They were unarmed, Ice Cube says. That’s what still bothers him. It’s the only thing that really felt different.

Mike Brown was unarmed when officer Darren Wilson shot him to death last August. Eric Garner was unarmed when officer Daniel Pantaleo put him in an apparent chokehold before Garner died at a hospital an hour later. It didn’t used to be this way.

Videos by VICE

“You used to have to have a gun to get shot, or a weapon, or a knife or something,” says O’shea Jackson, who has gone by the stage name of Ice Cube since his rap career began in the mid-1980s. “Now, the police are just executing people in the street. No weapon, even for a little altercation or a fist fight or whatever had gone down. They’re just gunning people down.”

Jackson is in Australia at the moment, finishing an Ice Cube tour that spanned the first half of December. He says he doesn’t remember precisely where he was when he heard about the grand jury’s decision not to indict Wilson in the Mike Brown killing—he suspects his wife told him the news—but the feeling was a familiar one. “I feel the same way: mad as fuck,” he says. “It’s the same old shit.”

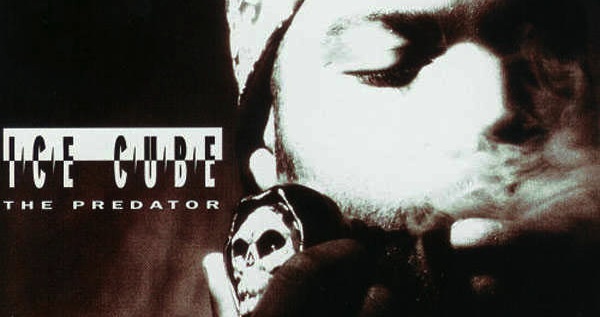

That feeling Jackson describes is the same one he felt in 1992, when a jury in Los Angeles found the four police officers accused of beating motorist Rodney King not guilty of assault and excessive force. That decision, and the days of deadly rioting that followed, fueled Jackson’s most successful album, The Predator, which ripped the verdict and the King beating as just one snapshot of a far wider culture of systemic subjugation of black people in America. The same themes underpin Jackson’s earlier albums, but rarely as poignantly as on The Predator—an album of reaction rather than prediction, equal parts journalism and hip-hop fantasy that captured a specific moment in America.

Except, those songs have refused to stay buried in the memory of racial strife in the 1990s. Two years ago, when George Zimmerman was acquitted of killing Trayvon Martin, the YouTube page for The Predator’s Rodney King verdict revenge fantasy “We Had To Tear This Mothafucka Up” came to life with commenters looking for an outlet for their outrage. Two years later, in the wake of the Mike Brown killing and the lead-up to the grand jury’s decision, the page lit up again. The old song had new life as people searched for music that captured their anger in those moments.

Jackson’s early catalogue, and The Predator especially, faces an unfortunate dichotomy: Those old songs, and their message, continue to live on among a new generation of frustrated music fans 20-odd years after Jackson wrote them. But they remain relevant in 2014 only because young, unarmed black men continue to die at the hands of cops.

Only Jackson doesn’t see it that way. As true as those songs were and perhaps continue to be, he says, the past is the past, and his old songs should stay there.

***

After Jackson left the pioneering rap group N.W.A. in 1989, for which he was the primary songwriter, he released three solo albums over the next three years: AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, Death Certificate, and The Predator. Each was more controversial, racially challenging and, ultimately, successful than the last. While it was never as critically embraced as Jackson’s first two LPs, The Predator was his most successful. Feeling pushed both politically and personally, Jackson produced his some of his most skilled work—especially on the album’s incredible Side A that included a procession of bombastic, political bangers sandwiched around a true pop hit, “Today Was A Good Day.” It debuted at number one on both the pop and R&B Billboard charts; at that time, it was the only album ever to do so. Along with his first two records and 1993’s Lethal Injection, The Predator is part of a procession of platinum records in Jackson’s early catalogue that helped shape modern hip-hop.

Jackson says he understands why the messages in that record, and his solo work before it, continue to resonate among young black men and women who view the deaths of Brown and Garner, and the subsequent decisions not to indict the police involved in those deaths, as just the latest examples of the perpetual failure of race relations in America. “I feel like these records are packed full of pain, and they’re packed full of truth,” Jackson says.

