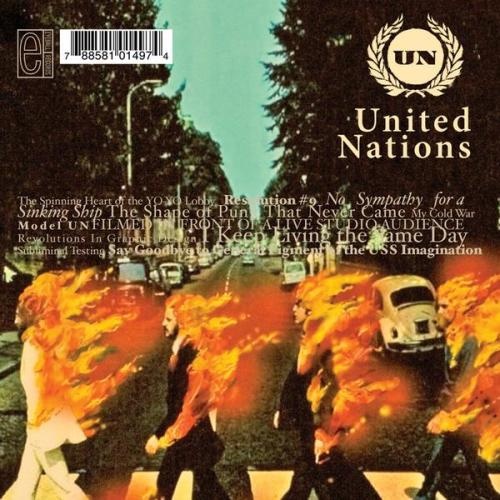

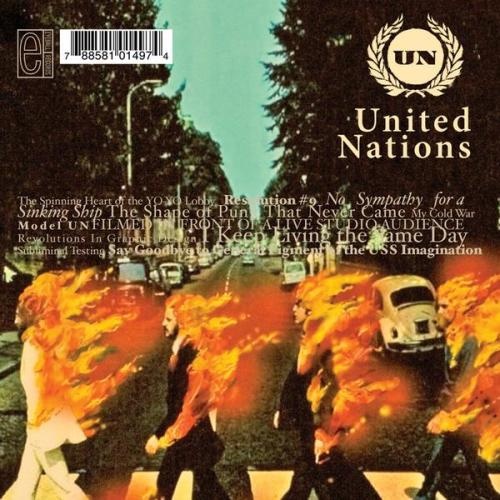

Punk bands getting themselves into trouble for infringing on trademarked and copyrighted works is nothing new. After all, punk, by definition, is about crossing boundaries and pushing buttons. (That, and how high you can spike your hair, obviously.) But when former Thursday vocalist Geoff Rickly rounded up a few semi-anonymous musicians to form a new band back in 2005, they picked the biggest possible button to push. They called themselves United Nations.In nearly a decade as a band, United Nations has had on-again, off-again dealings with the intergovernmental agency of the same name. They've also gotten themselves into trouble over the cover of their first LP, which featured the iconic Abbey Road cover, with the Beatles members engulfed in flames. Now, United Nations are about to release their second record, The Next Four Years—part album, part open challenge to the “real” United Nations, with the LP’s cover art made from the actual cease and desist letters sent by the UN.We recently spoke with singer Geoff Rickly about the band’s history, which has largely been shrouded in rumors until now… Rickly, assembling United Nations box sets. Photos by Liza de Guia.Noisey: When you were naming the band back in 2005, you had to have known some problems would arise, yeah?

Rickly, assembling United Nations box sets. Photos by Liza de Guia.Noisey: When you were naming the band back in 2005, you had to have known some problems would arise, yeah?

Geoff Rickly: That’s the funny thing: no. It actually never occurred to me. There’s no problem here clearly, that’s a government organization and no one would ever confuse the two. I was more worried about the artwork, and I was even preparing the label to print a second version of the record that was going to have a black cover, because the original had the Beatles on fire. And I figured, well obviously the Beatles will sue. Apple Records is notorious about that. So I was worried about the art, had no idea that the name would cause anything, and we never got sued for the art, and only had flak from the United Nations. But a lot of stores were scared to sell that though, right?

But a lot of stores were scared to sell that though, right?

That’s true, yeah. We had a lot of stores that wouldn’t take that cover, and we had one pretty big account retail store took, I think 7,000 copies? And when they realized there were all of these copyright violations, they have a no return policy, so they sent us pictures of them destroying the record. That was their policy, they would destroy them but they wouldn’t return them. So we have all these absurd pictures of stock boys destroying all these records.Which is unfortunate, because it’s a great record.

Oh, thanks. Yeah, it was just surreal because we were like, “I guess that makes sense, and we still get paid for them? Is that even a bad thing? Now they have to come and buy them from us.” Like maybe it was good. At that point, we were all sort of, “This is fun!” And that was before United Nations were involved.So at this point, you sort of got a taste for being provocative button-pushers. Explain how you were first contacted by the UN originally.

I think the first thing was our Facebook page being taken down.It just went down?

