Welcome to Waypoint’s Pantheon of Games, a celebration of our favorite games, a re-imagining of the year’s best characters, and an exploration of the 2017’s most significant trends.

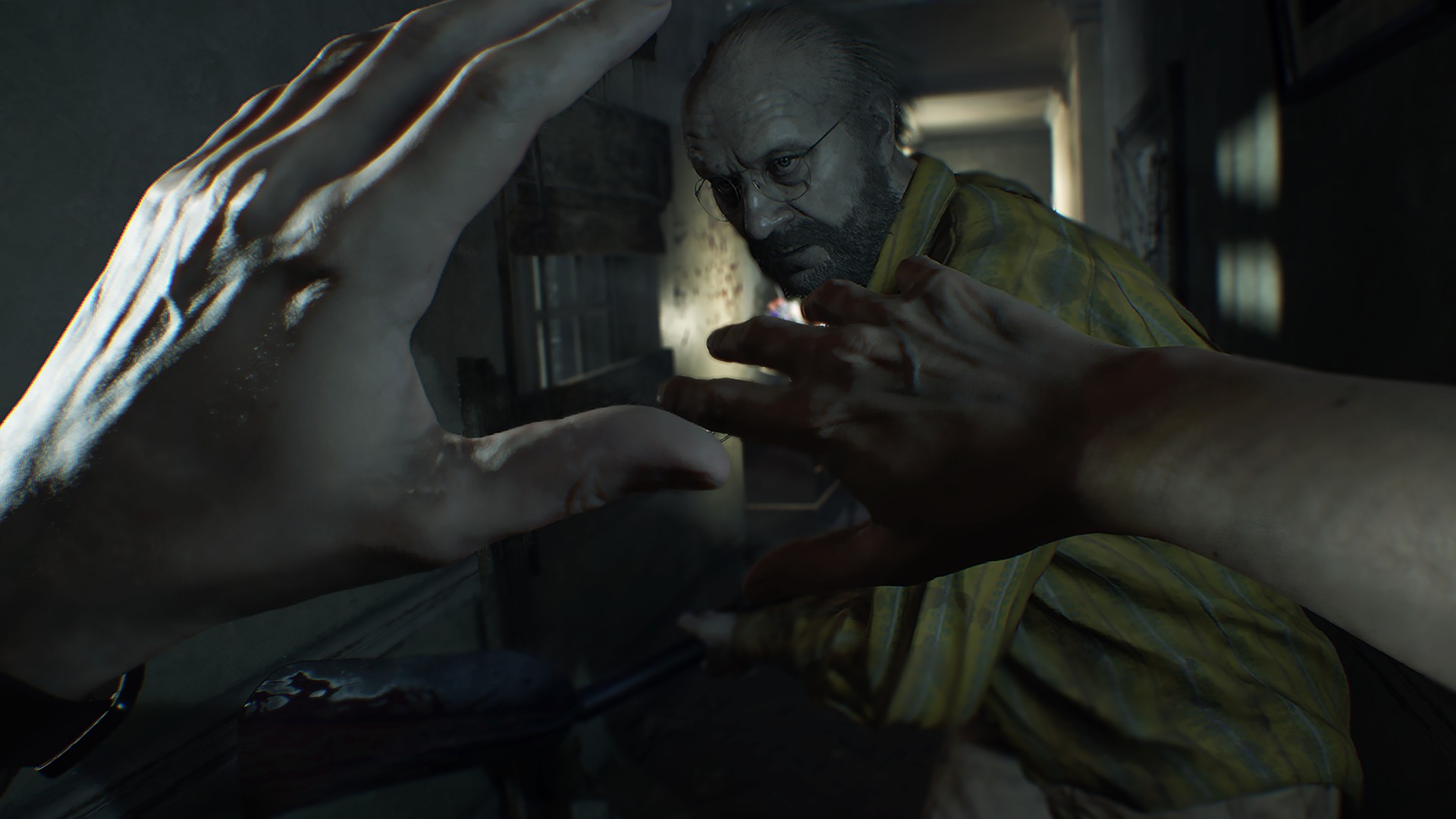

10. Resident Evil 7

Fear is not an easy thing for a survival horror-action game to sustain. The “action” part of the equation usually breaks the suspense. We tend to want our action games to feel satisfying and empowering, but that’s 180 degrees from what a great horror experience wants to evoke. Which is probably why so few horror games even want to fight that battle anymore, or fight any battle of any kind. Games like Amnesia and Alien: Isolation or—more illustratively but less elegantly— Outlast resolve the tension by removing action entirely. They are games of flight without fight, and this can make them terrifying vessels for horror.

