Robot Koch after recording with Chaganji (left) and histraditional Rajasthani band.This photo and others accompanying the interview from the Magnetic Fields Festival are by Sachin Soni. All gallery photos at the bottom are courtesy of the artist.

There are at most three associations the average Westerner has with electronic music on the sub-continent: psy-trance raves in Goa, bhangra hip-hop in all its forms (with a lot of auto tune to boot) and maybe the occasional dubstep tune with an “exotic”-sounding Indian sample woven into the mix. Chase and Status, anyone?

But hold up, we’re talking about 1.2 billion people, aren’t we? So unless you’re reading this from China or India, that means you can take your country’s population and add a zero or two at the end and you’ll have a reasonable approximation of how many listeners that is. So there’s got to be more going on there than just artists named things like Hallucinogen and Punjabi MC. And as it turns out, there is.

Videos by VICE

I’d already gotten a small glimpse into India’s underground scene via my collaborators at Surya Dub, a Bay Area party I helped found that focused on global beats and bass. Two of the core members, Maneesh The Twister and the producer Kush Arora, were are always making the pilgrimage back to India for some wedding or another, and along the way they’d have reports of parties blending reggae, hip-hop, and heavy bass together with house and pop. These parties would go off. Kush would always say that Munbir Chawla, the event organizer and editor of Indian music blog The Wild City, was the dude to talk to in India when it comes to the kind of parties we’d all frequent if we lived there.

I found out that Munbir’s lines of connection don’t just flow to San Francisco. They also reach Berlin, and he’d been following my friend Robert Koch’s future beat productions for some time as well. It makes sense—Robert’s pedigree is undeniable and international: he’s been the production brain-center of his band Jahcoozi for nearly a decade, and he’s the flagship solo artist for the Project Mooncircle label, with three full lengths under his belt as Robot Koch. He travels a ton and collaborates all the time with singers and MCs around the world like John Robinson and Graciela Maria, producers like Submerse and Seiren, and most recently with filmmakers like Lukas Feigelfeld. His most recent project is the soundtrack for Fiegelfeld’s short film Unpaved, also on Project Mooncircle.

Munbir always believed that Robot Koch and his music could work in India, and it has a lot to do with Koch’s amazing magnetism—people are instantly drawn to him. He’s got this air of quiet mystery that makes you want to learn more, but never veers off into aloofness. Fans hear all that in his music as well, which trades in a special blend of hip-hop, hypercolor synths, and glitched-out rhythms that might have once been called IDM. He finds the sweet spot between party-starter and chin-stroker, imbuing his music with a depth of feeling that never reaches schmaltz-y or maudlin heights.

At first Robert was skeptical of an India tour, but Munbir won him over and Koch managed to squeeze in three weeks there in December—just before packing up to spend six months in Los Angeles escaping the Berlin winter. He talks to THUMP about his time in India, his impressions of the place before and after his trip, and gives us an exclusive look at his tour photos from along the way.

THUMP: Robert, how did you end up getting to go to India for these shows in the first place?

Robot Koch: Munbir Chawla, who runs The Wild City blog as well as the Magnetic Fields festival, got in touch through my friend Gerriet Schulz, who works for Border Movement, a sub-division of the Goethe Institute. Border Movement runs these music exchange programs between Germany and South Asia, and Gerreit and Munbir had met through a Soundcamp they did together in Delhi.

What shows did you end up playing there?

The first was at the IndiEarth Festival in Chennai, more like a world music festival, but also pretty open to electronic music. And I ended up doing a production workshop there as well. The second was at Magnetic Fields, which was at the Alsisar Mahal in Rajasthan, about 12 hours from Delhi. The last one was in Mumbai at a club together with V.I.V.E.K. and Engine-Earz, both from the UK.

You’ve said the IndiEarth Festival was weird. How so?

It was in this five star hotel lounge. Which is because in India the liquor licenses are mainly in the hotels, so that means the clubs are all pretty posh places. There isn’t a subculture like we have in Berlin of improvised venues and bars. I remember thinking ‘There’s no way in Hell my stuff is going to work in here’. But it actually turned out to be a really fun set – everybody got into it. People told me afterwards that it wasn’t typical for people to start dancing in that place, especially to music they’d never heard before.

All the other artists were playing in the lobby and other spots throughout the hotel. I did get to catch this dope artist named Christine Salem from La Réunion. Just two drummers and then her on vocals. World music in a way but super intense and super percussive. I talked to her manager afterwards and told him that this could go off in a club—two crazy percussionists and her singing with so much energy—and everyone dancing in this hotel lobby by the end. It was pretty surreal.

Robot Koch performing at the Magnetic Fields festival in Shekawati, Rajasthan.

What were your impressions of the Magnetic Fields festival?