Yeah, it was taken down and there was maybe even one news story that was “United Nations are trying to convince us they’re being harassed by the United Nations.” And we went to the label and we’re like, “Is this you?” and they’re like, “No, is it you?” And it was like, “Ah shit, it’s either you or us, who’s messing with us?” And then our publicist called and he quit immediately because he got a letter in the mail. And he was like, “I can’t represent you guys” and we were like, “But why? You're not gonna get in trouble. You’re just representing a band that’s done something wrong." And he was like, ‘I dunno man, I smoke a lot of pot and they’re gonna come to my house and destroy my life.’” [Laughs] And I was like… “Seriously?” Then retailers would stop carrying the record, and everyone sort of jumped ship all at once. It was pretty weird. The United Nations collective, hand-making box sets.What interactions did you have with them after you got those things taken down, and that cease and desist letter?

The United Nations collective, hand-making box sets.What interactions did you have with them after you got those things taken down, and that cease and desist letter?

None, because none of the songs were copyrighted, so nothing was legally tied back to the people that were in the band. So our label was the one that decided to do it. They were like, “Well, cease and desist” so technically they stopped printing the record, but they had a shit-ton of copies. And we were like, “We’re technically ceasing, and we’ll play it that way until we get told not to.” And that’s what Eyeball kept doing until they shut down. So I think technically, the first record is out of print. Then Deathwish was like, whatever, if it’s coming out on Deathwish then the United Nations will find out anyways. At the time, that was sort of the attitude. I don’t know if that’s really their true attitude, they’re a really big small label. But the seven-inch never really got promoted; there was a pre-sale and maybe a couple articles about it. So we were all waiting to find out if we were safe now, or if it was getting re-opened. We kind of just went straight ahead to hire artists who would push buttons. We had Ben Frost who’s an Australian artist do a Sex Pistols take off.And your new record uses the cease and desist letter in the artwork, right?

Yeah, we figured we’d better double down.So are you doing anything on the new record differently to either prevent future problems or go harder with it? What approach are you guys taking with this?

Yeah, we’re going to go for it, and see how far we can get. It just seems so weird that they’d spend so much time go after a band this hard, like no one’s come to us for help and confused us with them. When this all happened, people thought you were just doing it all for press. But you really didn’t get a lot of press about it. Really, no one’s been talking about it until now.

When this all happened, people thought you were just doing it all for press. But you really didn’t get a lot of press about it. Really, no one’s been talking about it until now.

Yeah, it’s kind of funny because that’s what I told our publicist that quit. I was like, “Dude, this is a dream for you! Write it out, and we’ll make some headlines and stuff, we’ll take it to court,” and he’s like, “Yeah not with me.”Too afraid for his weed. You have a new song on the album called “United Nations vs. United Nations.” Are the lyrics specifically about this ordeal?

Right, totally, it’s completely about this. And it’s also sort of about behaviors like United Nations going out of their way to spend legal counsel’s time on a band. So, it’s kind of about them coming after us, and it’s also about us pretending to fight the man. Most punk kids who are pretending to fight the man are totally fighting who they’re going to become in five years anyways. [Laughs] So it’s like a little bit of a fuck you to ourselves too. Do you think the name and the interactions that you’ve had dealing with the actual United Nations gave the band a purpose, or at least an identity?

Do you think the name and the interactions that you’ve had dealing with the actual United Nations gave the band a purpose, or at least an identity?

Oh yeah. I think one of the things that happened with my old band Thursday was that we lost something to fight against when we didn’t have Victory anymore and we really lost our focus. I’m proud of a lot of our later work, mostly the last record, but we sort of wandered, we didn’t have anybody to fight. And that sort of gave us a vacuum of purpose for a while. And I think that was sort of the opposite with United Nations. Having this sort of weird thing happen to us, now we know what direction we’re going in, and now we know that this probably has a time limit on it, so we should go as hard as possible for the very short term we can do it.And you guys have been sort of riding it a little bit, and pushing buttons. Besides the cease and desist letters you have those shirts that poke fun at the whole thing too.

