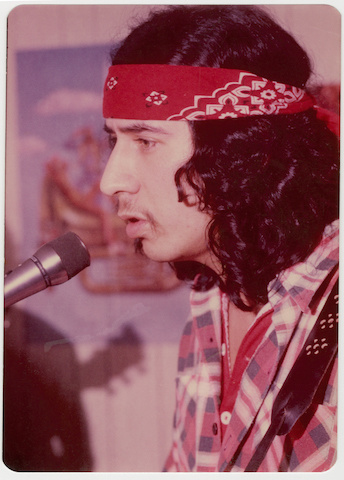

Willy Mitchell and Desert River Band, photo courtesy of artist.

“They watched him shootin’ at me. He missed me twice, and when I got to the tree line, he was on the edge of the road, at the snow bank. That’s where he fell, and the gun went off. But that was it — he took the gun out. He should never have taken that gun out.”

Videos by VICE

— Willy Mitchell

The liner notes of the compilation Native North America (Vol. 1): Aboriginal Folk, Rock & Country, 1966 – 1985, curated by Vancouver-based DJ, writer, and Canadian music historian Kevin “Sipreano” Howes and released late last year by Light In The Attic, are full of stories that beg digging deeper. Bonafide legends of Aboriginal Canadian music appear on the 3-LP set (Willie Dunn, Willie Thrasher, David Campbell, Morley Loon, Shingoose and Duke Redbird), and Mohawk/Algonquin singer-songwriter Willy Mitchell is definitely one of them, but his story is darker that anyone’s, hinging on events that precede his music career entirely. In Maniwaki, Quebec one night in 1969, a 15 year-old Mitchell became the unwitting accomplice to a prank his friends had pulled when they shoved a bunch of stolen Christmas lights into his arms. A police officer showed up moments later, at which point Mitchell dropped the lights and took off running. Accounts differ as to what happened next, but when the melee cleared, Mitchell was lying in the snow with a bullet in his head. He did recover in the hospital, and bought a guitar with the meager settlement he received afterwards, later writing about the experience in the song “Big Police Man,” but that still wasn’t the end of the story.

Willy Mitchell, photo courtesy of artist.

Noisey: I was reading about when you were born — I have family in Cornwall, and I know your mother was turned away from the hospital there and you ended up being born in New York. What happened that night?

Willy Mitchell: Well, she said that her and my late dad… well, my late mom, too — said that they went in there and it was almost midnight I think. It was at nighttime, and they didn’t see anybody around. Just the one doctor, and he was at the reception desk. He was talking and laughing with the nurses there, and when they went in, she told them, “I think my water’s going to break. I’m pretty sure I’m gonna give birth here.” And he says, “Well, why don’t you go to Malone? It’s only 40 miles. You can make it there. We’re too busy here.” She was surprised. My late dad said, “Come on — let’s get out of here.” So they took off, and I was almost born in the car. Her water broke in the car. They came out and they got her and they brought her in and I was born right away.

Did she feel they were discriminated against or that the hospital was lazy?

Yeah. They knew. They knew the Mohawks were right there. They always went there to give birth. It was close. Just across the bridge. But it was bad timing for my mom, I guess.

Well, with the oppression that Aboriginal people have faced over the years, it’s important to tell stories like that. Some of that comes out in the music, too, yeah?

Well, I never wrote about that! I always tried to stay away from that myself because I thought it wouldn’t help the situation by singing about it. And I kinda figured that the white people don’t wanna sit there and listen to that crap, either, about their people. I always wanted to sing about the animals and the land and our ceremonies. Spiritual things. The sun, the moon, the stars. The rainbow. Nice things, you know?

Were those practices alive — the elements of your heritage — when you were growing up and going to school?

On the res?

Yeah.

The elders weren’t practicing their ceremonies on our res, no. They were building canoes, though. Birchbark canoes. They still are. And making snowshoes. A late friend of mine, he was an ex-chief — Chief William Commanda — he was a friend of mine, and he was spiritual leader. A national spiritual leader and a good friend of… oh, what’s his name… the black leader in South Africa…

Nelson Mandela?

Mandela! Yeah, Nelson Mandela. I’ve seen a picture of them two together, laughing. They met a couple of times. Nelson Mandela really liked him. A very timid man. He liked to laugh and he was the carrier of the wampum belts. He used to travel and teach about the belts, what they stood for. He had two belts, and one was very, very old. He didn’t open that belt too often because it was falling apart. There’s another spiritual leader who received the belts and he’s going to be taking care of them until somebody is appointed to hold them. This belt is falling apart. There are symbols on it. There’s a cross on the right hand side, and there’s another symbol after that which stands for “white society.” And then there’s the symbol of the redman. The beads are falling off from the right, and the cross is half gone. The church is all locked today. There’s hardly anybody going to church anymore. I don’t know if that’s what it means…

How old is the belt?

