Above Sigmund Freud’s couch, 40 x 50″ archival pigment print, 2008. Photos by Jason Lazarus

This short story appears in the August Issue of VICE Magazine

Thomas was furious with his shrink and finally found the courage to tell her so. Three weeks without analysis over the long Christmas break had given him the chance to get his head together.

Videos by VICE

“The fact is,” he began, “if it hadn’t been for you I wouldn’t have left my wife. I would still have a home and family and an identity that made sense to me. Not to mention the financial side of it all.”

Made worse, of course, he might have added, by these £90-an-hour sessions.

His shrink was a small squat woman in her mid 70s who shuffled around a stone floor on slippers while smoking ultrathin menthol cigarettes. She had never asked Thomas’s leave to smoke during his visits, which—given that this was theoretically a place of work—was quite possibly illegal, he reflected, and certainly disrespectful. On the other hand he hadn’t asked her not to smoke. She exercised a strange power over him that Thomas was beginning to find rather irksome.

The shrink got up to look for a shawl. She must have been cold. Now she sat again and tapped away a little ash. As she looked up, her raised eyebrows seemed to say, Go on, then.

“I came to you in a dilemma over my marriage; you took the decision for me after only two or three meetings. From everything that’s emerged in our conversations since, and that’s nearly eighteen months’ worth, it’s become clear that you are viscerally opposed to marriage in general, above all long marriages. No doubt you tell all your clients to leave their husbands or wives. Basically my whole life has been radically and negatively transformed just because in a moment of weakness I took a friend’s advice and came to the wrong shrink.”

The shrink drew on her cigarette and pulled the brown shawl tight around her shoulders.

“How was your Christmas, Mr. Paige?” she asked. “And New Year’s. Did you go away?”

“No. I was here in town. My girlfriend went back to her family. In Dublin.”

The shrink waited.

“In the end I took advantage of the situation to get a lot of work squared away so there’ll be more free time when she gets back.”

Again the shrink did not speak. When Thomas did not continue she simply settled back in her chair as if to make herself comfortable for a long wait. She appeared, Thomas thought, to be observing him carefully, even sympathetically; on the other hand he had long since realized this must be any shrink’s default setting. Well, he wasn’t going to oblige, he decided. He could stay silent as long as she could. Already he was thinking that at the end of this hour he would very likely discontinue their relationship. But as soon as his posture began to assume a hint of defiance, she enquired:

“Was this the first Christmas you’ve spent away from your family?”

Thomas reflected: “The second.”

Again she made her encouraging face; again he hesitated; again as soon as it seemed he might stay defiantly mute she had a question ready.

“What stopped you from getting in the car and driving over there?”

Thomas too was in an armchair, still in his overcoat. It wasn’t clear to him whether the question came from genuine interest or a desire to provoke; he decided to take it for the latter.

“That would have been a big decision,” he said, “precisely thanks to all the drastic steps I’ve taken this year.”

He didn’t say “under your influence,” but felt he could trust her to read the accusation in his voice.

The shrink grinned and sucked the last wisdom from her cigarette. She leaned forward and stubbed it out carefully. The ashtray was clean because, as Thomas had noted some time ago, she always emptied the ashtray between clients and opened the window for a few minutes, which was perhaps why she had felt cold. Outside it was raining on slushy snow.

She waited.

“I feel if my wife were ever to find out the kind of advice you’ve been giving me, she’d take you to court for destroying our marriage.”

“It would hardly have been fair on Elsa,” Thomas added, almost involuntarily. It annoyed him that he tended to throw more into the conversation than was perhaps necessary. Sometimes the whole hour was pretty much his own monologue. Which was rather letting her off the hook, he thought. His motor mouth making her money for her. On the other hand he was there to be analyzed, not to keep things hidden. In the end, the whole quandary boiled down to the question, was she friend or foe? And if foe, why on Earth was he paying her to fight him? Suddenly he felt he must solve this question today.

“Sometimes,” he announced, “I feel if my wife were ever to find out the kind of advice you’ve been giving me, she’d take you to court for destroying our marriage.”

The shrink did at least seem very attentive now, fascinated even, which was gratifying.

Thomas waited. He would decide this very day if it made any sense at all going on with this farce.

“Tell me about Christmas in the family,” the shrink said.

Thomas sighed.

“I always wanted a traditional English Christmas,” he told her.

She made her encouraging face.