Yeah, they make fun of the lawsuit, they make fun of Black Flag, they kind of poke fun at Minor Threat for having that Urban Outfitters thing. I think it’s really funny that our counterculture, like the idea of punk or whatever, isn’t really counter, it’s a subculture, maybe. It’s a tiny version of the same culture. I think there are aspects of it that have been counterculture, like straight-edge for the right reasons is counterculture, I think veganism for the right reasons can be counterculture. But for the most part, it’s the kinds of cliques and things that become glorified and cool, and everyone’s racing to be the biggest band in the basement. It’s like, all these people share all the same values you’re supposed to like claim to be against, and you’re like, “This is so stupid, punk is so lame.” That’s kind of a lot of what United Nations has become about, it’s self-critique. It started off as social commentary, but then we realized how stupid that was because we’re just a band. And then the second seven-inch was about how dumb punk is. And then we were like, “Wait, we’re a punk band.” So now the new record’s about how stupid and pointless we are. It’s become more and more meta to the point where now I feel like we’ve actually found our thing that we do, which is a self-examination of value systems, like our own. A lot of the record’s about that.“Serious Business” is about examining white privilege from the inside. “UN Find God” is about everyone’s quest for some spiritual meaning, and how bleak that is. That can be such a vacuum in your life. “Between Two Mirrors” is about how anything can be glorified, as long as you put it in between two mirrors it stretches out forever to an infinite reflection. And that’s sort of what punk does, like one band does something and the next band says, “That’s not punk, this is punk.” Then the next band goes, “That’s not punk anymore, this is punk!” So yeah, a lot of those things came together on this record. What do you think punk of the future will be?

What do you think punk of the future will be?

Hmm, I dunno. I think it’ll be like acid-house. I think dance music is the way to go, not like Blood On The Dance Floor, but I just think somehow club culture will become the punk of the future.I want military marching bands to become punk.

I like that, military marching bands, that’s sort of the antithesis, right? I don’t know if you’ve read Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night, but there’s this great opening, and it’s something I’ve always thought was a big part of United Nations. There’s this guy sitting at a cafe with his friends, and a marching band goes by, so he stands up and starts marching with it and making fun of it, doing all these salutes and joking around. But by the end of the march, he realizes he accidentally signed up for the military, and now he’s in the war.Yeah, I think that’s how they recruit. They should have like a recruitment station in Williamsburg, where they’re like, “Hey, join the army ironically, duuuude. It'll be soooo cool to die in another country.”

Yeah! [Laughs]

Yeah, I really wish all reviews of the album could be on the actual boxset. There’s going to be a CD version, there’s going to be a digital version, but the real record itself is meant to be a box set. The idea is this fake progression from basement punk band to pretentious eight-minute long experimental, “We’re too cool for this shit we used to do” band. So it’s like the progressive steps through that. Then there are some cool things along the way, “Revolutions at Varying Speeds” is meant to be played at 33 RPM and 45 RPM, it was recorded at two speeds. So at one speed, it sounds like a doom song, like, “Oh, one thing sounds wrong but it’s pretty cool,” but you put it at 45 and it’s like, “Oh it sounds like Orchid, but some parts sound really high and weird.” And then we remixed the digital version because we wouldn’t be able to have the two speeds on the digital version, so we did a 25-minute 800x slowed down version, and it’s called “Revolutions In Real Time,” and it sounds like Sunn or something. And then there’s the song with the two endings. The thing about vinyl is it’s like a road, and the road splits, it can go one of either ways. And that’s how the album ends, you can make a change, like political change, or you can realize the problem is completely in yourself and you have to change yourself if you’re ever going to do anything. And that’s kinda how the record ends, is with choice. Even though the thing is, there’s a groove in the vinyl, so you don’t have a choice, it’s made for you.You might listen to the record five times before you get a different ending.

Possibly, yeah. Especially if your turntable isn’t level. Then it’ll probably pick one more than the other. What advice would you give to a band who’s considering naming themselves after a trademarked name?

What advice would you give to a band who’s considering naming themselves after a trademarked name?