But even in those days, Jackson says, he saw The Predator as precisely what it appears to be: pure fantasy and nothing else. It was art as non-violent protest, the gangster rap version of the protest song archetype intended to be an action in and of itself and not the inspiration to take action out on the streets.

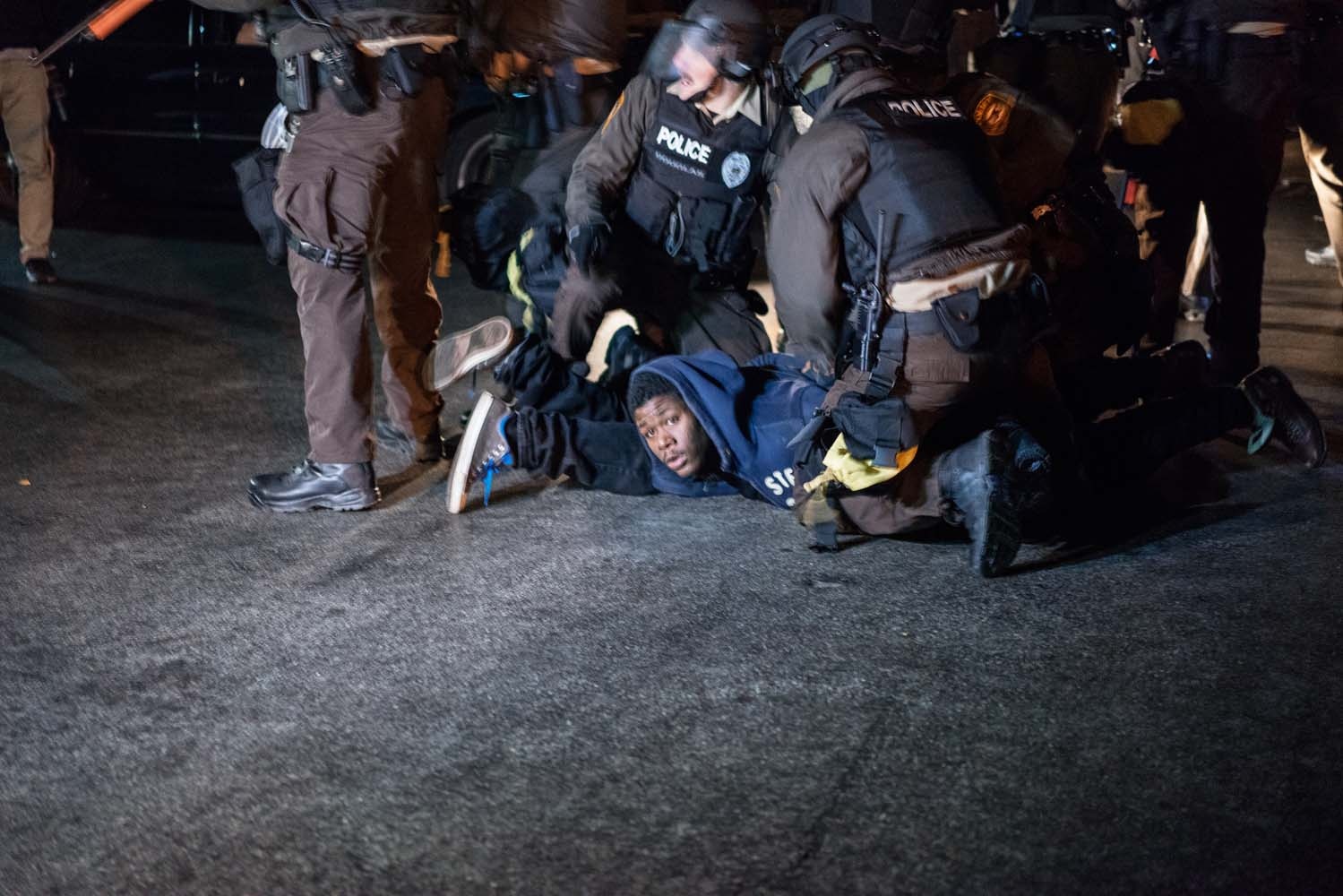

Protestors in Ferguson. Photos by Barrett Emke for Vice.com.

