In June, a report from Public Health England confirmed what many had feared. Black and Asian people are more likely to die of coronavirus than white ethnic groups, with those of Bangladeshi ethnicity at twice the risk of white Britons. It followed similarly damning research from the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre, which found that 14 percent of the most serious coronavirus hospital patients it surveyed were Black.

Clearly – and despite the claims of politicians and celebrities – coronavirus is not the great equaliser. The pandemic has not only revealed existing racial inequalities in our society, but made them worse.

Videos by VICE

Riaz Phillips, a London-based writer and photographer, read the Public Health England report and knew he had to do something. He remembered a recent New York Times article about the resurgence of community cookbooks during lockdown. As we search for ways to connect with people from afar – and spend more time than ever before in our kitchens – swapping recipes with people in our communities is suddenly a lot more appetising than using those of a manicured foodie influencer. Phillips decided to create and sell his own community cookbook, with all proceeds going to the Majonzi Fund, to support members of the BAME community who have lost loved ones to coronavirus.

This isn’t Phillips’ first foray into publishing. In 2016 he published Belly Full, an acclaimed book that documented Britain’s Caribbean eateries. For his latest publication, using his contacts in both the food and creative worlds, he fired off messages to BAME chefs, bakers, supper club founders, restaurant owners and food writers. The request was simple: send your favourite comfort food recipe. There were no rules about the type of dish or cuisine, no substitution of ingredients. Phillips wanted to publish his contributors’ recipes in exactly the way they cooked them.

