Ron Gilbert has been making video games for over 30 years. His big break, Maniac Mansion—which the Oregon native wrote, designed and directed—was released in 1987 by Lucasfilm Games, and almost single-handedly took the graphic adventure genre from niche concern amongst an endless sea of shooters and platformers to something close to a gaming phenomenon, one point and click at a time.

After Maniac Mansion, Gilbert worked on The Secret of Monkey Island and its sequel; Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure; and Zak McKraken and the Alien Mindbenders, before leaving Lucasfilm Games—later renamed LucasArts—to pursue new challenges. While he came back to graphic adventures in 2009, providing valuable guidance to Telltale Games for its Tales of Monkey Island series, it’s really with this year’s Thimbleweed Park that Gilbert’s reconnecting with the games that he first made, which in turn made him, reputation wise.

Videos by VICE

Which is to say: this is an adventure quite out of time with 2017’s gaming landscape.

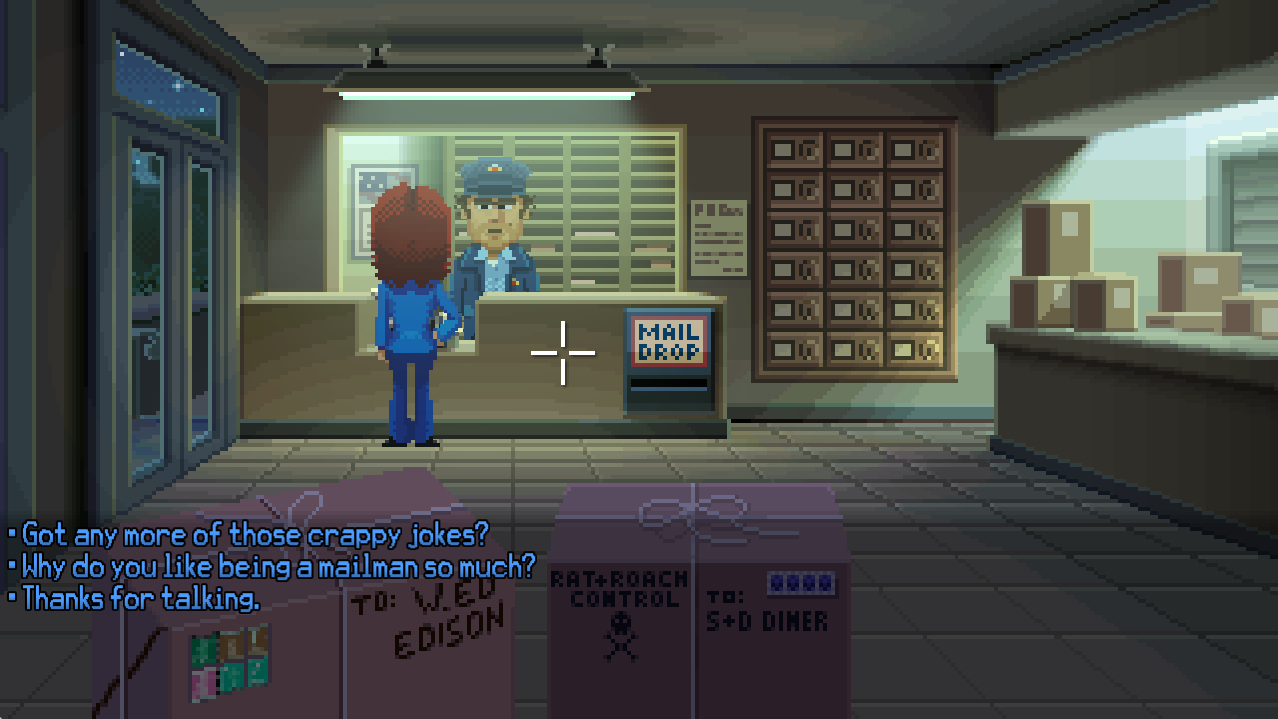

“The point of this project was very much to build a game that was evocative of how you remember the old adventure titles,” Gilbert tells me, moments after I’ve seen a decent slice of Thimbleweed Park in meticulous, mystery-unpicking action, all “Pick up” this and “Look at” that. “We’ve used pixel art less as a retro thing, and more because we just love it. That aside, we’ve not really limited ourselves in what we could do, making this game. I have no list of dos and don’ts that we followed. We just went with what felt right.”