I’ve played at a lot of festivals but this has to be one of the most special ones I’ve ever done, both because of the location and because of the energy. It’s in the desert, about a twelve hour drive from Delhi (at least that’s how long it took us to get there). It’s in this old palace run by a prince who turned it into a hotel, really amazing, like nothing I’d ever seen before. The programming was great, a balance between electronic and non-electronic music and between Indian and European artists. From Europe there was me, V.I.V.E.K, Engine Earz and my friend Sasha, Perera Elsewhere, as well as a couple others from the UK. And then a fair amount of Indian artists I’d never heard of that I got to discover.

It was the first time the festival took place, so it wasn’t as big as it probably will be in the next couple years—maybe around 700 people or so? But I think it has a good future since a lot of people who went said it was hands down one of the best things they’d ever been to. The energy was all there—it’s not even really something I did, I just played my set but the sound was good, they didn’t cut costs on the speakers so it was massive, plus I got to play at a peak moment of the festival, so everyone was there.

And that was all helped by the festival’s promo video, right? Magnetic Fields Festival – Teaser from Magnetic Fields Festival on Vimeo.Yes—so this is what made it so perfect. Originally, months and months ago, the organizers made a video of the doorman of the palace dancing to my song “Cloud City.” Just to promote the festival in general. This traditional turban-wearing guy name Chaganji, who stands there the whole year guarding the door to the palace. But they got him to dance because he also plays in a traditional Rajasthani band. And the video ended up going viral and being associated with the excitement for Magnetic Fields.

So then, right before I performed, Chaganji came out and did the dance again and then I ended up playing “Cloud City” in my set—a lot of people told me later that this was THE festival moment for them, because the song had been built up as the festival anthem, plus we had the guy there to do the dance. That’s what I mean that the energy was just locked—it was a really special moment.

Tell us about some of the Indian producers you discovered while there.

It was Sandunes on the first day that blew my mind, she’s doing some house and garage stuff with swung beats. On the second day I really liked this guy called Curtain Blue, who’s somewhere between Apparat and Jon Hopkins, a bit sound track-y, melancholic but really detailed production.

There was this really great post-rock band called Until We Last, sort of like This Will Destroy You or Explosions in the Sky but with a twist. All really young unsigned kids from Delhi. This artist Frame By Frame was also cool.

Also the guy who discovered acid house by accident—Charanjit Singh—he played, and just on a human level it was a very cool experience to get to see him. I wasn’t blown away musically, to be honest, but people loved it. All acid-y 303 sounds and then this 80-year-old sweet guy standing there playing it. His wife was sitting on the stage behind him, and she would talk to him while he’s performing and he couldn’t hear her at all with the loud monitors right there. He performed all of 10 Ragas to a Disco Beat along side the Dutch DJ/Producer that helped re-discover it. It was pretty epic to see just for what it was, you could tell the audience was so proud.

Recording at the Alsisar Mahal hotel in Northern India.

I know you like to record sounds while you travel—what did you get this time?

I got to have a session with the traditional local Rajasthani Chung band that Chaganji was in. These are all village people that literally work in the fields during the day and then perform at the palace at night for visitors. So I just borrowed some mics from the front of house guys and recorded the traditional drums, the flute, and the singing.

I also bought this electric tanpura, this box that creates a drone for you to practice a sitar over. Apparently Munbir told me that Modeselektor bought the same box a week before—he promoted their show as well and he told them about it just as much as he told me and they were also like, “We’ve got to get this box!”

I also did a lot of field recording in Chennai, things like elevator sounds—this weird Indian voice announcing “the doors are closing’ with this sweet little jingly sound coming before it. Street sound in India is crazy loud, noise pollution everywhere, and there were so many percussive things in the city. You can just sample anything you find a little percussive moment in. I now have a lot of stuff on my hard-drive, we’ll see how much I can make out of it.

How did you impressions of the music scene in India change after you went there?

I’ve traveled a fair bit but India was one of the places I wasn’t sure that I wanted to go. Both because I didn’t really know about the music scene there and because what I did know didn’t really attract me, like images of full-moon raves in Goa. But when Munbir asked me to play Magnetic Fields and I saw some pictures of this old palace in the desert where it was going to be, I decided I wanted to go find out about it for myself. And it actually turned out to be one of the best parties of my life. It was like that for a lot of stuff there, me learning that India really wasn’t what I thought it was in many ways.

With 1.2 billion people, it has every music scene you can imagine—even very specialized stuff like this post-rock band Until We Last, who admire Western music and then make their own version of it. And there’s all kinds of club music in India. The mainstream is dominated by this Goa beach music with Paul Van Dyk, but there’s so much more. Sandunes, for example— she’s only played once in Europe, but she gigs around in India—flying to Delhi to play a little club show there, or Absolute Vodka doing an event somewhere at the beach and they’ll fly her over to warm up for some bigger DJ. So these people work, they’re actually professionally doing it. And I didn’t have any idea about that before, I thought our scene was not existent there.

There’s also a lot of expats in India—Munbir’s British but has Indian parents, for example, and I think a lot of people are moving back there, bringing stuff they’ve experienced abroad and driving the scene with new imports and impulses. V.I.V.E.K. said to me that it’s a sleeping giant and I agree—if you just imagine how much potential there is just in manpower and possible interested in this music. There’s a huge gap between rich and poor of course, but the middle class is growing. People can afford to care about this kind of music and not only worry about the basics, which it takes for a scene to grow, because people there are really into music but they have things to worry about other than club shows.