Oh… 1500s I think. Or 1600s? It was made with wampum shell. I’ve seen it a couple of times. I listened to my friend talking about it. When I was in college, he came to the college and spoke to everybody, and he had the belts with him. He had his helper there — the man who’s holding the belts right now.

Did you know the chief already when he came and spoke at your school?

Oh I knew him since I was five years-old. When I got shot, I had to go to court about five times, and he was always there. He was the chief at the time, and he was always there in court, listening and listening. And at the last day, he spoke to the judge and everybody.

On your behalf.

Yeah. And all the Algonquins, I guess. It was nice, what he said. He made everybody think. And the judge — he just agreed that it was an awful thing that happened to me and for sure he didn’t do this on purpose. And that’s true. The man fell down. I believe. I didn’t see him fall, but I believe him. He passed away now, the police officer.

Did you have any sort of contact with him over the years? I know you wrote the song, “Big Police Man.”

No. I wanted to, though. He passed away about three years ago. Just after my late mom. And I… it was about the past 10 years I’ve been wanting to see him. I was never on the internet… well, neither was he, I don’t think. I wanted to see him in person and I never got the chance to go talk to him about it. But I’m good friends with one of his nieces, and she assured me that everything was cool and he was a good man. He adopted children. The kind of guy that held the door for people at the mall.

What do you think it was in the last 10 years that made you want to connect with him? Just time?

Well, I never really knew what happened that night. My friends were saying this and he was saying that he fell, and my friends were saying he didn’t fall. And that was the question every time we went to court — did he fall or didn’t fall? And we’d go back up there again in court and continue: “Did he fall or he didn’t fall?”

As in he fell and that’s how the gun went off?

Yeah. So I… I got mad at one point, and when I was on the stand, I yelled. I yelled in court. I looked at the judge and I said, “Why are you always talking about him falling and not falling? He got a telephone call that kids were stealing light bulbs. Kids! It wasn’t a bank job he was going to!” He comes there and as soon as I took off running, he had my two friends right there — he could have taken them. They stopped right there on the sidewalk. They watched him shootin’ at me. He missed me twice, and when I got to the tree line, he was on the edge of the road, at the snow bank. That’s where he fell, and the gun went off. But that was it — he took the gun out. He should never have taken that gun out. I spoke to many policemen. And judges, too. I spoke with lawyers about that. They all agreed. He wasn’t supposed to touch that gun. So why did I only get five hundred dollars for that? To this day! So I bought a guitar and I wrote a song about it.

And then you played it on television the first chance you got!

Yeah! With a professional band. I wish I could find that tape.

It’ll probably pop up at some point, the internet being what it is.

I went in there personally, to the studio. The reception guy there just looked me up and down and said, “Well, we don’t have any personnel to work on that in the archives.” It was probably in there somewhere, but there’s a lot of stuff and it’s gonna take a while to find that.

A lot of digging.

And he didn’t have the staff to do that.

Was there any kind of reaction when you went on television and played that song, with that message in it?

No, not really. It just made people talk for a while, I guess. There was singers from each town, from Maniwaki to Ottawa, maybe about five towns. And there were singers from each town representing their town. And I was representing Maniwaki at the time.

That’s an important story for that town.

They’re trying hard to hide it.

I bet!

Oh yeah. I tried to find something on it, and I couldn’t find nothing. Nothing on the internet. Nope. They even had a yearly historical calendar of events that happened, like the big flood in ’68. They had every natural disaster — earthquakes, tornadoes. They even had a plague. Typhoid fever. Two people died there.

But nothing about the officer shooting you in the head.

In 1969, “nothing happened.”

They don’t have the personnel to look that up I guess.

The people remember that for sure. My brothers and my cousins, they went to town with guns and they closed the street. They took over a bar and they had hostages there. But the hostages were old white men, and they were with us! They didn’t wanna go. They were mad at the police, too.

That was in protest to what had happened to you, that they took over the bar?

Yeah. There was about 10 guys there with .30-30s and the police had barricades on both ends of the street and there was police on the roof. And the chief of police came to the bar there and he showed his hands and he said, “I’m unarmed. I wanna come in and talk to you.” So they let him in, and he told them, “Nobody’s gonna be charged for this. You can keep your guns and nobody will be charged. There’s no one out takin’ license plates or nothing. You can just go home. That’s all we want. We’re sorry this happened.” And so everybody went home. The old men were clapping and yelling.