All Thimbleweed Park screenshots courtesy of Terrible Toybox.

Thimbleweed Park follows the fortunes of five very different characters, caught up in strange events unfolding in the small, rundown town that gives the game its name, and its surrounding county. There are a couple of FBI agents who don’t get along, Ray and Reyes, who have to begrudgingly work with each other and the local law enforcement tuna-heads. There’s a foul-mouthed clown by the name of Ransome who refuses to take off his makeup. And then there’s a game developer by the name of Delores and her father, Franklin, who’s a little less than alive these days.

“These days” being 1987, the year of Maniac Mansion‘s release—and that’s just one of multiple references to Gilbert’s past, and adventure gaming’s history beyond his credits, spread throughout what is quite clearly a love letter to the genre.

Which isn’t to say Thimbleweed Park‘s exclusively for those people, like me, who played their share of point-and-click adventures in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It looks archaic—deliberately, but quite beautifully so—but it’s fully voice-acted, and mercifully arrives shorn of those most-infuriating puzzles that tripped up so many in the Monkey Island days.

“I want to expose all of the great things about point and click adventures to a new audience.” — Ron Gilbert

If you were there, you’ll know what I’m talking about: the seemingly arbitrary combining of Item A with This Thing B over That Place C, in the hope of causing Supporting Character D to slip onto his arse and bring about Game Progressing Event E. Did I lose you, in the middle of that? You, and thousands of other players, back when.

“I want to expose all of the great things about point and click adventures to a new audience,” Gilbertsays. “I think younger players get caught up in a little bit of nostalgia when they hear about the Nintendo era, the point and click era, the mystique of these games. It’s interesting to them, but when they go back and actually play those games, they realize how crude they were.

“So, Thimbleweed is about letting them relive and understand what those games were, but through a game that has all of the stupid stuff removed from it. It’s challenging, but without the confusion. We give you all the pieces you need to solve any puzzle in this game, and nothing is too obtuse. We specifically removed all that. Everything is logical.”

Play testing has helped—we’ve come a long way from the once-through quality assurance of the first Monkey Island. Thimbleweed Park, Gilbert explains, has been tested some 30 times, with the small team at Terrible Toybox—Gilbert plus Maniac Mansion co-designer Gary Winnick, alongside a handful of others—closely monitoring where people got stuck, where they became frustrated, and seeing what they could do to make the experience easier to understand, while still testing the grey matter.

“We got to see the player’s gears turning in their heads,” Gilbert says. “Back in the day, we wouldn’t give you enough clues. This time, we’ve been able to refine the game so that it best respects the player, while not making anything too simple.”

Thimbleweed Park does feature a puzzles-pulled-back “Casual” mode, but Gilbert and coder Jenn Sandercock explain that even newcomers to adventures like this should play on “Normal” first, to better understand how all of the components in cracking its murder case—which is ostensibly why the agents are in town, at least—connect. After that, a second playthrough on Casual will deliver the story without quite so much running about finding finger print paper, non-rechargeable batteries, a pair of hilariously large wax lips, that sort of thing.

“There are some things in the game that a larger publisher would have probably stood in the way of.” — Ron Gilbert

And it’s a funny story, too—I’d place its chuckles-per-hour count somewhere just above Jazzpunk, although you’ll want to adjust that depending on your adventure game experience and likelihood of getting the more in-joke-y one-liners and items to pick up. (Such as… what’s this? An empty can of tuna heads?)

“There’s a real dearth of humor in games out there, today,” Gilbert says. “I don’t really know why that it. I mean, there are some funny games around. Most of those get their humor from slapstick, whereas a game like The Secret of Monkey Island had a more sophisticated humor about it. The laughs came from the dialogue, the interactions with other people. I think the last game that really made me laugh out loud was The Stanley Parable.”

One quality that Thimbleweed Park and The Stanley Parable share, besides being capable of tickling a rib or two, is that they’re both the products of very small, closely-knit teams. Sandercock talks about putting jokes into an area of the game without any interference from anyone else on the team: “Ron hadn’t been there for a while, came into it and just said, ‘Yep, that’s Jenn.’ To have that kind of freedom and individuality in a game, that’s nurtured by having a small team, it really helps.”

And while games full of attractive idiosyncrasies can and do emerge from big studios backed by bigger publishers, Gilbert is in no doubt that had Thimbleweed Park gone down that avenue of financing, rather than receive its green light through a successful Kickstarter campaign in late 2014, it’d have seen some of its more unique content removed.

“I don’t want to spoil anything, but there are some things in the game that I know a larger publisher would have probably stood in the way of,” he explains. “The game takes some weird detours, that are not a part of the main path, that perhaps a publisher would have shut down. The argument would be that it wouldn’t be worth spending time and money on what was essentially just a joke at the end of the day.

“But a lot of publishers are good, don’t get me wrong. A good publisher will be there to pull you back when you’re about to derail. They’re look over your shoulder and keep you honest. They’ll question your decisions, and not in a bad way. They’re making sure that everything has been properly thought through. I think that’s where a lot of Kickstarters run into problems, because people don’t have the experience to really self-censor, and self-regulate.”

Not that Thimbleweed Park‘s crowdfunding campaign, even when it arrived with someone with Gilbert’s reputation behind it, was a totally pleasant experience.

“The thing I didn’t think about, ahead of launching the Kickstarter, is that people can remove their money.” — Ron Gilbert

“It was white-knuckle terror for the full 30 days,” Gilbert recalls, with a smile that’s still partially formed from relief. “We funded the game on the fourth day, which was relatively quick. But the thing I didn’t think about, ahead of launching the Kickstarter, is that people can remove their money. And I remember the first time I saw that. I was scrolling down the list of pledges and, boom, $25 subtracted. And we had a couple of $10,000 pledges, so I was thinking: what if that’s some kid who’s stolen his parents’ credit card. So you’re worried—what happens if people do start taking their money back?”

As it happened, they didn’t. Thimbleweed Park made a total of $626,000 on Kickstarter. Which sounds a lot, but to Gilbert and team it didn’t represent anything close to a “limitless” figure, with which he could relax and throw money at any problem that came along, with little concern for the bottom line.

“We have nearly unlimited memory, infinite storage, for games now,” Gilbert says. “The original Maniac Mansion was 320k. It was two sides of a single-density floppy disc. And there was a lot of challenge in making that game, because we had a very limited amount of space. It was a constant struggle—we wanted two more rooms, but we couldn’t have them. It got easier with Monkey Island, but we still had these very hard limits. Lucasfilm told me: ‘You have five discs. That is the budget.’

“The thing that I don’t have, today, is infinite money. Money, and time. So those become the limiting factors for Thimbleweed Park. We can have all of these different animations, but there comes a point where we have to have it all done, and we only have so much money to pay the animators, so we have to be careful that we don’t run over on anything.”

The game has run over—look on Kickstarter and you’ll see that its release date was supposed to have been June 2016. As of right now, it’s out “soon.” Gilbert puts at least some of this delay down to his own slight mismanagement of the game’s development.

“Even with 30 years of experience, I still got caught with stuff on this game,” he explains. “The recording of the voices ran way late—I should have had that done four months before it was. If we’d had a publisher, they’d have been telling us to get into the studio and just get it done. It all worked out well in the end, but it was a scramble.

“I was late in getting a bunch of the writing into the game, and we couldn’t record without that—but there was a lot keeping us busy, and I was just swamped. I started to cast the game, but was really unhappy with the quality of actor that we were getting, so I pushed that side of the game back, and back. And suddenly there’s no time left, and this has to happen. Having a really good publisher probably would have solved that.”

With over 15,000 backers to consider, not to mention the many thousands of expectant adventure game nostalgists and newcomers alike who didn’t put their money down in advance, it’s for the best that Thimbleweed Park didn’t rush its way to completion, and that every detail was delivered to a standard expected of its much-experienced makers.

What I’ve played of the game thus far bears that out—it plays and looks like a classic adventure game of the early 1990s. It doesn’t quite sound the same, and no doubt has a more self-referential wit to it, but if the objective was to produce a game that recalled the past without actually duplicating it verbatim, improving what didn’t work so well before, it seems like a success.

Naturally, only playing the whole game will reveal exactly where Thimbleweed Park ranks amongst the adventure greats, if at all. But you’d have to be a real tuna-head to not want the best for it.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Bandai Namco Entertainment Inc. -

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

Collage by VICE -

Screenshot: Mintrocket