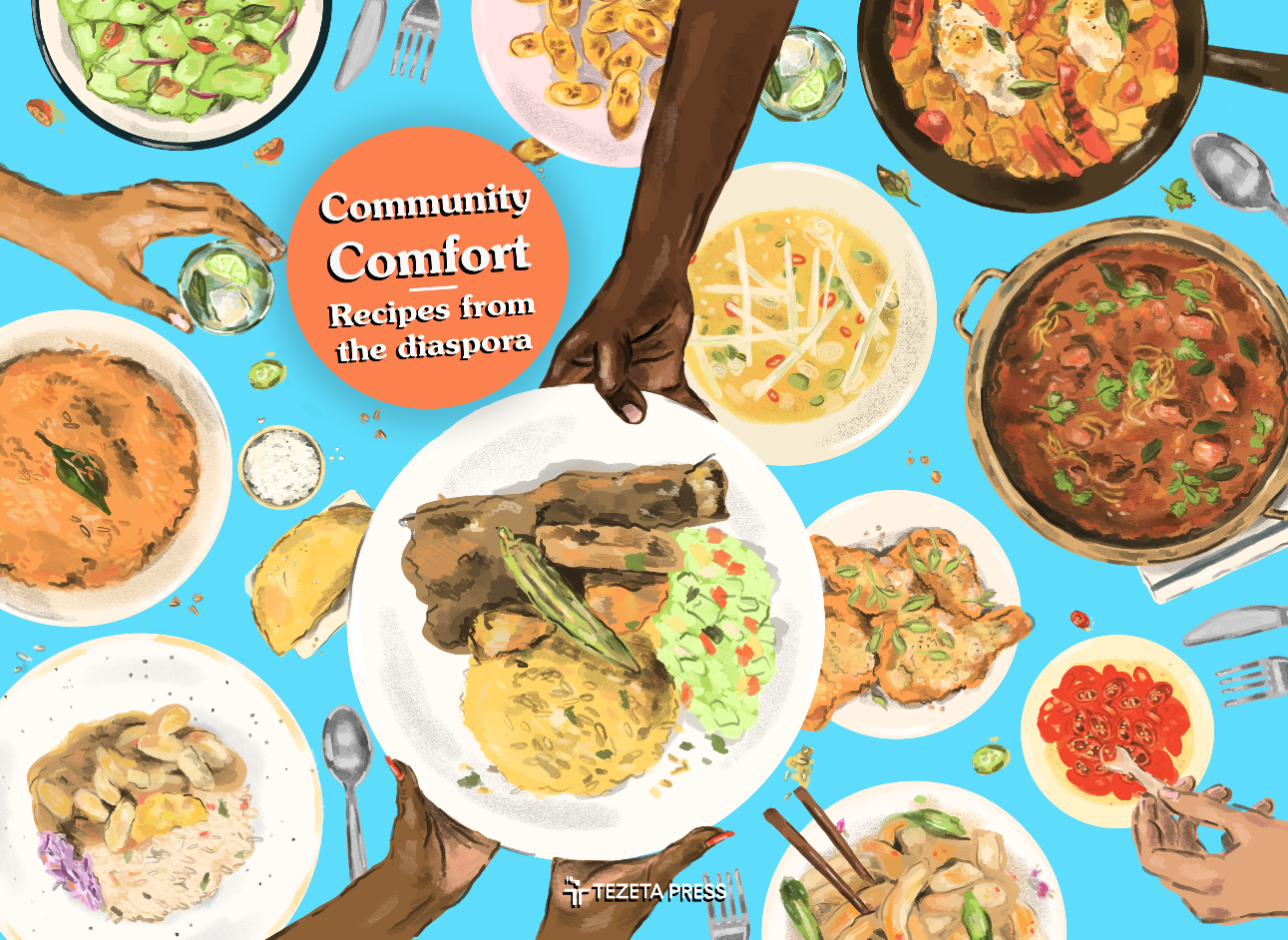

Last week, Phillips published Community Comfort: Recipes from the Diaspora. Illustrated by Javie Huxley, the e-book contains 100 recipes by British cooks from migrant backgrounds, including Ruby Tandoh, Denai Moore, Jeremy Chan of Ikoyi, Island Social Club’s Joseph Pilgrim, Emeka Frederick of Nigerian tapas restaurant Chuku’s, Longthroat Memoirs author Yemisi Aribisala and Original Flava.

The food is similarly wide-ranging, spanning empanadas, Kampalan red lentil dhal, plantain fritters, Brazilian pirão by Ottolenghi recipe developer Ixta Belfrage and a pav bhaji “Sloppy Joe” (think: fragrant, buttery curry served in a brioche bun) from chef Tanya Gohil. On its launch day, Community Comfort was downloaded over 600 times, raising nearly £10,000.

Just as the Majonzi Fund seeks to help those impacted by coronavirus deaths on a long-term basis, Phillips hopes that these recipes will stand the test of time. I gave him a call to find out more about how he made Community Comfort.

Hi Riaz. How did the idea for Community Comfort come about?

Riaz Phillips: It came about around the end of May, when the news started coming out about coronavirus and how it was having a bigger effect in some communities than others, particularly Black and Asian communities. That was a real downer at a time that was already quite down. Myself and people I talked to all felt a bit helpless. A lot of us were doing small stuff, but you feel kind of helpless about how to do something on a larger scale.

I’d also seen an article in the New York Times about community cookbooks. I thought it was really cool how they galvanised a small group to come together for a good cause. I thought about the food I’d been eating in lockdown, which was a lot of comfort food. From being on social media, I saw a lot of people were turning to comfort food cooking as much as the jazzy, show-off, Instagram-style stuff. I knew that, if I was turning to it and these people online were turning to it, it could be a benefit for others. It could be informed by all these different comfort foods from the diaspora. And that’s how it came along, really. I thought if it was helpful for us, it could be helpful for a lot of other people.

It’s a great idea. The idea of what “comfort food” is can change so much depending on who you are: what your background is, what foods you like. It’s a wide remit, but none of the recipes in the book are the same.

Yeah, they’ve got similar undertones, but I didn’t dictate to anyone what their recipe should be. I was actually prepared for some of them to be the same – it just so happens that none of them were identical.

As you said, it was interesting how comfort food means something to different people, and readers can get a different purpose out of the book. If they’re looking for nostalgia, they can get it; if they’re looking to get full up, they can get it; if they’re looking for a social activity, that’s there. But if they’re looking for an isolationist evening of cooking, it’s there too. Quick bites, long drawn out cooking – it’s all there.