Videos by VICE

But there is something especially awful and harrowing about the game where you can fight back, you can save yourself, but you can’t afford any mistakes and death is always bearing down on you, and there is always the thought, as it approaches, that maybe you should have run after all.

Resident Evil 7 is dreadful. Every scene, every space, practically every object feels like something to be rejected. Even at the start of the game in the light of day, the sky itself seems toxic. The rambling Southern estate grounds where it takes place are not just decayed but diseased, ravaged by far more than time and the elements. Nature, science, even the human form itself has all be made twisted and repugnant, and at every turn you are made to wade deeper into the mire.

Some enemies are not meant to be fought, some can’t be, but there are also a lot of places where the only way out is through. You have to fight, and in order to survive the fight you have to master your terror and locate your presence of mind. Stop running, turn around. Stop shaking, aim.

It’s okay to be afraid, you’re meant to be afraid. But Resident Evil reminds you that if you want to survive, you’re going to have to be brave.

9. Motorsport Manager

This is a 2016 game that ended up really capturing my imagination in 2017, which is ironic in a year that saw new editions of Gran Turismo, Forza, Project CARS, and F1 2017. Confronted with an almost unprecedented banquet of racing sims, it’s suitably ironic that I would end up investing most of my racing time into this delightful little sports management game from last year.

It does a terrific job unpacking the strategy and politics of auto-racing, about all the important choices that are made before a driver first sits down inside a car on race day. What parts does your R&D team create for the car, and should they focus on risky, high-performance equipment or tune for durability and reliability? Do you gamble that a your best driver can stretch a worn-out set of tires to the end of a race, at the very real risk of watching them smash into a corner wall or simply start crawling around the track?

While racing is most vividly depicted from the perspective of the driver, Motorsport Manager reminds us that racing is, after all, a strategy game.

8. Battlestar Galactica: Deadlock

This is such a flawed game that misses so much of what I loved about the TV series… and yet it’s also one of the most enjoyable tactical games of the year. It could and should perhaps have been much more ambitious in the kind of story it tells, since the narrative and tragic worldview of the 2000s Battlestar Galactica TV series was what made it more than a run-of-the-mill military sci-fi show. But damn if Deadlock doesn’t end up delivering a lot of great military sci-fi flavor.

I feel a bit sheepish putting this on my list when I have such reservations about it, but it was one of the games I kept returning to throughout this fall. Maneuvering its warships in battle, plotting out delicate maneuvers in its simultaneous-turn interface, and watching massive fleets just unload on each other with walls of artillery, missiles, and flak is a lot of what what I want from a game like this. Not everything, but enough to make it one of my games of the year.

7. MLB: The Show 17

This was the year I got into The Show, and frankly into baseball. It’s impossible for me to separate my affection for The Show 17 from my experience watching the Cubs win the World Series last fall, and from its opening cinematic The Show 17 is openly pandering to me by presenting Kris Bryant’s play on the final out of the Cubs-Indians series as the apotheosis of baseball history.

I’m late to the party on The Show and certainly don’t want to present myself as any kind of expert on the series. I have no idea if the 2017 edition is a significant improvement on what the series has already achieved, but as someone coming to it fresh, it felt like a tremendous re-creation of baseball. Not just the game itself, but the entire feel of the game. The commentary from Matt Vasgersian, Harold Reynolds, and Dan Plesac is incredibly well-done and feels shockingly reactive to what’s happening in each game. I’ve played hundreds of games of The Show 17 and it still feels a little bit like I’m taking part in a live broadcast.

Far more importantly, though, The Show 17 captures the all the decision-making and guesswork that goes on inside a baseball game. You send a signal to the mound, weighing a pitcher’s fading arm against his can’t-miss sinker, offset by a terrifying left-handed batter’s nuclear explosiveness against low, outside pitches. Will he be set-up, waiting for that pitch, or will he outsmart himself, guessing that you’d never throw him the pitch he wants? The count is loaded, two men on, and for a moment you you can feel that cool autumn night air against the back of your neck, that sense that the future is about to happen and right now you have it in your hands, it can still be changed, but you know it’s right there across the sixty feet to home plate, waiting for you to let it go.