“They’re talking about fantasies of doing what you feel like you want to do, but in reality, you’re not going to get nothing done,” Jackson says.

Calling the songs pure fantasy is, it seems, a kind of revisionist history. Of course, The Predator has no shortage of fever-dream fantasies about finding the LAPD officers and the jury and making them pay for the beating and the verdict. But the Los Angeles riots that followed the verdict had little to do with non-violent protest; those six days were the most violent period of race-related unrest in America since the Civil War. As Jackson himself says, his songs never strayed far from the truth. Even when the lyrics were technically fiction.

It also seems counter-intuitive that the songs were not intended to inspire action. “We Had To Tear This Mothafucka Up” includes a kind of paint-by-numbers guide to looting—get the laptop, hit the Foot Locker, grab the Molotov cocktail and so on. But Jackson insists those songs were an end in themselves. “When people want to let off their frustration, I would love for them to come listen to my song, or get inspiration from my song and not go do nothing in the streets,” he says. “Not go do nothing that’s going to hurt the situation more than help the situation.”

His larger point is this: The vitriol Jackson captured in those early albums doesn’t apply to the events of today. Those songs, he says, are time capsules.

“Those records are absolutely true. But you can’t apply a record to something that’s happening right now. That’s mixing fantasy with reality,” he says. “You have to deal with the reality of what’s going on. You can’t be caught up in slogans or none of that shit.”

***

The Ice Cube story is well worn now: The groundbreaking writer for N.W.A., four platinum-selling solo albums in the early-90s heyday of gangster rap, then an abrupt turn towards his acting career—the Friday movies which he also wrote, followed by Anaconda, Three Kings, Barbershop. When he returned to music in 1998 with the first of two War & Peace albums, the sales remained, but much of that vitriol was replaced with occasional optimism—and a few crossover club hits.

Jackson pushes back against the suggestion that those early records were a kind of phase in his music career; that all the anger that made The Predator and Death Certificate so striking and dangerous was traded wholesale for club hits and PG-rated movies. The message in his music hasn’t changed, he says. The music world just moved on.

“People just listen when they tend to listen. The way that radio and pop culture are set up, it’s really just an ‘out with the old, in with the new’ kind of culture,” he says. He points to Raw Footage, his 2008 album, as another chapter in his continued push against mainstream, radio hip-hop and towards Jackson’s view of the truth.

“It’s not about pulling any punches, trying to be pop to get on the radio. That shit is raw,” Jackson says of the Raw Footage. “I’m always speaking on these things.” He expects his long-delayed new record, Everythang’s Corrupt, to drop by mid-2015. Even as a family man and Hollywood star, his message hasn’t changed, he says.

The anger survives as well. He looks at Brown and Garner and sees echoes of not only his past, but the history of blacks in America. He’s seen race relations this way since the days of AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted. It’s no different now, he says.

“It’s the same old song to me. I don’t say: Damn, in 2014, this is still happening?” Jackson says. “It’s power versus the powerless. We have been relegated to the bottom of the American totem pole since day one. And a lot of people want to keep us there. But we’re not going to stay there. That’s just the fight.”

It’s a fight he could bow out of and no one would blame him. He’s left his mark, both on rap and racial discourse. At 45, Jackson is a senior statesman in what is firmly a young man’s game. In the wake of the Brown and Garner decisions, it’s been 20-somethings who have populated protests and pushed for direct action and civil disobedience. Jackson’s voice rises from the events of yesteryear. While his songs maintain their relevance today, his voice may not in a movement driven almost wholly by young people.

But it’s not in Jackson to leave something unsaid. He’s built his career on saying exactly what he wants—even when the music industry and media pushed against it—and he doesn’t plan on stopping now.

“I can easily…” Jackson says, and hesitates. “I’ve got a good life. I can just walk off into the sunset and tell everybody: I got mine, you get yours.”

“But that’s a sucker move,” he says. “To me, you always speak on what you think is the truth, no matter what the consequences are at the end. Because nothing matters but the truth.”

Ron Knox is on Twitter – @ronmknoxdc

More

From VICE

-

(Photo by Theo Wargo/Getty Images for The T.J. Martell Foundation) -

-

Screenshot: The Game Awards -

KMazur/WireImage/Getty Images