new dwelling place.

I was called out of my cell at about four in the morning. I had a gut-wrenching knot in my stomach. Not because I feared going to prison, but because I was leaving behind my mom, two sisters, and brother for the first time. I wasn’t able to say my goodbyes. The emotional pain was intense. Inside of me was a young boy crying out in agony for the care and comfort of his mother.

I wanted to be rescued out of this nightmare. My nightmare was becoming a reality. I was feeling the powerful grip the State of Texas had on me, and nobody, not even God, could deliver me out of this situation.

I was placed in a holding cell with about 30 inmates that were also catching chain. Together, we were all going to take the bus ride on the Blue Bird.

I wasn’t very talkative like the others but I was listening intently at the conversations they were having, paying attention to all the faces, and most of them fit the prison mold. They carried on in conversation as if we were all headed out on a field trip.

Then an inmate asked me, “What are you in for and how much time did the courts give you?” I responded to his question by saying, “I was convicted of murder and was sentenced to 50 years in prison,” and everybody in the holding cell got quiet. It wasn’t the word murder that shocked them—it was the mention of 50 years that made them cringe. I realized I was the only one in the group who had the longest prison sentence. There was light at the end of the tunnel for them, but for me prison would become my home.

I kept looking out of the holding cell because I knew the prison guards would arrive at any moment to collect their bounty, which happened to be us.

At a distance I heard the sound of chains being dragged on the concrete floor and the knot in my stomach grew even tighter. The appearance of three white men with cowboy hats, dark ruddy faces, wearing gray uniforms and distinct cowboy boots, stood on the other side of the cell door, looking through the plexiglass window, directly at us with disgust in their eyes.

I kept reciting this mantra in my head, Jason, pretend that you’ve been through this a million times. You are a veteran. Better yet you are a pro. You were born for this. These men are scared, you’re not. The more I recited this mantra, the more sane I became. Courage began to replace the fear that tried to penetrate my heart.

The prison guard began to call out our names in alphabetical order and pairing us up in twos. Once all the names were called out, we were led into a dressing room to remove our orange county jumpers including what I had on underneath, such as a T-shirt, a pair of boxers, and socks that I would leave behind.

We all stood naked, ready to be searched by the prison guards. I was next. The guard stood in front of me and shouted, “Don’t reckless-eyeball me, boy! Run your fingers through your hair! Flap those ears! Open your mouth and stick your tongue out! Lift your arms up and with your left hand lift up your nut sack! Turn around and let me see the bottom of your feet! Bend over and spread your ass cheeks! Now squat and cough!”

Going through this drill made me feel violated but I knew I had to get used to this because it was going to be the new norm for me, from here on out. While I put on my white jumper suit, I felt very cold. I was nervous, and my body shook uncontrollably. We stood in pairs once again but this time in a white uniform. We looked like a flock of sheep being led to the slaughterhouse. One more item needed to be added to my prison costume, which was the shackles. My feet were shackled so close together I was only able to take very small steps forward.

Then a small metal box was used to bind my wrists together. Another small chain hung heavy that kept my hands and feet chained together causing me to stoop over.

The metal door swung open and there it was, the Blue Bird. My eyes were now able to see the Blue Bird in all of its glory. I’ve seen a prototype like this bus many times in those Hollywood movies and I had heard many first-hand accounts by criminals that also rode on a bus similar to this one.

It was time to experience this event for myself. Behind the Blue Bird a prison guard held a shotgun in his hand with the butt of the gun resting on his hip. In a hunchback posture, we marched in pairs toward the bus. The echo of clanging chains reverberated loudly, rattling the drum in my ear. It was a pathetic sight.

I stood in the front entrance of the bus. I had to crawl up the steps of the bus because my hands and feet were chained too close together. I had determined to sit by a window. I sat down toward the center, on the left side of the bus. My window was covered with a 16-gauge metal sheet that had dime-size holes cut into it that allowed me to peer out, as if I were looking through a peephole that would give me a view of the city one last time.

The garage door began to lift upward and the morning light poured in like a rushing flood. The Blue Bird began to move forward. The guard with a shotgun entered a cage through the doors in the back of the bus. In the front of the bus stood another guard holding a shotgun right by the driver.

I still couldn’t believe my life would end this way. A year and a half ago on Thanksgiving day I proposed to my girlfriend Theresa. I sent a notification to a recruiting center stating my interest in joining the United States Marine Corps. Life for me was just getting started, or was I just feeling sorry for myself? In between thoughts I stared at all the happy people walking on the sidewalk, riding in their cars, and others going about in their daily lives, a freedom I’d taken for granted. As I watched, the free people squinted their eyes at the prison bus as we rode by, and I could almost hear their judgmental thoughts. I was glad we could only see them but they couldn’t see us.

As we rode through the city everything seemed to be moving fast. Everybody seemed to be in a rush. But as I sat by the window I simply enjoyed the view. Every building, person, car, or tree that we passed gave me delight.

The Blue Bird finally made its way onto Highway 37 South. I kept my eye on every green sign that we passed. The most memorable sign that I read that day said, “Now Leaving San Antonio City Limits.”