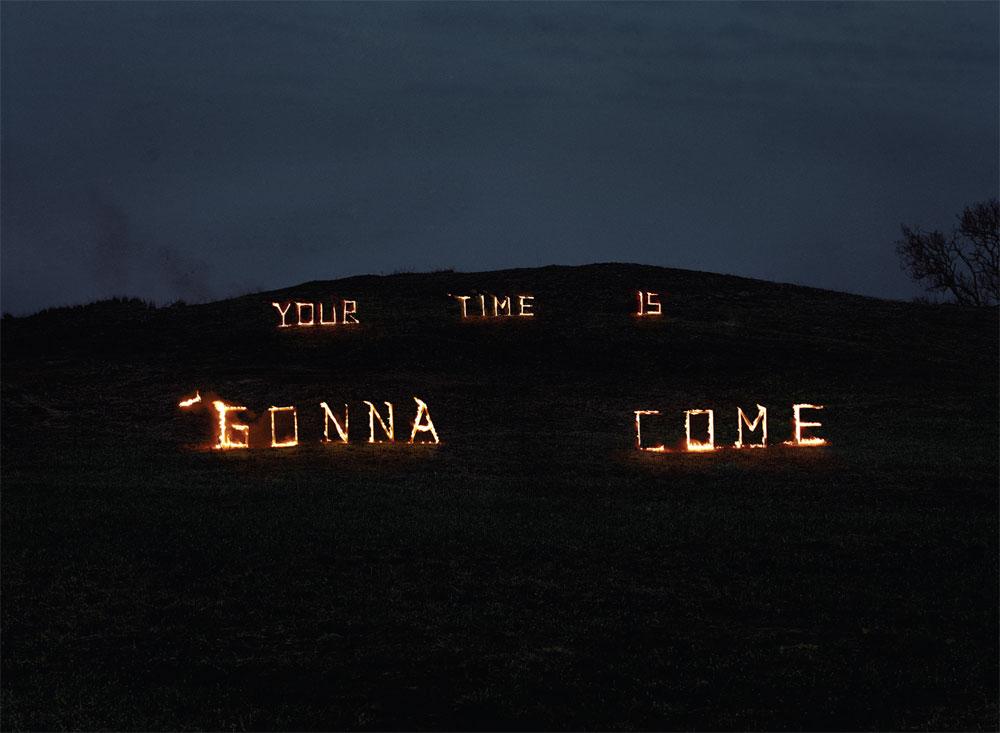

Untitled, 40 x 50″ archival pigment print, 2011

“I mean having a tree. As big as possible. With fairy lights. A turkey lunch. Plum pudding. Exchanging presents on Christmas Day itself. Seeing them under the tree on the days beforehand. We used to have lunch, which was pretty heavy, with quite a lot of wine, something special and expensive, open our presents together sitting around a fire, then collapse into bed or go for a walk.”

“Sounds idyllic,” the shrink laughed. “I can’t see why you didn’t drive home then.”

Thomas felt angry.

“Obviously it wasn’t quite like that. Or it was like that, but it didn’t feel as it should have felt. Or as I always hoped it would feel.”

The shrink proffered her questioning, knitted-brow look. Sometimes it seemed she worked more with facial expressions than with words.

Thomas tried to focus on Christmas. For some reason he found himself saying, “The Ghost of Christmas Past.”

The shrink ignored the allusion.

“Actually it was all very tense. First, Mary didn’t want the tree because it dirtied the floor with its needles. She didn’t want the turkey because she didn’t feel like cooking it. She didn’t want to wait for Christmas Day to exchange presents because why not use things once they’d been bought? Probably she was right and it was stupid of me to insist. I think she thought we were doing things too much the way my family had always done them, while her family had never really had a Christmas tradition. It didn’t seem they really did anything at all on Christmas. The children loved it, of course. When I said, ‘OK, I give in, not this year then,’ they started clamoring for the tree and the turkey and so on, and then she changed her mind and we did it anyway, but with a feeling it had all been an immense effort to get to that decision.”

The shrink nodded.

“Probably it was my fault. Probably I shouldn’t have suggested anything at all.”

The shrink pulled out a face that seemed to mean, How depressing, but there you go.

“Then it would have been up to her to suggest what to do, and she would have felt more in control and positive about it all.”

The shrink frowned. “Your wife wasn’t working at this point?”

“Freelance jobs. Every now and then.”

The shrink waited.

“I remember one time she called in the decorators between Christmas and New Year’s.”

Here the shrink raised her eyebrows as one both surprised and amused. It was the most spontaneous of her expressions so far.