[Laughs] Do it! It’s awesome. You’ll have the time of your life, you won’t just be a shitty band that gets to play a bunch, you’ll be a shitty band that gets to call lawyers and talk to people about the difference between a trademark and a super mark. It’s so much more fun than just playing shows and drinking beer. It’s way more fun.The Next Four Years is out on July 15 from Temporary Residence.Dan Ozzi got a cease and desist letter from Lane Bryant once. Follow him on Twitter - @danozzi

Advertisement

Geoff Rickly: That’s the funny thing: no. It actually never occurred to me. There’s no problem here clearly, that’s a government organization and no one would ever confuse the two. I was more worried about the artwork, and I was even preparing the label to print a second version of the record that was going to have a black cover, because the original had the Beatles on fire. And I figured, well obviously the Beatles will sue. Apple Records is notorious about that. So I was worried about the art, had no idea that the name would cause anything, and we never got sued for the art, and only had flak from the United Nations.

Advertisement

That’s true, yeah. We had a lot of stores that wouldn’t take that cover, and we had one pretty big account retail store took, I think 7,000 copies? And when they realized there were all of these copyright violations, they have a no return policy, so they sent us pictures of them destroying the record. That was their policy, they would destroy them but they wouldn’t return them. So we have all these absurd pictures of stock boys destroying all these records.Which is unfortunate, because it’s a great record.

Oh, thanks. Yeah, it was just surreal because we were like, “I guess that makes sense, and we still get paid for them? Is that even a bad thing? Now they have to come and buy them from us.” Like maybe it was good. At that point, we were all sort of, “This is fun!” And that was before United Nations were involved.So at this point, you sort of got a taste for being provocative button-pushers. Explain how you were first contacted by the UN originally.

I think the first thing was our Facebook page being taken down.It just went down?

Yeah, it was taken down and there was maybe even one news story that was “United Nations are trying to convince us they’re being harassed by the United Nations.” And we went to the label and we’re like, “Is this you?” and they’re like, “No, is it you?” And it was like, “Ah shit, it’s either you or us, who’s messing with us?” And then our publicist called and he quit immediately because he got a letter in the mail. And he was like, “I can’t represent you guys” and we were like, “But why? You're not gonna get in trouble. You’re just representing a band that’s done something wrong." And he was like, ‘I dunno man, I smoke a lot of pot and they’re gonna come to my house and destroy my life.’” [Laughs] And I was like… “Seriously?” Then retailers would stop carrying the record, and everyone sort of jumped ship all at once. It was pretty weird.

Advertisement

None, because none of the songs were copyrighted, so nothing was legally tied back to the people that were in the band. So our label was the one that decided to do it. They were like, “Well, cease and desist” so technically they stopped printing the record, but they had a shit-ton of copies. And we were like, “We’re technically ceasing, and we’ll play it that way until we get told not to.” And that’s what Eyeball kept doing until they shut down. So I think technically, the first record is out of print. Then Deathwish was like, whatever, if it’s coming out on Deathwish then the United Nations will find out anyways. At the time, that was sort of the attitude. I don’t know if that’s really their true attitude, they’re a really big small label. But the seven-inch never really got promoted; there was a pre-sale and maybe a couple articles about it. So we were all waiting to find out if we were safe now, or if it was getting re-opened. We kind of just went straight ahead to hire artists who would push buttons. We had Ben Frost who’s an Australian artist do a Sex Pistols take off.And your new record uses the cease and desist letter in the artwork, right?

Yeah, we figured we’d better double down.So are you doing anything on the new record differently to either prevent future problems or go harder with it? What approach are you guys taking with this?

Yeah, we’re going to go for it, and see how far we can get. It just seems so weird that they’d spend so much time go after a band this hard, like no one’s come to us for help and confused us with them.

Advertisement

Yeah, it’s kind of funny because that’s what I told our publicist that quit. I was like, “Dude, this is a dream for you! Write it out, and we’ll make some headlines and stuff, we’ll take it to court,” and he’s like, “Yeah not with me.”Too afraid for his weed. You have a new song on the album called “United Nations vs. United Nations.” Are the lyrics specifically about this ordeal?

Right, totally, it’s completely about this. And it’s also sort of about behaviors like United Nations going out of their way to spend legal counsel’s time on a band. So, it’s kind of about them coming after us, and it’s also about us pretending to fight the man. Most punk kids who are pretending to fight the man are totally fighting who they’re going to become in five years anyways. [Laughs] So it’s like a little bit of a fuck you to ourselves too.

