All photos by Matt Williams

At the nadir of a long life rife with hard livin’, Margo Price found herself on a stiff bed in a cold room at the Davidson County jail for three days after a night of hard drinking. She had been spiraling into self-destruction since the death of her son Ezra in 2010, lost to a heart ailment just two weeks after he and his twin brother Judah were born. By some miracle, the spectacularly rough late night in Nashville that landed her behind bars resulted in only a single misdemeanor.

Videos by VICE

Price doesn’t like to talk about that night very much, partly out of concern for her family back home in small town Aledo, Illinois which, like all small towns, is prone to gossip. But it granted her the revelation that without righting course, this was only the beginning of how bad it might get. “At that point, I was feeling really depressed and I kinda thought about checking myself into an insane asylum,” Price says over a couple fingers of white tequila. “I was like, ‘I don’t feel good. Nothing’s going to make me feel better. Nothing that anybody does or says will ever make things fine.’ I was very angry at God. Just not happy with life at all. And then that was the answer: ‘Alright, well now you’re in jail, so…’”

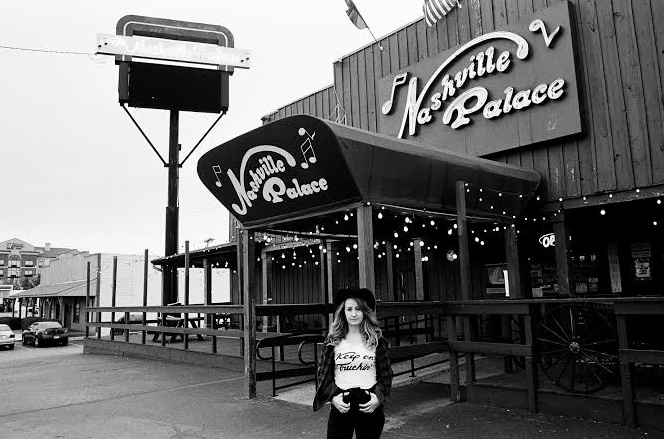

It’s a humid Tennessee afternoon. We’re sitting at The Nashville Palace, a stone’s throw from the Grand Ole Opry where Price first played just a few weeks ago, armed with songs from her fantastic upcoming album, Midwest Farmer’s Daughter. The Palace walls are lined with head shots of country music superstars and neon beer lights, stationed over old, dark wood. There’s a man sitting on stage by himself with an acoustic guitar that’s seen better days, pulling out classics and tunes based on the home states of the sparse audience. He’s an old pro, but it’s loud. Price gives a friendly and familiar hello to the bartender and asks something about her mother’s jacket, and we’re escorted to a small table in the empty and dim-lit backroom.

“It was great,” Price says about her Opry debut. “A rollercoaster. My mom came, my dad came, my sisters came down. My mother bawled for three hours straight—before, during and after the show—‘cause she was so happy. Then we came back here and we all partied, and I got up on stage at the Palace and sang with the house band.”

It was a long time coming to stand on that beat up old circle of wood center stage at the Opry. A big, black cowboy hat sits on top of Price’s head, complementing her Nashville-requisite cowboy boots. Her T-shirt, though, makes a bigger statement than either: “Keep On Truckin’.” It’d be hard to find a more perfect mantra to define her life. After more than a decade of grind, slugging it out over brutal tours in shithole clubs just trying to survive, to the outside world it might seem she’s suddenly an overnight success. But listening to the stories—true, personal stories—on her new record, reveals the whole picture. Price is a special breed of underdog.

Her mother was a teacher and her father lost the family corn-and-soybean farm they had in Buffalo Prairie, Illinois, eventually turning to prison work to support their family. She grew up in Aledo, a town of just 3,640 people known for its annual Rhubarb Festival. There, Price spent her graduation money on guitars, despite her parents urging to buy a more practical computer. She went to Northern Illinois University on a cheerleading scholarship to study communications, then dance and theatre and Spanish, but dropped out when she felt she didn’t fit in. When I ask if there was a specific moment that brought her to the realization school wasn’t for her anymore, she pauses and says, “uhh… When I ate mushrooms?” and laughs. I can’t tell if she’s joking or not.

In 2003 she moved to Nashville, where her great-uncle Bobby Fischer wrote songs for legends like George Jones and Reba McEntire, and formed Buffalo Clover—a gritty, rock ’n’ soul group she would play in for over a decade—with future husband Jeremy Ivey. They sold all of their possessions every time they had to find the money to make a record. They moved from town to town, even spending a chunk of time living in a campground in Colorado and busking for dinner money. They sold their Toyota Camry for a 1986 Winnebago they toured all over the country until it broke down. She played drums at SXSW while she was seven months pregnant with the twins.

After sinking into a “really dark depression” and entering “survival mode” after Ezra’s death, Price was trying her hardest to be a functioning human being, a good wife, and a good mother. She thought a return to music would be the best thing for her. But a harsh, zig-zagging tour sleeping on floors and playing barroom gigs for next to nothing broke her down again, inspiring the oddly jaunty but deeply blue “Desperate and Depressed.” The song references Richard Manuel, the pianist and occasional lead singer of The Band, with Price “thinking [she] might have his luck.” Manuel hanged himself in a Florida motel room after a gig in 1986. I wonder aloud what the reason could possibly be that she’s sitting across from me now.

“Probably just insanity,” Price says. “It’s like, why do you keep going? And I keep asking myself that. ‘Why are you doing this? You’re not making any money. You’re losing money. You’re spending a lot of time away from home.’ But there’s something in your brain that tells you to keep doing it. And if there was a switch, I probably would’ve turned it off a long time ago—the drive to make art, and to be creative, and to write songs.”