6. Wolfenstein: The New Colossus

(Heads up, some spoilers for the game are ahead, so feel free to skip ahead to the next entry if you’d like to avoid those.)

The New Colossus was one of my biggest disappointments this year, as well as one of my favorite games. The latter is why it appears on this list, the former is why it didn’t land higher.

There is little that I loved about playing the new Wolfenstein installment from Machine Games. It’s most breathtaking settings and conceits were for cutscenes and “look, don’t touch” sequences in which you explored your way from one combat area to the next. When it came to the actual gunplay, The New Colossus generally kept me bouncing between combat arenas and long, jogging corridors full of cover positions, just waiting to be turned into shooting galleries. There were exceptions, like a brutal series of firefights inside a Louisiana waterfront warehouse, or the bomb-blasted streets outside a New York police headquarters, but as a shooter The New Colossus felt like an uninspired evolution of its predecessor.

But then there’s a long walk through down a sun-drenched Main Street USA under a too-comfortable Nazi occupation, replete with strutting Klansmen and relentlessly obsequious middle Americans, all of whom fear each other and the possibility that one day the violence of the state will be turned on them.

Or there’s garish burlesque of Hitler’s Venusian Berchtesgaden, where the Fuhrer has turned into late-era Howard Hughes by way of Tommy Wiseau. Or there’s just the quiet pace of life of the resistance aboard their submarine HQ, where new resistance groups meet, mingle, and slowly merge their respective movements and grievances into one unified force, a story that is told through small exchanges and little gestures between characters.

And of course, there’s Max Hass, who reveals something so ambitious and beautiful that it renders one of the characters who sees it speechless.

5. Night in the Woods

There are countless versions of the young person returning to their hometown after a long absence, discovering that “things have changed” or that perhaps they never really were as simple as a child believes them to be. There is an element of condescension inherent to this story: every generation, it says, goes through this, and eventually becomes the adults they reject.

What sets Night in the Woods apart is its specificity to a particular time, place, and people. This is not a story about growing up, but about what it’s been like to grow up in working-class, ex-industrial America in an era when security and opportunity seem have been as effectively shuttered and locked-away as the countless mines, mills, and factories that were once the foundation of reasonably prosperous working-class communities. Its charming writing and sense of humor, and gorgeous, slightly unsettling art (there’s a chapter called “Weird Autumn” which could perhaps double as the game’s visual mission statement) help lessen the sting of this story, but darkness is present throughout.

One of the first things your character notes in her journal when she gets home is that her father looks suddenly old, and it’s easy to see that her parents in their late middle age are working harder at less stable jobs, and there’s no retirement within sight for them. Dread and frustration are in the margins of every conversation and every frame of this story about “the Millennials,” and Night in the Woods depicts just how fragile and artificial is the carefree, frivolous life of person growing up in those parts of America for whom the the recession became—without anyone noticing or caring until it was far too late—a vast, selective depression.

In a year when major media outlets marveled at the Reagan-esque simplicities of Ben Sasse’s frayed bromides and J.D. Vance’s dubious anecdotes, or extolled the visionary successes of Dollar General, Night in the Woods is better informed, more compassionate, and more important portrait of America than any of them.

4. Tacoma

Has there ever been a more disappointing vision of space travel and extraterrestrial colonization than Tacoma? Has there ever been one that rang quite so true?

We live in the future, or at least in a version of the future that always seemed miraculous in the abstract. But we got here without solving any important problems and by inventing quite a few new ones: vast sections of the economy are under the sway of a dwindling number of oligopolists-cum-monopolists. “Economic growth” no longer means anything to people who work for a living: they don’t see the gains, and are instead made to compete for contracts and service gigs. Work that provides a stable income and decent health and retirement benefits is a dream for far too many of us. For those lucky enough to have a job that with good benefits, they are basically handcuffs that make it increasingly difficult to leave employers.

The wonders of modern technology and communications have largely enabled trivial innovation in the form of greater conveniences, devoid of real material benefit to either workers or consumers. This is the Gilded Age of the Electronic Middleman and the Make-Believe Visionary, and they have their sights set on the stars.

But Tacoma is not just a jeremiad against a mediocre future. It’s also an innovative kind of digital stage-play, a performance-oriented evolution of what Fullbright did with Gone Home. Most of what it depicts are the ordinary people doing make-work jobs for an employer that desperately wants to lose headcount by any means necessary. A twee, ruthless form of capitalism looms over every exchange between these superb cast members, but for the most part we learn about this world from the hopes and anxieties of Tacoma’s characters.