Oh yeah. I think one of the things that happened with my old band Thursday was that we lost something to fight against when we didn’t have Victory anymore and we really lost our focus. I’m proud of a lot of our later work, mostly the last record, but we sort of wandered, we didn’t have anybody to fight. And that sort of gave us a vacuum of purpose for a while. And I think that was sort of the opposite with United Nations. Having this sort of weird thing happen to us, now we know what direction we’re going in, and now we know that this probably has a time limit on it, so we should go as hard as possible for the very short term we can do it.

Advertisement

Yeah, they make fun of the lawsuit, they make fun of Black Flag, they kind of poke fun at Minor Threat for having that Urban Outfitters thing. I think it’s really funny that our counterculture, like the idea of punk or whatever, isn’t really counter, it’s a subculture, maybe. It’s a tiny version of the same culture. I think there are aspects of it that have been counterculture, like straight-edge for the right reasons is counterculture, I think veganism for the right reasons can be counterculture. But for the most part, it’s the kinds of cliques and things that become glorified and cool, and everyone’s racing to be the biggest band in the basement. It’s like, all these people share all the same values you’re supposed to like claim to be against, and you’re like, “This is so stupid, punk is so lame.” That’s kind of a lot of what United Nations has become about, it’s self-critique. It started off as social commentary, but then we realized how stupid that was because we’re just a band. And then the second seven-inch was about how dumb punk is. And then we were like, “Wait, we’re a punk band.” So now the new record’s about how stupid and pointless we are. It’s become more and more meta to the point where now I feel like we’ve actually found our thing that we do, which is a self-examination of value systems, like our own. A lot of the record’s about that.

Advertisement

Hmm, I dunno. I think it’ll be like acid-house. I think dance music is the way to go, not like Blood On The Dance Floor, but I just think somehow club culture will become the punk of the future.I want military marching bands to become punk.

I like that, military marching bands, that’s sort of the antithesis, right? I don’t know if you’ve read Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night, but there’s this great opening, and it’s something I’ve always thought was a big part of United Nations. There’s this guy sitting at a cafe with his friends, and a marching band goes by, so he stands up and starts marching with it and making fun of it, doing all these salutes and joking around. But by the end of the march, he realizes he accidentally signed up for the military, and now he’s in the war.

Advertisement

Yeah! [Laughs]

So switching gears completely, I wanted to ask you about the record itself. I hear there are a lot of really cool hidden things on this record, like some things play differently at the ends of the vinyl?

Yeah, I really wish all reviews of the album could be on the actual boxset. There’s going to be a CD version, there’s going to be a digital version, but the real record itself is meant to be a box set. The idea is this fake progression from basement punk band to pretentious eight-minute long experimental, “We’re too cool for this shit we used to do” band. So it’s like the progressive steps through that. Then there are some cool things along the way, “Revolutions at Varying Speeds” is meant to be played at 33 RPM and 45 RPM, it was recorded at two speeds. So at one speed, it sounds like a doom song, like, “Oh, one thing sounds wrong but it’s pretty cool,” but you put it at 45 and it’s like, “Oh it sounds like Orchid, but some parts sound really high and weird.” And then we remixed the digital version because we wouldn’t be able to have the two speeds on the digital version, so we did a 25-minute 800x slowed down version, and it’s called “Revolutions In Real Time,” and it sounds like Sunn or something. And then there’s the song with the two endings. The thing about vinyl is it’s like a road, and the road splits, it can go one of either ways. And that’s how the album ends, you can make a change, like political change, or you can realize the problem is completely in yourself and you have to change yourself if you’re ever going to do anything. And that’s kinda how the record ends, is with choice. Even though the thing is, there’s a groove in the vinyl, so you don’t have a choice, it’s made for you.You might listen to the record five times before you get a different ending.

Possibly, yeah. Especially if your turntable isn’t level. Then it’ll probably pick one more than the other.

[Laughs] Do it! It’s awesome. You’ll have the time of your life, you won’t just be a shitty band that gets to play a bunch, you’ll be a shitty band that gets to call lawyers and talk to people about the difference between a trademark and a super mark. It’s so much more fun than just playing shows and drinking beer. It’s way more fun.The Next Four Years is out on July 15 from Temporary Residence.Dan Ozzi got a cease and desist letter from Lane Bryant once. Follow him on Twitter - @danozzi