For me personally, if I had to use just one word to describe the whole experience it would be “inspiring.”

Morning yoga on the roof with the Magnetic Fields festival’s instructor. Jahcoozi singer and solo artist Sasha Perera is seated to Robert’s left.

Speaking of inspiring, do you think there will be a beat scene that arises in India?

I think so. Maybe not because of me—when I taught that workshop in Chennai, out of twenty people only one knew who I was. But now they all have my music and they’re all writing to me and asking me production questions. Which is definitely cool to inspire people—that’s what I thrive on and it’s what I want to pass on to others. So I can’t say for sure whether there will be a beat scene there, but there’s definitely twenty kids in Chennai right now exploring beats!

Finally—plans for 2014? Any other exotic lands on the travel agenda?

Yes actually! I’m moving to Los Angeles in mid-January for a Berlin sabbatical. I’ve been here 13 winters in a row so it’s time to check out the scene somewhere else for a bit—I’ve got a three-year visa for the US so I’m going to explore what LA and the West Coast has to offer in terms of inspiration, sounds and collaborations. Other than that, my project Robots Don’t Sleep has a full length coming out next month, and some artists I’ve done production and remix work for, like the Pentatones, should see some releases as well.

Matt Earp is the DJ and writer Kid Kameleon. He currently lives in Berlin. Follow him on Twitter -@kidkameleon

My production workshop students at the IndiEarth festival in Chennai.

IndiEarth workshop students after lessons with the teacher.

Trucker on the road to the Magnetic Fields festival.

Why such a small door? At the entrance of a so called Havali in the village close to the festival.

Old account books from colonial times.

Cows are everywhere in India. This one was at the village near Alsisar Mahal.

Old Havali (Palace of the Winds).

Camel on the road in Rajasthan.

Kids posing in Rajasthan.

Peacocks are everywhere in Northern India.

Artist hotel next to the palace in Alsisar Mahal.

Sunset in Rajasthan.

The roof of the Alsisar Mahal at sunset.

From blinged out trucks to blinged out tractors. This one’s in Rajasthan.

Courtyard of the Alsisar Mahal.

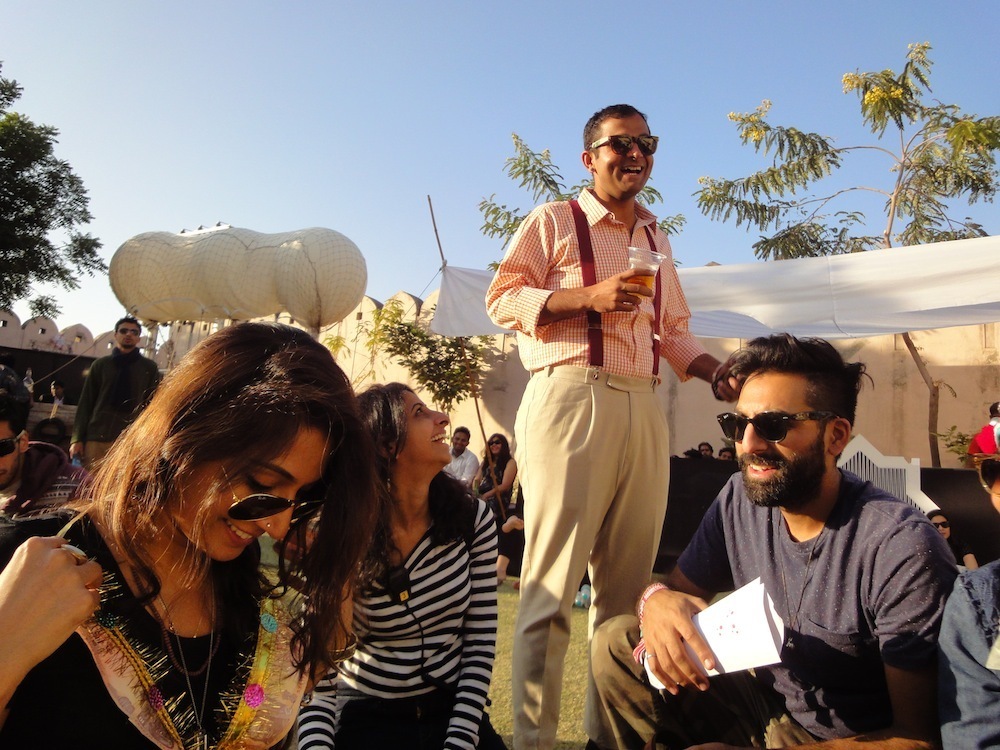

Magnetic Fields attendees, including The Prince (standing) and Kunal (right), two of the organizers of the Magnetic Fields festival.

Perera Elsewhere at the roof of Alsisar Mahal.