I wanted to cry. I felt like I was being kidnapped. Deep inside I was crying. This was not how I imagined myself entering the adult world. Boy, did I have the most painful emotional blues during my bus ride to prison. I realized then why this bus was famously dubbed by the convicts of old, “Blue Bird.”

Illustration by Sarah Schneider

Two Memoirs by Jose Garcia

Riding in the Car

I’m sitting on a bench in a prison dayroom underneath a blaring television set. My buddy Shadow says hi to me and sits down. We take our car and head out back into the world.

We get to talking about the old neighborhoods. We’re both from different towns, different places, but the ride we’re in has enough juice to pull our worlds together.

I see a young lady walking down the sidewalk. He mentions a girl he used to know. I go ahead and swing the car out that way to see if she’s around. On our way, we spot an old store that Shadow says the gang used to hang out at. We stop in. While we are there, we decide to grab a shot of coffee.

In prison, we don’t have access to things in our cells while we’re in the dayroom. But we have some good peeps in their cells on row one who can hook us up with a shot. Going up to the second or third floor might catch us a disciplinary case. So, cups of coffee in hand, we get back on the road.

It’s a nice day. Plenty of sunshine. The noise of the dayroom disappears. We talk about other girls. Other places. Other times. Family. Homeboys.

Soon enough, the ride ends, and so does our coffee. The CO yells, “In and out!” We roll our car to a stop in the dayroom and turn it back into a bench. We tap fists and promise to take the car out again. Tomorrow.

The next day Shadow gets moved. Nothing special. Moves happen.

I get back under the TV. Still noisy. I sit and look at the bench. I see it is just another rusted-out piece of junk here.

Restless

Late at night, I wake up. Restless. I hear the whirr of a small fan. I feel the hard metal bunk beneath me, right through my mashed down mattress. Since my bed doubles as me and my cellie’s locker, the thought crosses my mind to get something out of it to munch on.

But no. My cellie, who sleeps on a bunk about 20 inches or so above my head, is sleeping. Not cool to make noise when the lights are off. He might think a mouse got in the house.

So I stay quieter than a mouse. I look at the metal table beside me. Nasty thing. The paint is chipped and it has rust flaking off. I sigh softly.

I would turn my radio on but it’s not working. It will take a couple of months to get a new one. Prison bureaucracies are amazingly effective, if vindictively so.

I could try to work on it to repair it but technically that’s not allowed. But. Maybe I’ll try. Or get a prison “radio” guy to work on it.

Cellie snores softly. I figure he is asleep. Unless, of course, he’s playing opossum. Like me.

The darkness is oppressive in prison. Even an innocent would feel this. The guilty get used to it. And after awhile, I imagine we all are, one way or another.

My cell door makes a loud click noise. The door rolls open. The CO yells in, “You ready for insulin!” I whisper, “Ayuh,” and get up. I take my clothes, cup, and toothbrush with me.

My cellie sleeps.

Back cover of ‘The Pen-City Writers’ by Alfredo Arizmendi

“In God’s Time” by Kevin Murphy

I open my Bible, something I do every time I get locked up. This is the same Bible that has sat on my shelf at home for years without being opened. It is like God and jail are connected somehow, at least for me. I open it now, not to seek God but to try and find a reason why I am here behind these walls again. As I read I come across a scripture that says, “The sins of the fathers are passed down to the sons to the third and fourth generations.” I like this scripture because it allows me to blame someone else for my being here again and who better than the man who was never there for me. I tell myself that I am being punished for my father’s sins, his unbelief, for his absence in my life, and I actually believe it. I go on like this for over a year.

During this time I am sentenced and sent to prison. On the unit I am placed on a section with a bunch of Christians and one of them is named Chad and he is on fire for God.

He starts working on me and I tell him what I believe about my father and he starts putting holes in my beliefs and shows me things that up till now I have refused to see. He opens my eyes to the truth and that night I go into my cell and I give my life to God.

Soon after I do this I have a dream. In my dream there is a table and on the table there is a thick file. I don’t know how but I know that this file is my case file. On the file is a hand and this is all I see, the rest of the room being filled with a bright light. Then I hear a voice and it says to me, “You are going to beat your case, you are going to go home.” I wake up so moved that I get a pen and paper and I write down all that I had seen and heard in my dream.

Three days after my dream I am sitting in the dayroom and a guard comes in and calls out my name. I answer him and he tells me, “Pack up your property, you are on the chain.” “Chain,” I say. I figure it must be a medical chain and I know I can refuse them so I say, “I’m not going, tell medical I refuse.” He says, “OK,” and leaves. It isn’t long before he is back though and tells me, “It isn’t medical chain. It is regular chain and you can’t refuse so go pack up.” I pack up my property and in the morning I am on the chain bus leaving the Connally Unit.

Three days later I am standing in an old gym inside the Walls Unit, wearing a white jumpsuit, eating a bologna sandwich, and watching the pigeons fly around overhead. It isn’t long before one of the guards comes in and starts calling out names from a clipboard he has.