How soon after you got shot was that?

I was in the hospital when they did that. It happened at night, at about 10 o’clock. The next day, the radio was even saying that I was shot and killed. So they closed the high school in town. They had about 400 students there and they all had to go home. They were worried that something was going to happen. My late mom was coming up from New York. The priest from the res called my mom because they were AA friends. He was an alcoholic priest — they used to go to AA together. So he called my mom and didn’t wanna tell her that I got shot. He told her that I fell off the stage and I hurt myself a little bit, “But he’s going to be okay.” He was in the hospital in Ottawa. So while they were coming up, they were somewhere close to Ottawa, and the radio was on, and my two brothers were there. And the guy on the radio said, “A 15 year-old Algonquin boy was shot and killed last night — Willy Mitchell.” And my mom just almost fainted. She almost went in the ditch, and my brother had to drive and they managed to stop the car and she couldn’t breathe. It was a heavy report for her.

And your brothers didn’t know any different. They didn’t know you were okay.

No, they didn’t know either. So they came straight to the hospital. I remember I was in intensive care and my older brother, he was looking down at me and I told him, “Don’t worry. No little bullet’s gonna put me down.”

They were showing up expecting to find you dead.

Yeah. Then some reporters came… I forget the name of that program. It used to be on once a week… something like W5 or something. Very special documentary reporting. They wanted to do an interview with me, and they snuck a camera in the hospital. There was a big box, and it was wrapped like a present. A bow and everything. They put it on my table, you know where you eat, on the table? And they had that in front of me, and on the side of the box, he just flipped the two flaps down — one for the lens and one for the controls on the side. It was all set. And we were just about to start, and the doctor came in and he recognized them because they had already asked him if they could do an interview, and he said, “No, it’s against regulations.” They snuck in anyway, and the doctor was upset about that. He said, “I told you, you can’t do this here. He’s leaving today anyway.” This was three weeks later — that’s when they came in. They happened to come in on the day that I was leaving. I didn’t even know myself I was leaving. And the journalist, this woman — very beautiful woman — she told me, “The RCNP are waiting outside for you. We’re gonna have to sneak you out. I think they still wanna charge you for stealing those light bulbs.”

Good lord.

Yeah! And she said it wasn’t the light bulb thing. They just didn’t want the media to get to me and blow this up and all that.

And did they intercept you?

She told me just put my arm around her and walk out with her like that and pretend we’re lovers.

Which was fine by you, right?

Oh yeah! [laughs]

So after that is when you bought the guitar and started really writing?

Yeah.

When did you go away to Manitou Community College?

Oh, that was in ’73. The building used to be an American anti-missile base that became obsolete. It was equipped with a gymnasium, a cafeteria, recreation, two bars, heating plant, a hundred and fifty houses, maybe a little more. Clusters of houses. They gave it all to Indian Affairs, and Indian Affairs gave it to us. I went there only to work in carpentry and stuff. I never knew I was actually going to be attending classes there. But it was all operated by Native people, and I met Native people that I’d never heard of before. Mi’kmaq, Delaware… I only knew Crees and Blackfoot, stuff like that. I didn’t travel much up to that point.

What kind of things were you learning there?

Medicinal Botany. Plant medicine. We had traditional arts where some of the students made cradle boards, and some of us were tanning moose hide. They had elders come in and teach us these things. And we got credits through this from Boston College in Montreal. We were accredited through there. They had a very good photography course. Black and white developing, and audio visuals — we made a 16 milimeter film, with the help of the National Film Board Academy. It was part of our course. And we had sports, too — hockey, basketball, volleyball, badminton. All equipped with weights. We were lifting weights and we had a trampoline in the gym. It was very nice there. For four and a half years it lasted, and some of the chiefs of Quebec were complaining that this place was costing too much. It was taking away from the individual communities, and they wanted it closed. The students were mad. They had the National Guard on standby, just outside of town. They had some trucks there, and they were waitin’ to come in in case there’s trouble. But it was all peaceful.

That was a significant time for you to be in college. 1973 was Wounded Knee.

Oh yeah, everybody was wearing headbands and really into that, too.

Did you hear a lot about that at the school?

People were reading books about it. There was a couple on it out about the history of what went down in the past, like in the time of Abraham Lincoln, when he hung those 350 Sioux. People were getting riled up about things like that. And the black thing was happening, too. It was the tail end of The Civil Rights Movement. It was a tense time. A lot of people got shot. Presidents, Senators…

Things were boiling.

The tea was boiling.