At the same time, these are foods that are really pivotal within these communities. Outside of these communities, few people know about them. And that’s not just a Black or white thing, that’s like West African people not knowing empanadas, and likewise, Colombian people not knowing about jollof rice. So it’s trying to spur that cross conversation.

That definitely comes across in the book. There’s a section in each of the recipes where the author tells you about the dish, sometimes with the memories they have of it. Even if you’re not using the book to cook, it functions as a narrative on what diaspora cooking is.

A lot of the contributors sent the name of the recipe and, in brackets, put what it would otherwise be known as. I deleted most of them, actually – the English translations – because I was like, “If that’s what you call the dish, then that’s what people should know it as.” So it was cool to have everyone submit these recipes – a lot of them I’d never heard of before

It’s an impressive list – over 100 contributors. You only had the idea in May, you must have been sending out emails and DMs pretty fast.

I started with people I knew were on the same wave as me, so people who don’t really require a whole conversation – I just sent them the idea and they understood where I was coming from. And then I guess what helped with the time was that I designed it myself. So, as each recipe came in, I was able to put it into the document.

I shot a lot of the photos, but some of the photos were the ones that people sent. I didn’t actually want it to be all my photography. With the stories and the photos, I kind of wanted each recipe to represent the person who sent it – their style of writing and photography. For obvious reasons, I had to standardise some of the recipes – a lot of people use cups – but for the most part, I wanted to keep it as authentic to their style to get readers to know them.

It links to a conversation that is happening in the food world in conjunction with Black Lives Matter. Lots of food writers and recipe developers have spoken out on social media about experiences of writing recipes from their native culture, and sometimes they’d have white editors who would change the spelling of the dish, or even its ingredients, basically to whitewash their recipe and make it more palatable for a perceived white audience.

I don’t believe in any of that – I think that reader should be less lazy

Exactly, I feel like Community Comfort is the antithesis of that way of thinking. Were you working on the book at the same time as the first George Floyd protests?

It was before. People kind of think it was a result of that. It was before that, and would still have happened even if none of that stuff had happened. I’m quite adamant, like, “This news came out before all of that, and I was Black in May and I’m still going to be Black next year.” These things are still important to the Black community, and it’s the same for the Bangladeshi and Pakistani and Indian communities as well.

Do you have a favourite or stand-out recipe from the book?

There’s a lentil dhal and mushroom rice by a guy called Isreal Mbabazi, and that one I’ve made a few times already. He’s from East Africa, but because of the makeup of that location, it has a strong southeast Indian population, and that’s a legacy of colonial Britain. The recipe is a mix of East African and Indian heritage, and it tastes amazing. And then there’s an Indian take on a “Sloppy Joe” by Tanya Gohil, which is amazing – it’s basically a heap of vegetables, oiled, and then on a heavy-based pot is loads of spices and herbs and onions cooked down until they’re really soft.

That’s one of the undertones in a lot of the cooking in the book. It really demystifies a lot of the confusion around these foods. They appear convoluted, maybe because of how many ingredients they use, but they’re super simple and they last for ages.

And you’ve got a recipe in there, too: slow stew peas. Can you tell me about that one?

It’s basically what started it. I live in Peckham, and I was trying to find slow stew peas, but I couldn’t find it anywhere – which is mental, because it’s one of the most basic things that everyone usually serves. But because there’s no footfall, they stopped making it. It’s one of those things that’s quite predicated on footfall – you can’t really save it and use it the next day, in the commercial sense anyway.

So I asked my mum how she makes it, and she gave me a loose recipe for it that I tested over the week. When you go to Jamaica, it’s something that’s everywhere when you’re driving around; when you’re walking around in the markets; downtown; uptown; in the corner of shops and car garages – you can find it literally everywhere. It’s one of those things that’s part of everyday life. If you have a lunch break, you’ll go and queue up and get a cup of soup, and it’s super cheap – like a pound. The fact that hot soup is comfort food to people somewhere where it’s 40 degrees every day tells you how good it is.