“Tell me,” she said, feeling down the side of her armchair for her cigarettes. Thomas was aware of a sudden reciprocal warmth between them. He was rather good at telling stories, and she was an attentive listener. He tried to remember.

“I had invited my mother over that year. Or rather, we had invited her. I would never have invited my mother for Christmas, or anyone else for that matter, if Mary hadn’t agreed. Maybe it was even she who suggested it. I can’t remember. Actually, they got on pretty well. On the surface, at least. Mary was generous with guests, she put on a big show for them, but then she’d get impatient, especially if the stay was extended. As if put upon. Like they had invited themselves. It was also the first year of the dog. He was still a puppy.”

“Ricky,” the shrink said.

“The fact is, over the next few days I felt so angry I wanted to die. I really wanted to lie down and die.”

Thomas smiled. If there was one aspect of the shrink’s performance you couldn’t fault her on, it was her memory. Gradually she was becoming a repository of his entire life. Often he wondered how she could do that for all her clients, the same way he wondered how pianists could recall all the pieces they played. No doubt it was this that gave her a hold on him.

“That’s right. Ricky.”

“The trophy dog,” the shrink added. She was rubbing it in, but he could hardly deny these had been his words.

“That wasn’t a problem,” he said quickly, “since my mother always loved dogs. We always had one when I was a kid.”

The shrink waited.

“Anyway, the house needed redecorating. Or rather, the walls needed repapering. My wife liked them to be smart and fresh.

I wasn’t too concerned myself. Probably I’m a bit lax that way. I think men and women differ over stuff like that. She had waited till the children were pretty much grown up and had stopped putting fingerprints on the wall. Anyway, she managed to get a cheap price from a couple of guys who worked for a decorating firm. They would do it over Christmas with the firm’s equipment, but moonlighting and paid under the table.”

Thomas cast about for the actual sums of money but couldn’t remember. “Anyway, it was pretty cheap. I mean, it was a serious saving. Mary was always very smart that way.”

“Except it was Christmas.”

“Right. And my mother was staying. She wasn’t well, either. I think she’d had her first operation that year.”

The shrink nodded. “Presumably you objected to bringing the decorators in.”

“I wasn’t enthusiastic. I felt we should do it in summer when it wouldn’t matter having the windows open, and the hell with the money since we didn’t really have a money problem at the time. I think Mary was naturally a little anxious over money at this point. Not sure why. She didn’t use to be when we were younger. Then it was the other way around. Me worried, her not. Anyway, she called them in. I think it was the day after Boxing Day. If not Boxing Day itself.”

“So,” the shrink observed. “You were insisting on a traditional Christmas show for your mother, and your wife got the decorators in.”

“Actually, Mary liked cooking turkey. I mean, once she’d decided to do it. Having my mother there gave her a chance to show how good she was. And she really was. Really is. Certainly much more elaborate than Mum ever could be. Mary is a great cook. In fact, from the moment we agreed it would be right to have Mum over, because it might well be the last year she would be well enough to make the trip, I can’t recall any of the usual argument about whether we should have a traditional Christmas lunch or not.”

The shrink waited.

Thomas sighed. How weird, suddenly to be going over all this old stuff again. He felt torn.

End of summer lover (the plant on her windowsill), 16 x 20″ archival pigment print, 2008

“Basically, it was a disaster. My wife was still in the phase when she thought the dog needed a two-hour walk every day. I mean, she had got herself an outdoor kind of dog, and she felt guilty if she didn’t walk him enough.”

“Guilty?”

“She said he needed to be walked. She had a responsibility. Obviously my mum couldn’t go with her, because she was pretty much reduced to a few steps around the garden at this point. That meant I had to stay at home. So Mary would take Mark for company. Of course, he would rather have slept in. Mary would bribe him by taking him to the coffee bar for breakfast, but then he had to walk for two hours and came back irritated and annoyed. Even the dog was exhausted.”

“And your daughter? Presumably she was home for Christmas.”

Thomas laughed more heartily. “Sally? She wouldn’t have dreamed of going. She just says no. Refuses point blank.”

The shrink smiled. “There’s always someone who does that.”

Thomas stopped and breathed deeply. What was that supposed to mean?

“I was on her side,” he said, as if this altered anything. “She was studying pretty hard for his finals at that point. To make matters worse, if I remember rightly, Mark’s girlfriend had left him on Christmas Eve, the same day Mum arrived, which rather put a damper on the Christmas lunch. He was really upset. That was his first serious girlfriend. Of course, we were being as sympathetic as possible, but no doubt he could see that we were all pleased as well because it was pretty obvious to everyone that they weren’t suited to each other.”