“Call Of The Moose” is in part about a parade of decorated moose heads mounted on cars and then driven to the city dump. Is that something that was common?

I started writing that right before I went into college. I wasn’t really singing about one thing in there. It was just a “leave the animals alone” kind of thing. Because I was watching moose gettin’ slaughtered every year, thousands of them across Quebec. Seven, eight thousand moose a year. If it keeps going like that, there’s gonna be no more moose. I feel that the government wants it like that because there’s a lot of accidents on the highway with moose, so they prefer not to have them around. It’s only the Indians eat that, anyway, now that I think about it.

So whose practice was that? That parade. Were those French folks? This wasn’t an Aboriginal thing.

No, that was the French people. Totally French. It’s a French town, Val-d’Or. We were living there at the time. And we used to watch that every year. We lived close to downtown. You just look out the window and you see them going by. People drunk, Christmas lights in the eyes, or bottle caps. Big eyes and sunglasses, hats on the moose head. They put hats on the head and try and make it funny, and they’re just laughing at the moose. To us, it’s our buffalo. We’ve lived off moose for centuries, using everything. I wanted to make a video, actually, of that parade. We were gonna get a pig’s head and put it on our car, put bottle caps in the eyes. And I was gonna stand on top of the car with my guitar and join the parade and just kick that pig’s head and jump down and just pretend I’m jamming, you know? But we were young and dumb. We would have been disrespecting the pig. After the parade, we went to the dump just to see, and holy man almost all those cars were at the dump, and they were throwing their moose heads down the hill into the garbage. You could see the moose heads just tumbling down, falling in the garbage. And we eat the moose head, too! There’s a lot of meat in there. There’s the tongue, there’s the nose, too that’s really good. But these people never eat that. They only want the head. A lot of them leave the whole body in the bush.

So they were just slaughtering them. They weren’t even using them.

No. Just slaughtering them. “Oh, I shot a moose! I’m gonna put it on my car.” I stole one, one time.

Off a car?

Yeah, I stole a moose head. My oldest son was about three years-old, I think, and we were still living downtown. I was lookin’ out the window and I seen a car with a moose head on it, waitin’ at the light. He had his signal on, and he was going to turn and go downtown there, just around the corner. I looked, and I could see blood dripping down the fender, so I knew that was fresh! And we were havin’ a hard time at the time. My wife and me — she had just started work, and I couldn’t find a job right away when we moved there, so we ended up on welfare. We were struggling. So I told my son, “Get dressed! We’re gonna go downtown.” And he put on his coat there and I helped him and I got a knife and we went downtown, and I seen that car parked right in front of a restaurant, right where I thought it would be. I went and looked in the window and I seen that guy sittin’ there. I could tell he was gonna eat, and he had a moose here. So he’s parked facing the sidewalk. They don’t park parallel with the sidewalk. Anyway I was lookin’ around for people and there wasn’t hardly anybody so I went over and I started cuttin’ the ropes and my little boy was askin’ me, “Is that Daddy’s moose?” “Yeah, yes.” So I picked it up and put it on my shoulder and I started walkin’ away with it and my little boy stayed there. He’s just lookin’ at the car, all the ropes there. I said, “Come on! Come on!” I told him in Cree, “Hurry up!” I had to go back and get his hand, and I’m holding this moose head on my left shoulder and I’ve got him by the hand and quickly went around the corner and went upstairs to the apartment. And we had a boarder, a friend of mine who had just moved to Val-d’Or, and he started work where my wife was working. He came home for lunch and he seen the moose head there. I had already started cutting it up. I was making soup. And he enjoyed the soup and everything. And he went back to work, and when he came back after work, he was laughing when he came in the house. He said, “You’ll never guess what happened.” He said, “One of our secretaries, I heard her talkin’, and she says, ‘You know what happened to my husband? He went in the restaurant this morning, and when he came out, his moose head was gone!’” He started laughing, my friend, because he knew. That woman said, “There’s some crazy people in this town,” she says.

But he didn’t tell!

No, he never said a word. It’s a small town, but it’s big, too.

Is a soup a usual thing for a moose head?

Oh any part… any part of it. Like around the jaws, around the jaw area, there’s a lot of meat there.

And how do you prepare the rest of it?

Well, moose nose, you put it on a stick and you burn it a little bit, you know, all the hair off. And then you’re cleaning it while you burn it. And then you cook it like that, right on the fire. The tongue, you cook it like what you would do with a cow’s tongue. There’s a lot of good meat in there, too.

Put it in foil on a fire?