What’s exciting about the stew is how it changes, and you never know what you’re going to get in your cup. Sometimes you might get loads of carrots and potatoes, and that’s actually a bit annoying. Sometimes you might get an extra bit of meat, sometimes you might ask for more spinners, which are the dumplings. Sometimes you might get hearty pieces of yam. No two bowls are ever the same.

I definitely want to make that. Am I right in thinking Sandra Phillips – who’s got a recipe in here for callaloo – is your mum?

Yeah, she’s my mum. It was important to have that representation of the everyday person. I don’t want it to all be master chefs and Michelin star people, just to have a nod to the fact that in these times we’re in, there are people at the front who get the limelight for doing all the work, but then there are people at the back in the trenches who are equally important. Also, it tied in with a lot of the other recipes, which usually have callaloo as a side.

Can you tell me a bit more about the Majonzi Fund?

The project isn’t officially tied to them, I’m just going to give the money to them. I picked them because, first of all, I hardly saw any campaigns or specific funds or any access to relief to these communities who were most affected by the coronavirus. The small things I did see were short-term, like food banks or instant funds. Majonzi were talking more about the long-term lingering effects of what we’re going through. A lot of the money they are using is mainly going to go on therapy and PTSD treatment for the family and friends of those who passed away. I thought that was quite interesting, because we’re kind of still in the pandemic – we can’t really see the outside of it and the full extent of what we’re going through. We’re still very much in the middle of it.

Majonzi also set up initiatives around the fund to help change the framing of mental health awareness in the Black and Asian communities, which is something that needs a lot of work. Some people don’t accept that they have mental health issues, or get them seen to. It’s a double whammy. So they’re looking at all these different sides of the backend of this trauma

They said they wanted to raise a certain amount, so I decided if they said that’s how much they needed, I’d raise the same so they’d have double what they need.

How much did they say they needed?

£50,000 was their target, and we have nearly £25,000 in nearly two days.

Wow, and it’s still ongoing. What has the reaction to the book been like from readers and contributors?

It’s been really good. People have been saying they never thought certain foods would be published in an English cookbook – like kele-nono, which is Yemisi Aribisala’s recipe from her own vivid imagination. Or pirão by Ixta Belfrage – that was one of her childhood snacks growing up in Brazil.

People have also been doing all kinds of combinations of different cooking. Someone sent me a photo the other day – they’d made jollof rice and Brian Danclair’s Trinidad curry chicken and Dr Rupy Aujla’s spinach and chickpea saag. They’d made this amazing dinner of three diverse recipes, and I thought that was amazing, just trying to foster this cross-communication.

The fund is aiming to be long-term – are you thinking in those terms with the book? Would you do a follow-up?

I think that’s the joy of social media – you can separate your own face from projects and they can live in eternity. So now that the Community Comfort page is there, it’s going to exist for as long as it’s up. Hopefully people will keep seeing it and buying it. It also means that we can gauge the reaction from people and see what they were interested in, and maybe do a new project off the back of that in the future. You know, you’ve built that community of people who care about those issues.

You’re creating a community by writing a cookbook all about community.

Yeah. The last thing that I tried to mention in the chapter leads is that a lot of the recipes aren’t that codified or rigid. They don’t have to be followed to the T. If you haven’t got all the spices or ingredients, that’s fine. A lot of these things were not made with the Western ideal of a recipe in mind. That’s for me as well. Cooking can sometimes be scary – especially when it’s a whole new food culture you’ve just been introduced to. It’s great to demystify it without dumbing it down.

The project’s aim was two-fold. It was to raise money for the cause, but the underlying thing that I hope to accomplish out of it was to spread the diversity of the people in the food scene – and not only for their heritage food, but to show that these people can cook and have amazing ideas in food that isn’t connected to their heritage, which doesn’t happen enough.

Interview has been edited for length and clarity.

To donate and download Community Comfort: Recipes from the Diaspora, visit the Tezeta Press website.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

Gerenme/Getty Images -

(Photo via South_agency / Getty Images) -

(Photo by Thomas Barwick / Getty Images)