“Ah,” the shrink nodded, sagely.

“In fact, as I recall it, I was thinking this was a major piece of good news, them splitting up. You know one’s always terrified of one’s children choosing the wrong partner, right? Mary and I were a hundred percent agreed about that, the girlfriend, though, as I say, the breakup put a very big damper on things; Mark is usually a lot of of fun, and seeing him take it so hard and then texting all the time wasn’t encouraging. Plus of course there was the worry they would get back together. At which things would have been worse than before.”

The shrink raised a very wry eyebrow here, which again seemed to be trying to tell Thomas something. His mood had definitely shifted. It felt good to be telling the story of this awful Christmas, though dangerous as well, exhilaratingly dangerous. Like walking along the edge of a cliff or something. Suddenly there was a rush of memory.

“The fact is, over the next few days I felt so angry I wanted to die. I really wanted to lie down and die.”

In response to this the shrink sat up with a face of intense concern. It was almost comical. Sometimes Thomas thought of her as Yoda in Star Wars. There was the same mix of exaggerated facial expression and supposed wisdom. “Imagine Yoda smoking ultrathin menthol cigarettes and you have it,” he had once told Elsa, but then it turned out she hadn’t seen Star Wars. She hadn’t been born at the time.

“People who feel angry often want to hit back,” the shrink pointed out, “but not to die.”

Thomas hesitated. Was he really going to go there?

“Normally,” he stalled, “I would have joined in the walks, even with my mum being there—I like walking—but somebody needed to stay home and be around while these guys did the decorating. There was lots of heavy furniture to move and cover up. That’s it, I remember now. It was part of the cheap deal she’d negotiated that they would find each room ready to paint or paper when they arrived in the mornings, without having to do all the preliminaries. And I knew if I didn’t cover things up properly, masking tape around the skirting board and so on, so they got paint drippings on them, or if the rooms weren’t ready, there would be trouble. I was tired that year and not feeling too well at the time. Whatever. I don’t want to go into that. It was an old problem I’d been having.

But what drove me mad was these two guys, and we’re talking your classic working-class decorators, one middle-aged, one young, a real double act, they could see perfectly well what the situation was between myself and Mary, and they were faking respect for me but actually smirking, and my mother could see this as well and the children too, and the guys would ask me questions, what to do about this corner or that mirror, and when I answered they said maybe I should phone the missus in case she sees it differently, and they were right of course, so I did, and she asked me to pass the phone to them so she could speak to them directly, and I realized they had only asked me first to save themselves the cost of the phone call, because they could perfectly well have phoned her directly and left me to get on with whatever I was doing, and then right in the middle of it all, the day they were going to do the big bedroom, our bedroom, I made a mistake and put everything but the bed out on the terrace—the bedroom was on the top floor and had a kind of roof terrace—the bedside tables, an armchair, the carpets, the lamps, a chest of drawers, a low table, etc., etc., and then a little later when I was downstairs making a coffee for Mum—one problem was we couldn’t put the heating on because of the need to keep the windows open, so it was freezing, except in the kitchen where I’d fixed a space heater—the day suddenly clouded over and this huge, but really huge gust of wind, completely anomalous, came along and blew everything about, including a nice lampstand with a madly expensive Venetian-glass shade that shattered into about ten million pieces over the chairs and rugs, and the decorators pretended to be sympathetic but were really sniggering.

So then for the rest of the morning I was dreading my wife coming back, which she eventually did with the dog looking more knackered than ever and Mark in a state of angry misery, and Mary sighed as if to say what could one expect, and she said maybe this was a good moment to get rid of the big painting above the stairs that was a favorite of mine but that she had never liked. I should take it to my office, she said, where she knew there wasn’t a wall big enough for it. My mother, needless to say, was looking like all she wanted to do was to be allowed to get on the next train home and die in peace, she wasn’t used to people arguing, and…”

Untitled, 26 x 36″ archival pigment print, 2008

Thomas stopped. The shrink had been chuckling but now used a drag on her cigarette to change the expression to a frown. Thomas knew then that she knew he wasn’t telling her the half of it. He felt cautious.

“I remember having a dream,” he began. “One of those nights.” Again he stopped.

The shrink watched. For the first time she seemed skeptical.