It’s a good thing for country music that switch is stuck, or more likely broken in position. Midwest Farmer’s Daughter positions Price as one of the most exciting voices in a reinvigoration of outlaw country that’s so far included people like cosmic cowboy Sturgill Simpson and Grammy Award-winning mountain man Chris Stapleton. The first true country album on Third Man Records, cut after hours at Memphis’s legendary Sun Studios, it begins with “Hands Of Time,” a poignant, devastating telling of Price’s life story, mixing sweeping strings with a classic country groove. “Tennessee Song,” with its thunderous chorus and dirty electric guitar, is a testament to the state that has always drawn her back. “Since You Put Me Down” takes profound heartbreak and drowns it in liquor: “I killed the angel on my shoulder with a bottle of the Bulleit / So I wouldn’t have to hear him bitch and moan, moan, moan.”

Price has all the rough-and-tumble twang muscle of outlaws like Waylon Jennings and Merle Haggard, and channels the incomparable Loretta Lynn throughout—the album title itself even alludes to Lynn’s Coal Miner’s Daughter—but never once feels like an imitator, backing up fiercely original lyrics with a story you couldn’t make up if you tried. In an era where authenticity is hard to come by and often murky at best, it’s tough to find a truer voice than Margo Price. Which is why that voice will knock the wind out of anyone in earshot when she closes the curtains with “World’s Greatest Loser.”

Getting it done was just as difficult as it had always been. She had to quit Buffalo Clover, which meant the emotional trial of firing friends she’d played with for years. She ended up pawning her wedding ring—which is now back on her finger—among other things. “My husband was gonna sell the car, and I tried to talk him out of it because it seemed like such an irresponsible thing to do, again,” Price says. “But I’m so glad that he did. I’d been wanting, for two or three years, to make a country record. To just get the songs out that we had.” They also sold a reel-to-reel to Brittany Howard of Alabama Shakes, who used it to record her gritty rock ’n’ roll project Thunderbitch’s debut record. And after all that, her album finally got finished. But then no one wanted it, or at least not the way Price wanted to put it out.

“I was still getting so many people who were like, ‘We’re gonna pass on it’ or ‘It’s too twangy’ or ‘We like it, but we wanna change this and maybe have you record a couple new songs.’ I just kept thinking that no matter what I did, I was always gonna fail, you know? That kinda like, born to lose, lowlife blood mentality. I just thought, ‘I’m gonna end up like Karen Dalton or Van Gogh or something.’ The rejection letters were getting super hard.”

There was one letter Price remembers that particularly stung. “It was just like, ‘Yeah, we’re aware of Margo. We’re just not hearing it.’ And that rejection was the one that broke my back that day. I remember going out to the liquor store and getting a bottle of mezcal tequila around four o’clock, and just not stopping until it was gone. Then I woke up the next day and was like, ‘Alright, can’t handle rejection like this, just keep going.’”

Shortly after, a friend walked up to Price at a bar and told her she was on Third Man’s radar, and Jack White was into what she was doing. She could hardly believe it. Worried about whether she could take another rejection, she sent them the record anyway, met with the label and fell in love with it. Third Man, she says, is full of “quirky and insanely creative” people, a far cry from Music Row and the sterile environments she’d been courting. “I’d been to a couple major label places and I’m just not used to that kind of setting at all—to go in and play for some women who are dripping in a bunch of gold jewelry and they’re like, ‘Oh, you’re not a hillbilly and you sing real country music! That’s so cute!’ It was like, do I need less teeth?”

I ask what she thinks might’ve happened if Third Man hadn’t picked the album up. It’s “a dark thought,” she says, but it wouldn’t have signaled the end of her songwriting. She might’ve focused on writing a book, or photography, or teaching dance. “I’d still be creating things, for sure,” Price assures me. “And even after this, you never know how long your shelf life as an artist is gonna be. At least I can say now I played the Opry.”

But those are all different realities in different universes, ones where Price isn’t on her way to crossing off the bucket list of venues she wrote down 12 years ago when she first came to Nashville. With the Opry and The Late Show conquered, the next logical one—if there’s any justice in the universe we’re living in—is Music City’s storied Ryman Auditorium. “Until I complete that list, I have to keep going,” she says. Whether it’s going to take a dangerous, white-knuckled trip back to the edge, to insanity, we’ll have to wait to see, but it seems as though those days are behind her.

Near the end of our conversation, Price mentions a song she’s excited to record named “Wild Women” that touches on the double standards between men and women in the music industry. “I’ve had a couple interviews where people are like, ‘So what do you do with your kid when you’re on the road?’ I’m like, ‘Do you ask Chris Stapleton that? Do you ask Sturgill? They both have kids.’” She says the song is about the judgement-free acceptance men enjoy on the road, and fiercely admonishes those who would make her feel like a bad mother, working to pay the bills and teaching her son not to give up on a dream.

Then, just before heading out into the torrential rain that’s begun to blanket Nashville while we’ve been sitting in this desolate barroom, Price issues the understatement of the century.

“I can hang with the guys,” she says. “Just as tough, I swear.”

Matt Williams wishes he were as tough as Margo Price. Follow him on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Ubisoft -

-

Tibrina Hobson/WireImage/Getty Images -

Amy and Stephen Allwine on their wedding day. Years later, Stephen went on to arrange the murder of his wife (Photo: Your Tribute)