I see that as he calls out the names the men are going over to him and showing their IDs and then he is writing something on their shirt fronts with a marker and telling them to go get in one of the cages on the other half of the gym. When my name is called I do like the others and he writes on the left front of my jumpsuit. I look down and I see cell numbers and below them is a cross. I ask the guard, “What is the cross for?” He says, “That is not a cross. It is an X.” I look again and it sure looks like a cross to me but I am not going to argue with him so I ask, “Well what is the X for?”

And he says, “Transit parole. You will be out of here by 6 AM tomorrow.” I can’t believe what I just heard so I ask him, “Excuse me?” He says, “What?” and I say “Did you say parole?” He says, “Yeah, aren’t you expecting to be released?” “Oh yeah,” I say, “Just not this early.”

“Well, they must have brought you up early,” he says. “Yeah,” I say and walk over to the cages with everyone else. Once inside the cage I sink down to the floor. My mind is going a hundred miles an hour. My first thoughts are that if they let me go I am going to run. Get some tennis shoes, hop in a taxi, and get as close to the water as I can so I can get on a boat. I have to get out of Texas and then go from there. Run, run, run is all I can think of.

From the cages we are taken to our cells. On the way I am in a daze. I can’t believe they are making a mistake and releasing me after only doing a year and a half on a life sentence. I have heard of them making mistakes like this before but I never thought it would happen to me.

I get to my cell and soon after I get a cellie. He asks me what I am doing here and I say, as relaxed as I can, “I made parole; I’m going home.” He says, “That’s awesome,” and I say, “You have no idea.”

The rest of that day I lay in my bunk plotting, figuring.

How much money do I have on my account? How far will that get me in a taxi from here? I figure that if I can get to Houston I can probably hide out there for a few days if I have to. As I am thinking on all of this, my dream comes to mind and I stop and say a silent prayer to God, thanking Him for letting me go. I feel ashamed that I didn’t do so as soon as I found out I was being released. I was just so caught up in the idea of getting out that I didn’t think of the why or the how.

That night they come around with fingerprint cards for everyone getting out in the morning. I don’t get one and, while I don’t want to bring attention to myself, I ask the guard passing them out why I didn’t get one and he says he will check.

He comes back and tells me that I am on the roster to be released but not until the first of the year and explains to me how the chain buses stop running during the holidays so anyone being released around the first of the year is brought here a little early. He tells me to relax and that I will be out of here before I know it. It is the 22nd of December.

Christmas comes and goes and I try to stay unnoticed. I spend my time planning and plotting and waiting for the year to end and the new one to come. As the new year approaches I am lying in my bunk, thinking about where I will go. I think that maybe Montana would be good or maybe Colorado, somewhere where I can get lost. I then start thinking about my son and how I will get him to wherever I end up and all of a sudden I know that I am not going to be released. It is like a veil is lifted and everything becomes clear. God isn’t going to let me go like this. This is not right. This isn’t beating my case.

And most importantly, my son isn’t going to be with me if I get out like this. I can see that God is just showing me that He can open doors that can’t be opened, that with Him anything is possible.

My heart is so heavy. I want out of here so bad and I was so close and now that I see that I am not going to get out of here I am hurt bad, I am devastated. I get down on my knees crying and I pray to God. I tell Him that I want to go home. I want to raise my son. I want to be with my family.

I tell Him I want all of this so bad but that I know that He isn’t going to release me, not now, not like this. I tell Him that I understand and that my life is His and that I am ready to go back and do whatever it is He is calling me to do. I tell Him I am ready to go back.

Three days later I am told to pack my property, that I am on the chain, and three days after that I am back on the Connally Unit.

Soon after my return I am asked to be a part of a group of Christians called Yokefellows and through that I am allowed to be a part of the first faith-based section on the unit. Then I am asked to be a facilitator in the second one. I have been a part of Kairos, both as a candidate in one of the walks and as a steward in another. I have taken more Christian-based classes than I can count and have taught and helped teach many others. I am very actively involved in the Catholic community and have been in several retreats and have stood with several men at their confirmations. I am also a part of the choir and I help with and set up the weekly mass. I serve God and have for the whole time I have been here.

It has been nine years. I don’t know when I am going home, only that I am and that it will be when He says I’m ready. It will be in God’s time, not mine.

An east Texas native, Kevin Murphy, AKA. Cricket, is a big ol’ country boy finding his way through the John B. Connally Unit where he has spent nearly ten years. He continues the fight to be heard and to return to his family.

Jason Gallegos obtained a GED, barber certification, and is currently taking a college course through the mail to earn a Bachelor’s in Divinity. As a hobby he piddles in the craftshop at the John B. Connally Unit, making leather items.

Jose Maria Garcia, Jr. was born on the third floor of Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center in Fort Hood, Texas. Traveling with the itinerary of an army brat, he has sojourned the warm climes of Panama and the frigid havens of Germany and South Dakota. He currently lives in Kennedy, Texas.

Correction 3/3/2017: An earlier version of this article’s headline implied these stories were fiction. They are actually memoir.

More

From VICE

-

Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic/Getty Images -

Screenshot: Marvel Rivals/YouTube -

Screenshot: DaFaq?Boom!/YouTube -

Paul Bergen/Redferns/Getty Images