“I’m not sure if it was really one of those nights. But it comes back to me now.”

The shrink sighed. “Tell me.”

“I had a girlfriend at the time,” Thomas said, a little sheepishly. “A mistress, maybe you’d have to say.”

The shrink was not surprised. They had been through this.

“Let’s say a girlfriend,” she said.

Thomas thought, I’m paying her to nod like this.

“I’d been with her quite a while at this point. We got on pretty well. Anyway, I dreamed we were in a mountain valley. It was green and very beautiful, and we seemed happy and relaxed, and she was dressed very beautifully and rather chastely in a long, flowery skirt down to bare feet. I think my feet were bare too. I almost always have bare feet in dreams. Go figure.”

The shrink nodded.

Thomas thought, I’m paying her to nod like this.

“It was beautiful, I mean the whole scene just said: beauty, serenity, happiness. A caricature. Except there was the problem that we needed to go somewhere to eat and sleep. There was nothing in the valley but beauty. You couldn’t eat that. So we were following a path downward that seemed to be taking us somewhere, except that at a certain point it led into a tunnel. It seemed to be an old railway tunnel, disused now, and we started walking into it, thinking we would soon be out. It was pitch dark, which was worrying with us being barefoot, but there was something faintly white in the distance, and we thought it must be daylight, even if it didn’t look like daylight, in fact when we got there it was ice, or maybe frozen snow, blocking the tunnel from top to bottom, there was no way through, it was packed tight, and I remember waking and thinking how strange it was that there could be snow inside a tunnel when there was none outside and wondering how it had got there.”

Thomas stopped.

The shrink stubbed out her second cigarette and smoothed out her dress, which had rumpled when she leaned forward.

“You were telling me about that Christmas.”

“I drove my mother into town to the station, probably New Year’s Eve, pretending it had been a great stay and that everything was fine, even though each of us knew perfectly well that the other knew perfectly well that on the contrary nothing was fine, everything was wrong. And driving back from the airport I thought for the thousandth time that my wife was behaving the way she was because of my mistress, not that she knew about her, but I suppose these things are sort of in the air, so I called her, my girlfriend—I stopped in a service station, I remember—and told her we would have to stop, it was over. She was terribly upset, couldn’t believe it even, because we had been getting on so well, and naturally I felt a complete shit, not to mention spectacularly unhappy, but also like I had no right to complain, since it was hardly fair of me to have this mistress, on either of them, I mean, Mary or her, and when I got back the dog had wagged his muddy tail all over the fresh paint to one side of the front door and Mary was just laughing and I couldn’t understand why she wasn’t angry. I suggested we go out to a celebratory dinner for New Year’s Eve, but she said the dog couldn’t be left alone because the fireworks would drive him mad and the children couldn’t dog-sit because they both had parties of their own, at one of which, needless to say, Mark got back with his inappropriate girlfriend. So all those tears had been for nothing, and on the day…”

“Mr. Paige.”

Thomas stopped.

“I’m afraid our time is up, and I have another appointment.”

The shrink smiled kindly, but somehow sadly too.

“Let me just ask you, though, was this Christmas you’ve just spent on your own better or worse than that?”

Thomas had already moved forward on his chair to get up. He felt foolish.

“Well,” he grinned, “people kept commiserating because I was alone, like, ‘How awful, Christmas on your own,’ you know, but actually, well, actually, it was fine. I felt fine.”

“And your girlfriend is coming back soon?”

“This evening. I’m going straight to the station right now to meet her.”

Saying this, he was embarrassed he was so unable to hide his pleasure and, yes, his pride.

The shrink stood up, smoothed her crumpled dress, picked up the ashtray with her left hand, and offered her right to Thomas to be shaken.

“Next Thursday, then. Same time. Do feel free to call me if you need to.”

In the hallway, Thomas passed a man who was struggling to pull off a motorcycle helmet. During the bus ride to the station, watching sprays of slush from the filthy gutters, he reflected on the shrink’s method. Was it a method? He felt ashamed of himself and rather happy.

More

From VICE

-

(Photo by Elena Danileiko / Getty Images) -

A Kansas City Chiefs fan dresses as Santa Claus during an NFL game between the Houston Texans and Kansas City Chiefs on December 21, 2024 at GEHA Field at Arrowhead Stadium in Kansas City, MO. (Photo by Scott Winters/Icon Sportswire via Getty Images) -

Prisoners at HMP Five Wells. Photo: Joe Giddens/PA Images via Getty Images -

Collage by VICE