It’s a dystopian sci-fi suspense story about wondering if you can afford to leave a job you hate, to live with the person you love, or to send a child to the school they dream of attending, all while waiting to be discarded by a system that has no further use for you.

3. XCOM 2: War of the Chosen

2017 was the year I fell back in love with XCOM, and more deeply than at any point since Firaxis released the first game. There is no shortage of places where I’ve talked about my admiration for what the War of the Chosen expansion added, or its new emotional texture and sense of real stakes at risk, or my remaining reservations about XCOM 2’s game balance and structure.

But I feel like War of the Chosen is the first iteration of Firaxis’ XCOM that unequivocally improves on the original game. Where in the past I always felt like Enemy Within had good ideas that didn’t really add up to major improvements over the streamlined perfection of the core game, and thought XCOM 2 amounted to a grab bag of unevenly implemented concepts for a sequel rather than a great sequel itself, War of the Chosen manages to bring everything that Firaxis added over the years together in a package that’s as taut and satisfying as the original XCOM: Enemy Unknown.

2. Assassin’s Creed Origins

(Heads up, some spoilers for the game are ahead, so feel free to skip ahead to the next entry if you’d like to avoid those.)

There was a time when things were true. When there were rules and if they were not perfect they might at least be clear and reasonably fair. Fair enough, at any rate, for people like us to carve out a life for ourselves. Nothing grand, nothing that would demand monuments to our achievements or our crimes (we already live in the shadow of enough of those)—just a small, decent life built around community and love.

It wasn’t much to ask but it was too much to let us keep and so here we all are, swept off the banks of civilization into the current of history. Here is where it begins.

And here at the beginning, we at last see why any of this matters. To us, and to the people involved in the stories of the Assassin’s Creed series. Origins takes the tired format of the “origin story” and manages to spin resonant, redemptive tragedy out of it. There is an early moment when the two main characters, Bayek and Aya, genuinely think they’ve successfully avenged their murdered son and can go back to being a happy family in the backwater of an aging empire.

But then Bayek starts to wonder if the evil of powerful men and their interests could really be so straightforward. In an ironic inversion of how the game will end, Aya begs him to let it go and trust that their work in complete. And from our position outside the narrative, knowing where history will take them, it’s easy to wish for a moment that they could walk away and once again be happy, and ignored.

But Assassin’s Creed Origins is about the impossibility of going back to sleep once you’ve truly comprehended the depths of the avarice, cruelty, and manipulation unleashed by elites on the everyday people of the world. When Aya first utters a variation on the titular creed we’ve all come to know, it is weighted with a meaning it’s rarely had before in this series.

1. Prey

You don’t need to tell me about every serious flaw that haunts Prey, particularly in its later stages. Exasperation and adoration were close companions during my playthrough of Arkane’s sci-fi immersive sim. Even setting aside a comically frustrating series of trips through the zero-gravity interior shaft of Talos I space station, Prey is a game that eventually runs out of ways to accommodate its own flexibility.

But Prey captivated me more than any other game I played this year. It’s opening hours provided genuine shocks that left me both terrified, yet delighted at how effectively the game was playing with the inherent artifice of its medium and the expectations players have for how games behave. While Prey never comes close to matching those opening hours in terms of narrative finesse and game balance, especially with the dread and paranoia induced by the Mimic, Prey’s opening pulled me into its world and with style and panache.

What has kept me there is the world of the Talos I space station, a midcentury modern design design studio launched into space and occupying a crossroads between the vain vacuity of modern corporate culture and the idealized postwar union of science and industry that made gave us the Rocket Age. It’s Bioshock if Rapture had been built by a patent lawyer and TED speaker.

Put another way, in the world of Prey we got the future that the old utopian World’s Fairs dreamed of… and we still fucked it all up. It was privatized and sold, and then the fate of that future was entrusted to the rational self-interest of corporate institutions and the children of oligarchs.

And so too were the fates of Prey’s characters: People whose lives are relatable and human-scale even on a space station gazing down on earth from moon orbit. They nourished small dreams and hopes and disappointments that made their eventual fates all the more sad and affecting. Talos I felt like a place anyone might end up working, and might lie awake at night wondering why they weren’t more grateful to have a good job that anyone would be glad to have, and quietly hating themselves for not being brave enough to leave.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: 505 Games -

Screenshots: Sega, Nintendo, Square Enix -

Screenshot: Team17 -

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki