Astronomers have glimpsed a galaxy located an unprecedented 13.5 billion light-years from Earth, just 330 million years after the Big Bang, making it by far the most distant object ever seen by humans, according to a pair of new studies.

The stunning galaxy, called HD1, is 100 million light-years farther than the next most distant object ever spotted, and emits a bright ultraviolet glow that currently defies explanation. It was discovered by Yuichi Harikane, an assistant professor at the University of Tokyo, who is the lead author of a study that reports the breakthrough in The Astrophysical Journal on Thursday.

Videos by VICE

A companion study published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters, co-authored by Harikane, said the discovery of HD1 and another galaxy that is slightly closer to Earth, called HD2, has “opened a new window on galaxy formation” and offered “a remarkable laboratory to study the universe.” Indeed, the new discoveries might either provide the first glimpse of the oldest stars or shed light on longstanding questions about the formation of supermassive black holes in the early universe.

“I was very surprised when I found this object, because the color of this object (brightness in each photometric band) matched the expected characteristics of a galaxy 13.5 billion light-years away surprisingly well, giving me little goosebumps,” said Harikane, who is also an honorary research associate at University College London, in an email. He credited his colleague, Akio Inoue, for confirming that HD1 was “an amazing object” and noted that before the new study, scientists hadn’t even found candidates for objects that existed 13.5 billion years ago. Now, with HD1 and HD2, they have two.

Harikane and his colleagues were inspired to probe this ancient epoch by similar studies that have pushed back the observational timeline of the universe. Indeed, the new research appears just a week after an unrelated study announced the discovery of the farthest star ever seen, which was detected by a different method.

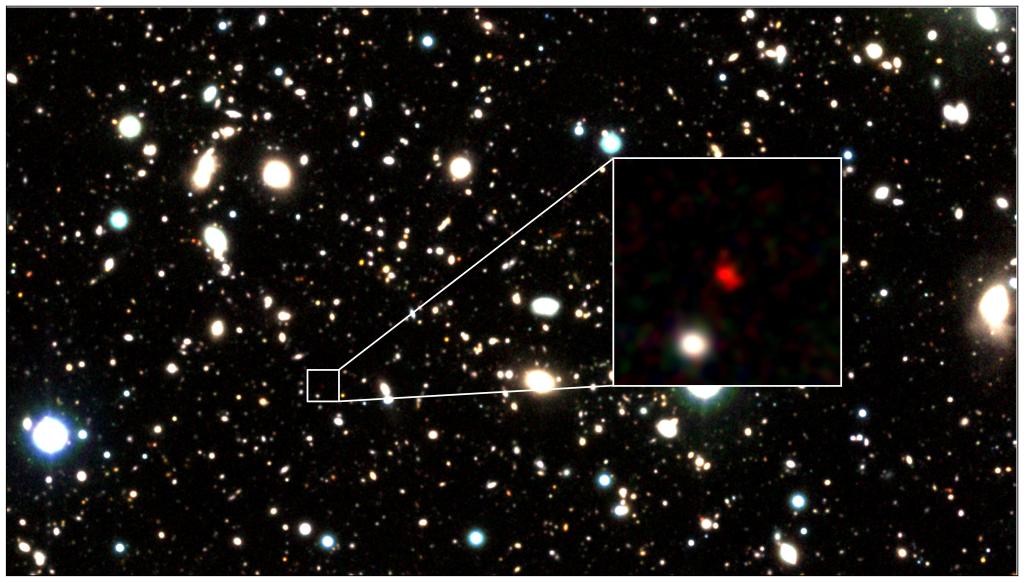

To probe the farthest galaxies ever seen, the researchers studied over 1,200 hours of observations from the Subaru Telescope, VISTA Telescope, the UK Infrared Telescope, and Spitzer Space Telescope. This huge dataset revealed the telltale red glow of the distant galaxies, which is caused by the wavelengths of their light getting stretched as they travel billions of light years across space.

The team then confirmed the discovery of HD1 using the Atacama Large Millimeter/ submillimeter Array (ALMA), one of the world’s most sensitive telescopes. ALMA also revealed insights into the unusual spectrum of the galaxy, which is extremely luminous in ultraviolet light, suggesting that some kind of energetic process is occurring there.

One possible explanation is that HD1 is packed with the first stars ever to shine in the universe, a speculative group known as Population III that has never been seen and is thought to be made entirely of lighter elements such as hydrogen and helium. The ultraviolet glow could also be caused by interactions with a supermassive black hole inside the galaxy, which would provide the perfect opportunity to resolve questions about how these objects grew so immense so quickly in the early universe.

“Both of these two scenarios will have a big impact on studies of galaxy formation and evolution,” Harikane noted. “Population III stars are not found yet. So if HD1 is confirmed to have Population III stars, this will be the first report and give an insight into the formation timescale of Population III stars.”

“If HD1 contains a supermassive black hole, this will be the most distant supermassive black hole confirmed and will be a key to understanding what is the seed of supermassive black holes,” he added.

To that end, Harikane and his colleagues are eager to conduct follow-up observations of the stars with next-generation telescopes, including the James Webb Space Telescope, which was launched in December.

“Spectroscopic observations with James Webb Space Telescope will not only determine the exact distance of HD1, but also distinguish these two scenarios by detecting a strong doubly-ionized helium line made by Population III stars,” Harikane said.

“Observations of these very distant galaxies allow us to understand when and how the first galaxies form,” he concluded. “Confirming these very distant galaxies directly constrains the formation timescale of galaxies in the early universe, and investigating physical properties (e.g., Population III stars, a supermassive black hole) improves our understanding of how these galaxies form.”