Yeah, or you boil it. Usually we would boil it. We eat the intenstines, too. First we have to get a bunch of evergreen branches, and then we make a fire and you put those — you gotta make smoke, yeah? Create a lot of smoke. You can put those intestines on top of them branches and they get smoked. And then you turn them inside out and you just wash them and smoke them some more. They’re good. We do that with bear, too. Bear intestines. I’m not too fussy about it myself. I eat it, but it’s kind of rubbery for me.

So are you actively making music now, are you writing new songs because of the attention that has come with this compilation?

Actually, I have 10 or 12 new songs that I’ve been writing… since 1993 I guess I’ve been working on these songs. Some of them are not finished, and I guess some are. It seems like when I get to the studio, that’s when my wheels start turning. I wrote a song from scratch in about a half hour on my second to last album. I called it “Ceremonies.” That song was about a canoe builder. It was about my friend Chief William Commanda. He never went to school. Never went to school at all. I heard him telling people that one day. He says, “But I made over 40 birchbark canoes and I made over 400 pair of snowshoes.” He had these monster hands, this guy. He used the carving knife a lot. My other friend who passed away, too — he was one of my elders — he was a canoe builder, too. And his son is doing the canoe building today. He actually went to Tahiti a couple of years ago and built a canoe over there. He brought all of this bark and the roots and everything he needed. And he had all his expenses paid to go there and stay for I don’t know how many months — six months or so?

And show them how to build, huh?

He just wanted to show them how they do it. Because they don’t have bark down there or anything like that. They have dugouts. They actually gave him a dugout, but he couldn’t bring it back, so they said, “We’ll keep it here for you. If you ever come back, you got a canoe.”

Jeanne Poirier was a collaborator of yours?

Yeah. That was her that got the Sweet Grass Music going. I only helped here and there.

Is she still alive?

No, she passed away. It was really something how she passed away, too. She developed cancer, and she was always working on projects, typing out projects. For the Quebec Native Women’s Association or anybody else who needed writing or something. And she was making her own project for Quebec Native Women, and she managed to finish that project, and then her mom found her in bed. She passed out with her laptop on her lap. She finished it.

She did radio, too?

Yeah. We got a radio station going in Val-d’Or, at the same time when I was living there. That was the same time we did that record [“Call Of The Moose”]. That was recorded by the Rolling Stones’s old truck.

Their old mobile truck?

Yeah. Deep Purple brought that truck to Geneva, where they had that fire. Frank Zappa and Grand Funk Railroad and all them. A whole bunch of bands were there. They lost equipment because of that fire, and they ended up writing and recording “Smoke On The Water” in there, because it’s about that fire. And some French guys from Quebec bought it, and they charged us a thousand dollars an hour plus his expenses. He said he didn’t need a room. He had a berth in the truck. But they went straight back after the [Sweet Grass] festival. They came and set up for the festival and then went right back. So we only paid them $3,000 plus gas. He really liked it. He said, “I’ve recorded a lot of people, but this was something different.” He was in the truck watching the show and he had a video camera on stage. And he was watching us there, adjusting the sound.

Sweet Grass must have been a big thing for your career.

Oh yeah, just like that first television show I did. It gave me that kind of feeling. Something good happening here. If you listen to “Kill’n Your Mind,” there was something happening at the beginning. My bass player, he was a French guy, very good bass player. I told the guys, “I’m gonna go out alone. I’m gonna say a few words and I want you guys to come out and just pick up your guitars.” And when they came out, I kept looking at him, and he was looking backstage. He kept looking back. We were playing “Kill’n Your Mind,” and he’s looking back, and he’s got this worried look on his face. I took one look but I didn’t see anything. He was the only one who was able to see his wife on the floor — she fainted! Just as they were coming out. And he didn’t know what to do — keep playing or go tend to her. But then some people ran over and took care of her, and she was sitting up on the floor after that and she was okay.

She fainted from seeing him on stage?

Yeah, we had just come from visiting the truck. When we were in there, it was like we were in a spaceship or something. Blinking lights and reels — two, three inch reels. Regular reels. Shag rug and spotlights. And a 64-track console with captain chairs up there. You had to go up a few steps. And I was sitting in one of those chairs up there and somebody said, “Hey Willy, you know Ritchie Blackmore sat there a lot.” I said, “Oh yeah?” He said, “Oh yeah. Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, David Bowie, Sting. They all sat in these chairs.” So I said, “Well, if you see any of them, you tell ’em I sat here, too.”

Lance Scott Walker is a New York City-based writer. He is the author of the books Houston Rap and Houston Rap Tapes.

More

From VICE

-

-

NFL on Fox -

Screenshot: Genki -

Screenshot: YouTube/Meta Quest